MENTORING

Beyond offering academic help, a handful of universities are finding ways to support minority students on an emotional and community level, with the goal of outlining paths toward technical and academic careers.

Christopher Smith, a doctoral student in biomedical engineering, looks at stem cell samples through an inverted microscope in a lab at the Johns Hopkins University medical campus in Baltimore in 2011. Despite robust hiring in the fields of science, technology, engineering and math, the percentage of African-Americans entering such careers has fallen during the past decade. (Patrick Semansky/AP/File )

By Schuyler Velasco

Christian Science Monitor, October 26, 2016 —For Stacey LaMar Houston, a sociology doctoral student at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, a sense of being an outsider comes not just from the fact that he looks nothing like his peers, but also from having vastly different life experiences.

“There aren’t many black males in my program,” he says. “I was the only doctoral student there.”

“But I also have a 2-½ year old,” he adds. “It’s a shock for everyone else. I don’t have anyone to talk to about what it’s like to be raising a child.”

Though there are black, male professors in his department, they mostly couldn’t identify with his background of growing up poor, or juggling the intense demands of graduate study and family life.

“When I admitted to one of my professors that I was going to be having a baby it was kind of like, ‘Oh, not another one, not a young black male with a kid,’ ” he says.

Mr. Houston is happy with graduate school on the whole, despite those various points of isolation. But other students with outsider status – from women in hard sciences to black men in liberal arts programs – have come to the conclusion that their fields of study aren’t good long-term fits. Despite increasing college enrollment by African-American and Latino students, their numbers in graduate programs remain disproportionately low.

For example, African-American students received just 4.5 percent of doctorates in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM), according to the National Center for Education Studies.

“There’s extra labor being a person of color or a woman in a field where you are already constantly proving yourself,” says Ebony McGee, an assistant professor of diversity and urban schooling at Vanderbilt. “The thought of dealing with that for six or seven years is daunting.”

Prof. McGee is one of a handful of academic leaders across the country who are tackling the issue of treating those experiences of “otherness” as a challenge as important as getting enough study time. Their solutions are multifaceted: monitoring racial and gender dynamics within departments and lab groups and offering emotional support resources to minority students. But they are also expanding opportunities for these students to connect with mentors – professors, business leaders, and more senior peers – with similar backgrounds and experiences.

“Having a community that says, ‘You are us,’ and having affinity groups that remind people how they are part of that broader community can be helpful, and lead to more opportunities to connect,” says Renetta Garrison Tull, the associate vice provost for graduate student development and post doctoral affairs at the University of Maryland Baltimore County.

The ‘numbers guy’

Houston found the community and mentorship he was looking for far away from the sociology department, by way of a job posting in McGee’s lab at Vanderbilt’s engineering school.

McGee studies the experiences of minority PhD students in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) fields, in particular why they are so underrepresented in related academic career tracks. Black professors make up just 2.5 percent of engineering faculty, for example, a proportion that hasn’t budged for several years. The research piqued Houston’s interest as a sociologist, and he became the “numbers guy” on her team, helping to collect, analyze, and present quantitative survey data.

“Some of my own experiences were mixed up in there, and it was cool to see that I could contribute to that,” he says. “She’s a newer professor so it helped me, watching her navigate academia the way she has, both through observations and her giving me tips.”

McGee also leads a mentoring initiative that brings scholars from all over the country to Vanderbilt share research and talk about their academic journeys.

“I’ve been able to connect with specific professors on having a toddler, and others on the financial situation … coming from nothing and then being in this weird status where you are elite, but the income does not yet match that,” unlike students from middle or upper class backgrounds who can fall back on family support during the lean grad-school years, Houston says.

Role models, obviously, can be scarce for underrepresented groups, so programs like Vanderbilt’s, as well as a wide-ranging mentorship initiative at the University of Maryland Baltimore County, are casting a wider net.

McGee also leads a mentoring initiative that brings scholars from all over the country to Vanderbilt share research and talk about their academic journeys.

“I’ve been able to connect with specific professors on having a toddler, and others on the financial situation … coming from nothing and then being in this weird status where you are elite, but the income does not yet match that,” unlike students from middle or upper class backgrounds who can fall back on family support during the lean grad-school years, Houston says.

Role models, obviously, can be scarce for underrepresented groups, so programs like Vanderbilt’s, as well as a wide-ranging mentorship initiative at the University of Maryland Baltimore County, are casting a wider net.

