By Courtney Malloy, Columnist

The Washington Post, April 21, 2019.

While many are confounded by the subject of reparations for slavery, students at Georgetown University have acted on the courage of their convictions.

America, take note.

These students have seen how the legacy of slavery manifests itself in racial disparities — in health, wealth, housing and employment. And they know that the outcomes are no accident. They are the intended results of an economic system rooted in racism and designed to maintain itself in perpetuity.

Maurice Jackson, who teaches courses about slavery, racism, reparations and the Reconstruction era at Georgetown, says many of his students are no longer willing to ignore the problems. They are closing the gaps between the sugarcoated historical myths of their childhoods and the brutal reality of a nation birthed in genocide and bondage.

“They are seeing how ignorance about the past threatens their future. And they are in a hurry to do something about it,” Jackson said.

What they did was modest, yet unprecedented.

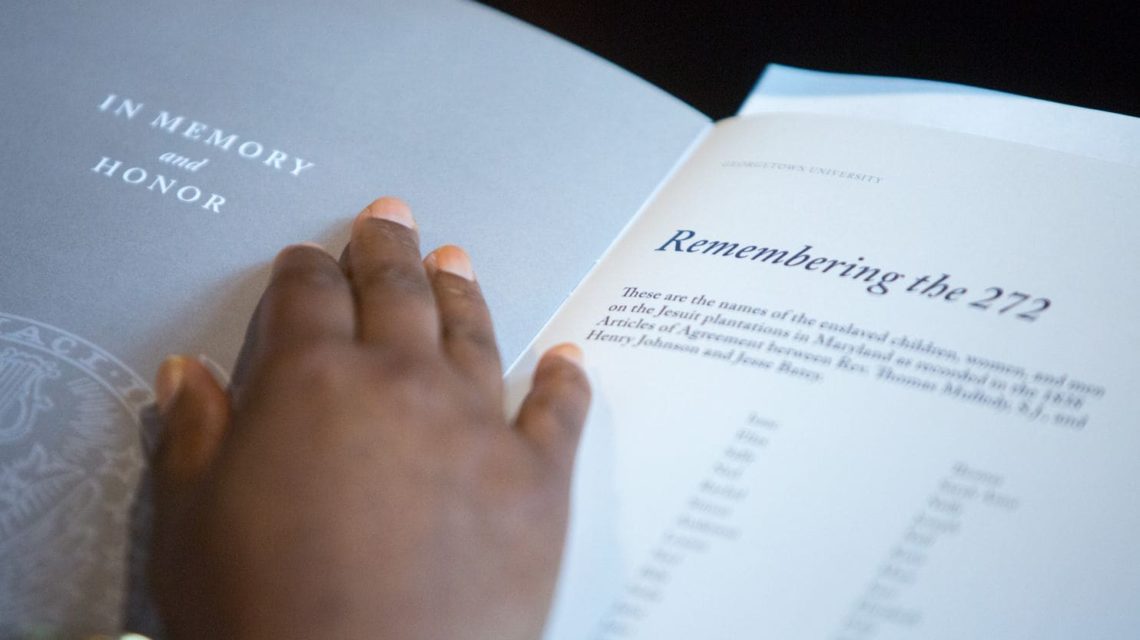

A referendum proposing that undergraduates pay a “reconciliation fee,” in effect reparations, was put to a vote on April 11 — and passed. The beneficiaries would be the descendants of a particular group of 272 enslaved people. They were working around Prince George’s County when, in 1838, the Maryland Province of the Society of Jesus decided to sell them to raise money for a financially strapped Georgetown University.

Students learned of the school’s ties to slavery after a human thigh bone was unearthed during construction of a residence hall in 2014. It was a cemetery site, where the remains of slaves and free blacks had been buried. Subsequent discoveries led the university to make a formal apology in 2017 “for our participation in the evil of slavery,” Georgetown University President John J. DeGioia wrote in an open letter to the campus a day after the student vote.

He said the university would take other steps toward fostering dialogue. “We are pursuing work that is uncharted,” he wrote.

With this month’s vote for paying restitution, the students had charted a path of their own.

[Georgetown’s missing slaves were closer to home than anyone knew]

The amount of the reconciliation fee, to be paid each semester, was a symbolic $27.20. The fees were expected to generate an estimated $400,000 a year. More than 8,000 descendants of the 272 have been identified so far.

Some students complained that the amount was too low, “just an Uber ride,” as one wrote in a post on social media.

Others said the fee increase was unfair, especially to poor students.

Some black students questioned why they should pay reparations when, if anything, they should be receiving them. For others, the answer was clear.

“No problem helping my less fortunate brothers and sisters,” a black student posted on social media. “I’m here because somebody helped me.”

In an op-ed for the Hoya in February, two students, Samuel Dubke and Hayley Grande, made their case for opposing the fee.

“Supporters of the referendum will claim that we, by attending classes, living in dorms and accepting our degrees, owe an intrinsic debt to the descendants of those enslaved people who paid for Georgetown’s existence with their lives,” they wrote. “While we agree that the Georgetown of today would not exist if not for the sale of 272 slaves in 1838, current students are not to blame for the past sins of the institution, and a financial contribution cannot reconcile this past debt on behalf of the university. . . . Georgetown University alone, not the student body, has the obligation to pay for its past transgressions.”

And yet, the measure was approved, overwhelmingly, garnering 66 percent of the 3,845 votes cast. The spring elections, which included candidates for the school senate, drew the largest voter turnout in Georgetown’s electoral history, according to the Hoya.

“The measures advanced in this referendum would put Georgetown on the right side of history and constitute the first reparations policy in the nation,” Georgetown University Student Association President Norman Francis Jr. and Vice President Aleida Olvera wrote in an op-ed for the newspaper.

In an open letter to the university following the vote, DeGioia praised students for “bringing attention to deeply held convictions that we take very seriously.” But he also noted that requiring students to pay such a fee “raises complex issues” that won’t be resolved “immediately or easily.”

[Georgetown gathers descendants for a day of repentance]

The referendum was nonbinding; school officials would still have the last word.

And on April 15, two students filed a lawsuit with the Georgetown University Student Association’s Constitutional Council, seeking to nullify the vote. They contended that the GUSA can hold referendums only on constitutional issues and that the GUSA had violated its own bylaws by holding a vote on raising fees.

The election did not mark the end of the student campaign for reparations. More like a new start.

A remarkable one at that, with most students pushing aside arguments that have doomed reparations proposals in the past.

William Darity Jr., a professor of public policy at Duke University and a scholar on the economics of reparations, told Politico that he was “admiring” what the students at Georgetown were doing. But he also urged them to work on a nationwide effort instead of going only for “piecemeal” solutions.

“We do need to move away from viewing this as a matter of individual guilt or individual responsibility that can be offset by individual payments, towards the recognition that this is a national responsibility,” Darity said.

And yet, a large majority of students had voted to, in essence, begin atoning for the sins of their school.

At Georgetown, where symbols of hate and violence have appeared in recent years — swastikas carved into elevator walls, racist graffiti scrawled in hallways, menorahs defaced — students had created one that could be trumped by none.

It was a vote — the voice of a free people — symbolizing compassion, reconciliation, justice, mercy and collective responsibility.

Lee Baker, a descendant of the 272, was impressed.

“Regardless of what happens,” he told the Hoya, “we will know that Georgetown University students practiced solidarity and decided to ensure that such an historic injustice has a permanent lens for awareness, analysis and action.”

Take note, America. This is what the future looks like.