John Holden, Oklahoma State University

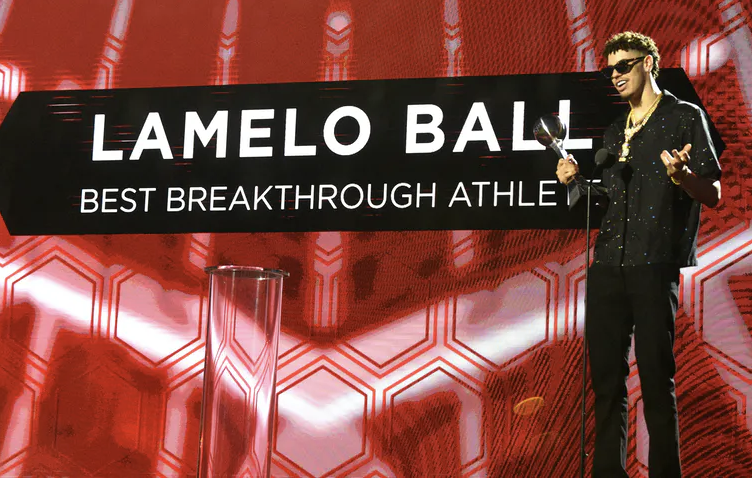

In a recent interview published in GQ, NBA star LaMelo Ball downplayed the importance of college for athletes who aspire to play professional basketball. When asked about his decision to forgo college and play professional basketball overseas before entering the NBA draft, Ball said: “You wanna go to the league, so school’s not your priority.”

The then-19-year-old Ball, now 20, quickly clarified his quotes in GQ via Instagram, stating that he was only referencing his own situation and that while school is “not for everybody,” it is for many people.

LaMelo Ball’s GQ interview is only the most recent point in a long-standing debate over the necessity of college for superstar athletes. Here are four points to help put Ball’s comments into sharper perspective.

The NBA has a minimum-age rule

The NBA implemented its most recent iteration of a minimum-age rule as part of the 2005 collective bargaining agreement. The rule stated that starting in 2006, “U.S. players must be at least one year removed from high school and 19 years of age (by the end of that calendar year) before entering the draft.”

The impetus for the rule change was to improve the quality of play in the league, the belief being that players who had a year removed from high school – time most often spent in college – would have improved skills.

The introduction of the NBA age rule was a surprising solution to something that did not seem to be a significant problem. As law professors Michael McCann and Joseph S. Rosen wrote in 2006, “The new NBA age eligibility rule has generated widespread skepticism and bewilderment, as NBA players who matriculated straight from high school comprise a small, self-selected, and remarkably successful group.” The professors further observed that the main economic beneficiaries of the rule were colleges and universities. The reason is that they would now get one year to have a superstar on their team.

Other options exist for star athletes

The introduction of the NBA’s minimum-age rule created the so-called one-and-done college basketball star. The one-and-done player is a star player who attends college for one year before entering the NBA draft. Star high school players have created recruiting frenzies with colleges competing to attract the players.

Yet some players have chosen alternative routes to the NBA.

Among the high school players who seemed destined for the NBA, Brandon Jennings was the first to decide to spend his year waiting to turn 19 years old somewhere other than college. In 2008, Jennings signed with the Italian professional team Lottomatica Roma, playing one year before the Milwaukee Bucks selected him as the 10th overall pick in the 2009 NBA draft. Jennings’ move overseas was followed by such high school stars as Emmanuel Mudiay, who became a millionaire when he opted in 2014 to sign with Guangdong Southern Tigers of the China Basketball Association. Those moves overseas were followed by those of others, such as LaMelo Ball, who opted to play professionally in Lithuania instead of finishing high school and going to college.

In 2020 the NBA launched G League Ignite, a minor league team that allows players to go professional in the United States without a year in college. The Ignite team played its first season in 2020-2021.

A growing number of players have been opting into the opportunity to play professionally in the NBA’s G League minor league instead of going to college. With salaries as high as $500,000, the money exceeds the value of any college scholarship. This is, of course, not taking into account major changes that allow college athletes to monetize their name, image and likeness.

Endorsement deals are game changers for student-athletes

Since college athletes can now seek endorsement deals, some players may choose college instead of playing professionally overseas or going to the G League Ignite.

As a result of state laws that grant athletes greater autonomy over their rights to profit from their name, image and likeness – and the NCAA’s adoption of an interim policy that serves as the default in states without such laws – athletes in college have the ability to earn substantial amounts of money.

One study in 2020 estimated that some college stars, such as the University of North Carolina’s Cole Anthony, now with the Orlando Magic, could have seen their images become worth more than $450,000 per year while still in school.

Skipping college comes with risks, but so does not going pro

The risks of not going to college, at least immediately, are likely primarily related to the skills that colleges are known for building.

NBA Commissioner Adam Silver has cited maturity as a key reason for the age rule. The commissioner again cited maturity and skill when the league wanted to adjust the age rule to require players to reach the age of 20 to enter the draft. However, that proposal did not succeed.

In the history of professional sports there are dozens of stories of athletes who made millions of dollars only to lose it all through bad financial decisions or trusting the wrong people. The story is so common that ESPN devoted an episode of its “30 for 30” documentary films to the issue.

While college does not provide a guarantee that athletes will make wise financial or personal choices, the college experience gives athletes an additional year to mature. And, in the case of star players, it’s a year of experience being in an intense spotlight.

While many athletes benefit from the college experience, LaMelo Ball is almost certainly right when he says that college is not for everyone. The opportunity to earn life-changing money is presented to so few athletes. Therefore, it is not reasonable to expect those who are athletically gifted enough to go professional to stay amateur and risk injuries that could change or end their career. After all, contracts for tens of millions of dollars create opportunities to go to school well after their NBA career is over.

[Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter.]

John Holden, Assistant Professor of Legal Studies, Oklahoma State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.