UMBC hosts an annual Summer Success Institute, a retreat that invites faculty from other universities in the US and overseas to serve as “mentors in residence” for graduate students across the Maryland university system.

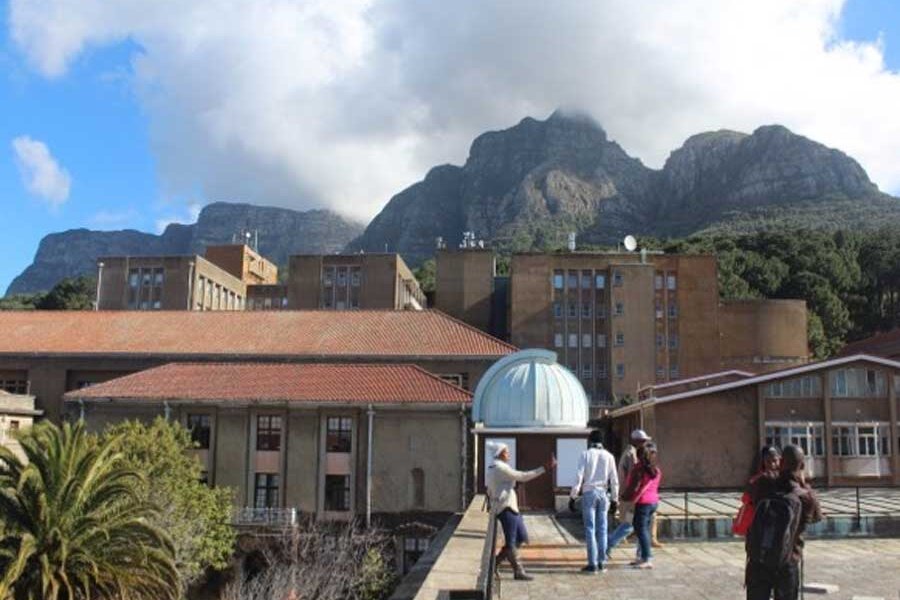

Students in the National Astrophysics and Space Science (NASSP) winter school stand in front of a telescope at the University of Cape Town on June 27, 2016. Each year, a group of physics students from South Africa’s historically black universities are invited to spend two weeks at the university completing an astronomy crash course meant to prepare them for further study in the field. (Ryan Lenora Brown )

LISTEN: EqualEd: Professor Medupe’s Story, one of the first black South Africans to get a Ph.D. in astrophysics.

The program, Dr. Tull says, has become a career pipeline for many participants, with some mentors eventually helping hire student participants at their own universities. In other cases, mentors have brought their own students to the retreat and they then wind up working for the University of Maryland in some capacity.

“In many cases, students have never had a faculty member who looked like them and engaged them outside the classroom,” Tull says. “They keep in touch, and come back to give each other updates the next year. It’s a way for the students to discuss issues they may be having and not feel alone.”

Combating that sense of isolation, as well as validating feelings of being shut out, is a crucial piece of the puzzle when it comes to boosting the numbers of underrepresented groups, experts say.

How much merit in meritocracies?

Doing so can be a particular challenge in highly technical STEM fields with a deeply ingrained sense of meritocracy. Since 2003, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Prof. Susan Silbey has led an ongoing survey of women engineering students at four colleges, aiming to figure out why they drop the career in such high percentages.

For example, an estimated 40 percent of women who earn engineering degrees – a profession in which they make up just 13 percent of those employed in the field – either quit early on or never enter the field at all.

Through diaries and interviews, female students consistently reported getting “shunted aside” by male students and relegated to nontechnical roles in group projects.

Additionally, compared with those in other careers, engineering students were more conditioned to attribute such treatment to personal shortcomings, rather than structural ones. Many of Prof. Silbey’s study subjects “don’t identify as feminists, because they say it is claiming being special,” she says. “They believe that all people are equal and the system works to reward excellence. Doctors and lawyers [professions with higher numbers of women], they know the system is different. Women students absorb the engineering way and they apply it to themselves. They want to be treated objectively.”

The students that McGee at Vanderbilt and Tull at UMBC work with want to be treated objectively as well, they say, and their programs focus on doing just that, while making sure that these students have the emotional and community support they need to thrive.

UMBC is also part of a larger initiative within the University System of Maryland to increase minority professorship. Called PROF-it, the program partners with community colleges to give doctoral and post-doc candidates hands-on teaching experience, and offers workshops on how to be an effective professor.

“There’s a reward in that shared social connection, acknowledging that you are connected and valued,” Tull says.