By

NBC News Latino, May 18, 2017 —

In the nearly half century since the landmark Supreme Court decision Loving v. Virginia made it possible for couples of different races and ethnicities to marry, such unions have increased fivefold among newlyweds, according to a new report, “Intermarriage in the U.S. 50 Years After Loving v. Virginia.”

In 2015, 17 percent, or one in six newlyweds, had a spouse of a different race or ethnicity compared with only 3 percent in 1967, according to a Pew Research Center report released Thursday.

“More broadly, one-in-10 married people in 2015 — not just those who recently married — had a spouse of a different race or ethnicity. This translates into 11 million people who were intermarried,” the report states.

This June 12 marks the 50th anniversary of Loving v. Virginia, the landmark Supreme Court decision which overturned bans on interracial marriage. The story of the case’s plaintiffs, Richard and Mildred Loving, was recently told in the 2016 movie “Loving.”

Latinos and Asians are the most likely groups to intermarry in the U.S., with 39 percent of U.S.-born Hispanic newlyweds and 46 percent of Asian newlyweds marrying a spouse of a different race or ethnicity. The rates were lower with foreign born newlyweds included, 29 percent for Asians and 27 percent for Hispanics.

The largest share of intermarried couples — 42 percent — include one Latino and one white spouse, though that number has declined from 1980, when 56 percent of all intermarried couples included one white and one Hispanic person.

The most significant increase in intermarriage is among black newlyweds; the share of blacks marrying outside their race or ethnicity has tripled from 5 percent to 18 percent since 1980.

There are gender differences though, when it comes to intermarriage among certain groups. Male black newlyweds are twice as likely to marry outside their race or ethnicity than black women (24 percent to 12 percent). Among Asian Americans, it’s the opposite; more than a third (36 percent) of newly married Asian women had spouses of a different race or ethnicity compared to 21 percent of newly married Asian men. Education also played a role. There has been a dramatic decline in intermarriage among Asian newlyweds 25 and older who have a high school education or less, from 36 percent to 26 percent during the years from 1980 to 2015.

While white newlyweds have seen a surge of intermarriage, with rates rising from 4 to 11 percent, they are the least likely of all major racial or ethnic groups to intermarry.

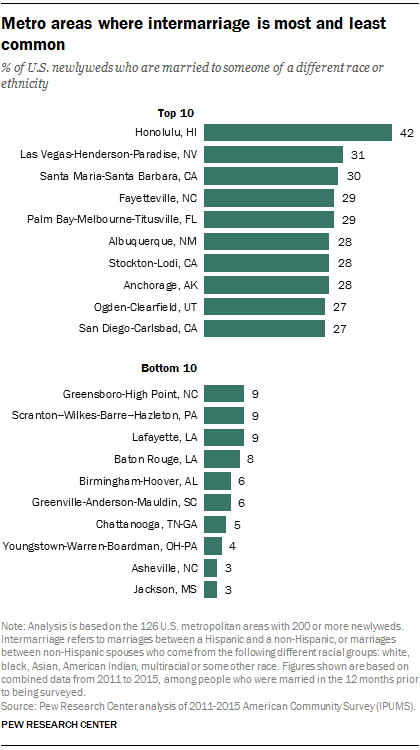

People who are married to a person of a different race tend to live in metropolitan areas. Honolulu has the highest share of intermarried couples at 42 percent.

“We’re a very multicultural family”

Danielle Karczewski, a black Puerto Rican woman, met her Polish-born husband, Adam, when they were interns at a law firm. They’ve now been together for 12 years, and married for six.

“I don’t know if we’re just extremely blessed, but we’ve gotten nothing but tons of support from friends and family,” Danielle Karczewski, 34, of Rockaway, New Jersey, told NBC News.

Adam and Danielle Karczewski pose for a photo in Ortley Beach, N.J. in 2016. Photo credit: Delilah Magao

“We’re a very multicultural family,” she said, adding that her mother-in-law is married to an Indian man and their Polish friend has a black Cuban husband. “We have a Polish version of Noche Buena (Christmas Eve) where my mother-law will cook Indian food — we’ve managed to maintain our individual cultures while celebrating each other’s.”

