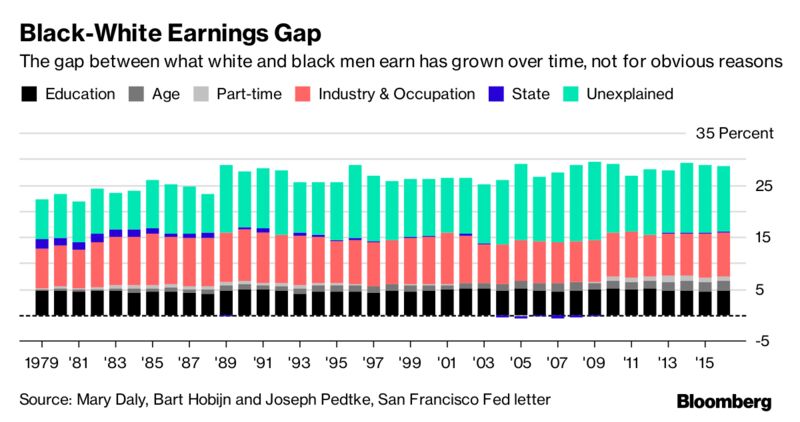

Black workers earn less than their white counterparts in a worsening trend that holds even after accounting for differences in age, education, job type and geography, new Federal Reserve research shows.

In 1979, the average black man in America earned 80 percent as much per hour as the average white man. By 2016, that shortfall had worsened to 70 percent, according to research from the San Francisco Fed, which found the divide had also widened for black women.

A worker assembles Black & Decker Inc. DeWalt brand power drills on the factory floor of the company’s production plant in Charlotte, North Carolina in Aug. 9. (Photo: Luke Sharrett /Bloomberg)

“Especially troubling is the growing unexplained portion of the divergence in earnings for blacks relative to whites,” San Francisco Fed Research Director Mary Daly and her fellow authors wrote in the report, adding that this could owe to hard-to-measure factors including discrimination or school-quality differences.

“The opportunity to succeed is at the foundation of our dynamic economy. In this context, large and persistent shortfalls for African-Americans, or any other group, are troubling,” they wrote.

The San Francisco Fed’s study marks a growing focus by the U.S. central bank on inequality and the lagging employment performance of U.S. minorities. Chair Janet Yellen has talked about the subject and the Philadelphia and Minneapolis Feds have set up institutes to study inequality and social mobility. The increased attention stands in contrast to the past, when the topic was rarely investigated by Fed research staff or broached by officials, who viewed the problem as outside their remit for monetary policy.

The new research, which highlights the persistence of a racial wage gap 50 years after the passage of the U.S.’s landmark anti-discrimination Civil Rights Act, points to a problem for politicians and policy makers: It’s tough to address disparities if it’s impossible to measure what’s driving them.

The fact that the gap has lingered and even worsened over time also means that a stronger labor market, which politicians often cite as a remedy for black workers’ economic disadvantage, probably won’t permanently narrow the divide.

“A job is the first condition, but it’s really not a sufficient condition to fix disparities,” Daly said.

Black workers have consistently higher unemployment than their white counterparts, but that divide is highly cyclical: In strong labor markets, it shrinks, but then it skyrockets again during recessions. Black wage gaps change less across business cycles.

Income Ladder

The fact that black workers earn less is a problem in part because it limits their chances at moving up the income ladder. Lower wages can make it harder to afford time off for education and training, for instance.

And it’s particularly worrying that the black-white gap is climbing on the back on unexplainable factors. While a sizable portion of the racial wage divide arises from the different industries and occupations black people work in, their education levels, and their ages, the share owing to factors that aren’t traceable accounts for much of the growth in the wage gap over time.

In 1979, about 8 percentage points of the earnings gap for men was hard to explain, and by 2016, that had risen to 13 percentage points — just under half of the total earnings gap.

“This implies that factors that are harder to measure — such as discrimination, differences in school quality, or differences in career opportunities — are likely to be playing a role in the persistence and widening of these gaps over time,” the authors write.