Nathan D. Jones, Boston University and Kristabel Stark, University of Maryland

The Research Brief is a short take about interesting academic work.

The big idea

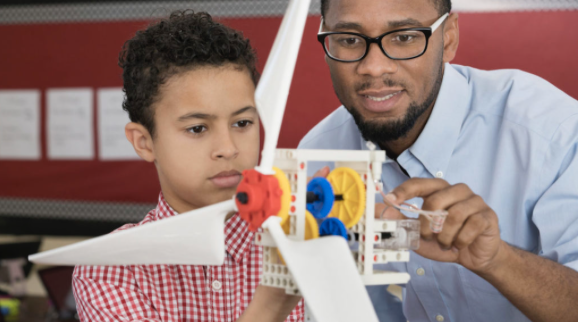

Of all the things teachers do on the job, we found that teachers enjoy interacting with students the most – and that the positive feelings when working with students intensified once schools shifted to remote learning during the pandemic.

This finding is based on a study that enabled us to examine how teachers felt about various aspects of their job before the COVID-19 school closures in the spring of 2020 and during the period immediately afterward.

Since our study began before the pandemic struck, we had no way of knowing our findings would ultimately provide a before-and-after snapshot of how teachers feel about their various job duties.

We’re a team of researchers with expertise in the measurement of teachers’ work. In the fall of 2019, we set out to conduct a long-term study of teachers’ daily work experiences. We used a time sampling approach that enabled us to see how teachers felt emotionally about specific things they do throughout the day.

Partway through our data collection window, schools closed due to COVID-19. Unsurprisingly, we found that teachers’ overall emotional experiences were less positive in the period after the the pandemic hit than before.

But then we took a closer look and began to examine teachers’ emotions during specific types of professional activities, such as direct interactions with students, attending professional development, completing paperwork, planning and preparation and supervising students. That’s when we discovered that teachers actually experienced more positive emotions while working with students after schools closed than before.

Specifically, we found that teachers felt they were more attentive to their students – and more determined to meet their students’ needs – in the weeks following COVID-19-related nationwide school shutdowns.

Why it matters

Our results show how teachers – at least in the early stages of the pandemic – stuck with their students despite sudden changes to their work, such as having to swiftly switch to remote instruction.

Our results are a reminder of how teachers are often driven by what are referred to as the “psychic rewards” of teaching – the psychological benefits of making a difference in the lives of kids through direct interactions.

As schools reopen, our research suggests that one way to keep teachers motivated and engaged is to ensure that they have time to build and maintain relationships with students. This is something we fear could become lost as school leaders are forced to focus on the health and safety aspects of operating schools as the pandemic continues.

What still isn’t known

While our study shows that teachers initially prioritized and invested in their students during the pandemic, we don’t know how long they were able to sustain this response. Other studies have documented that, as the pandemic wore on, teachers across the country reported feeling demoralized and emotionally depleted. And we don’t know if other things made a difference in teachers being able to maintain higher levels of positive emotions while teaching. For instance, what kind of difference did it make if school principals or district superintendents prioritized building relationship with students?

What’s next

For our team, a critical next step is uncovering how teachers have fared as the pandemic has persisted. In those initial months of the pandemic, teachers and leaders alike thought the conditions would be temporary – just a few weeks or months. But educators are now entering their third school year of teaching in a pandemic, and we still have much to learn about the daily effects on teachers of such a profound shift in their work, and more generally, their profession.

[Over 110,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

Nathan D. Jones, Associate Professor of Special Education, Boston University and Kristabel Stark, Postdoctoral Associate, University of Maryland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.