Growing up with a black father and white mother did not seem unusual to Emily Moss, 24. In fact, her parents’ 12-year age gap was more often a topic of conversation. She bonded with her boyfriend, Ross Bauer, who is of Polish and German descent, over the fact that the two of them had older fathers. But Moss, who lives in New Haven, Connecticut, said being biracial has shaped her politics, particularly on the issue of same-sex marriage.

Claire, Kathleen, Richard and Emily Moss pictured during Christmas 2015. Photo credit: Emily Moss

“Allowing people to marry whomever they love seemed so obvious to me, and I think some of that comes from knowing that my parents’ marriage was illegal once too and how that wasn’t based in anything but fear and prejudice,” Moss said.

But other couples say their union was startling to those in their circles, at least when they first got together.

Toni Callas met her future husband Peter in the early 1990’s when they were both working at The Times of Trenton, in Central New Jersey. It took three years for them to go on a date. When they met each others’ families, their parents were surprised by their relationship; Toni is African American and Peter was third-generation Greek American; he died in 2014.

“Neither of us ever brought home anyone outside our race,” Callas said. While their families eventually embraced the couple, who married in 2001, it was sometimes a challenge to be seen together when they were out in public.

“People wouldn’t say anything to us, but I’d sometimes notice people staring at us. As time went on, I stopped letting it bother me — it wasn’t my job to manage their ‘isms,’ whether that’s racism or whatever,” Callas said.

According to the Pew study, a growing share of Americans say that marriages of people of different races is a good thing and those who would oppose the unions is dropping.

A change in attitudes?

Brigham Young University sociology professor Ryan Gabriel has studied mixed-race couples; he himself is of mixed race. Gabriel said it’s difficult to predict how these couples and their multiracial children may shape the socio-cultural and political landscape in the future. But he said people who are married to someone of a different race tend to be more progressive in their politics and more empathetic overall.

For example, if a person who is white is married to a person who is of Asian, African-American or Hispanic descent, and their children are mixed, the white person may be inclined to fight for racial justice because their family is now mixed, Gabriel said.

“You might spend the holidays together with nonwhite individuals who are now a part of your family. It gives someone the opportunity to see a person of a different race as a complete human being outside of stereotypes they may have had in the past,” Gabriel said. “It helps people realize that race is more a social construct than an actual reality.”

Austin Klemmer poses with Huyen Nguyen after he proposed to her in November 2015 in Hanoi, Vietnam. The couple married in a civil ceremony in 2016. Photo credit: Austin Klemmer

For Denver-based Austin Klemmer, 27, and his Vietnamese-born wife, Huyen Nguyen, 30, it’s culture, not race, that has played a major part in their relationship since they met in Hanoi more than four years ago.

“We do our best to stay attuned to each other’s cultural standards,” said Klemmer. “For example, I always make sure to serve her grandmother first, since you have to respect the level of hierarchy.”

Forty-year-old John B. Georges met his future wife Mythily Kamath Georges, 39, online in 2014. They married in 2015 and had a son in 2016. Georges was born and raised in Brooklyn and his family is Haitian. Kamath Georges was born in India and raised in the suburbs of Cleveland, Ohio.

John B.Georges and his wife Mythily Kamath Georges married in 2015. Photo credit: John B. Georges

“I dated a variety of people of different races. … It’s not who you are, ethnicity wise. It’s not the color of your skin. When you meet someone you have to decide: do they care about me for me or for what I appear to be,” Georges said.

When the Brooklyn-based couple married, they melded both their religious traditions, with a Jesuit priest presiding over the ceremony while Kamath Georges’ parents recited Sanskrit verses. They’re now ensuring their son grows up embracing both his cultures. Kamath Georges’ parents speak to the toddler in Konkani, a language spoken in the South western coast of India, and Kamath Georges encourages her husband to speak Creole to their son as well.

“We want him to understand the cultures that we both come from and the spiritual aspects of our faiths,” Kamath Georges said. “We’re forging our own way, taking the good and leaving the bad.”