Diego Javier Luis, Assistant Professor of History, Tufts University

One of the most pervasive myths about colonial Latin American society is that it was Catholic, full stop.

It’s a familiar story: As history books tell it, the Europeans brought their religion to the New World, and none were as zealous in their attempts to convert Indigenous people as the Spaniards. Indeed, in the Spanish view, the quest to spread Catholicism to every corner of the world was a central pillar of colonization.

A quick glance at how deeply Catholic much of the region still is – some 57% of Latin Americans – seems to reinforce the idea of Spanish missionaries’ success.

In truth, Spanish control in the Americas was far from absolute. Despite the sweeping proclamations of missionaries who claimed to convert thousands of souls every day to Christianity, spiritual life in the colonies would have made the pope do a double take.

Far from the Vatican

Spain’s colonies were a vast patchwork of borderlands built over the smoldering infrastructure of Indigenous civilizations such as the Mexica and the Inca. Even at the centers of colonial control, like Mexico City and Lima, Spanish power was decentralized, meaning that virtually no policy, order or law was consistently implemented. The reach of the Spanish crown depended as much on the whims of low-ranking administrators as on the king’s own advisers.

The unevenness of colonial authority held true in the realm of religion, as well – a focus of my historical research.

Oftentimes, “conversion” simply meant baptism. Priests would sprinkle water on the convert’s head, give them a “Christian” – i.e., Hispanic – name, and encourage them to attend Mass on Sundays. However, attendance was often spottier than in a post-COVID classroom.

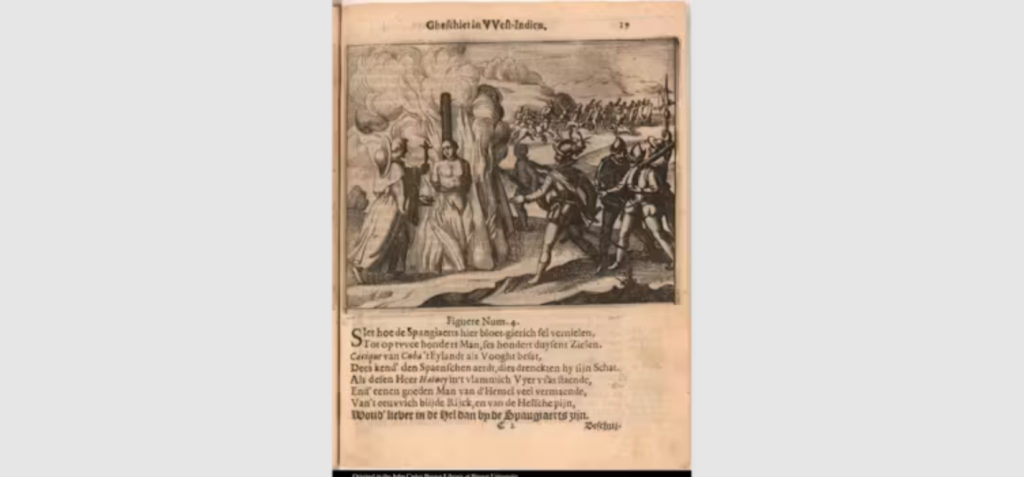

There are many reasons why this was the case. First, the cruelty of some Spaniards hardly made them attractive advertisements for Christianity. The legendary last words of Hatüey, an Indigenous Taíno leader who led a rebellion in what is now Cuba, suffice to make the point.

In the moments before Hatüey was burned at the stake, a priest urged him to convert so that his soul would go to heaven. Hatüey asked if Spaniards went to heaven, too. When the priest responded that “the good ones do, (Hatüey) retorted, without need for further reflection, that if that was the case, then he chose to go to Hell to ensure that he would never again have to clap eyes on those cruel brutes.”

Bartolomé de las Casas, a 16th century missionary, documented this incident to condemn the violence of Spanish colonizers in the Americas.

Second, Indigenous spiritual practices got an unwitting boost from the pope himself. Paul III, pope from 1534-1549, conceded special religious exemptions to Indigenous people in the Americas, since they were new converts, or “neophytes,” in the faith. Effectively, this status meant that they were forgiven for not observing all Catholic practices correctly – not celebrating all holidays, not fasting often, marrying cousins, and so on.

This somewhat flexible – but no less violent – approach to conversion meant that Indigenous spiritual practices often melded with Spanish ones. Perhaps the best example of this religious syncretism is Our Lady of Guadalupe, whom many Catholics revere as an apparition of the Virgin Mary, including Indigenous Catholics. Yet many Indigenous people also identify Guadalupe with Tonantzin. The word means “Our Mother” in Nahuatl, the language of the Mexica, and could refer to multiple goddesses.

Third, as the transatlantic slave trade intensified during the 16th century, spiritual systems from West and West-Central Africa entered the mix. For example, many Africans and their descendants used protective amulets called “nóminas” and “bolsas de mandinga,” and they adapted African healing rituals and medical knowledge to New World environments.

Meanwhile, the lesser-known transpacific slave trade brought thousands of Asians to colonial Mexico and further complicated the religious landscape. My 2024 book, “The First Asians in the Americas,” demonstrates that Asians used a wide variety of beliefs and practices to navigate and even resist the conditions of their enslavement. They made potions, learned enchantments and even publicly renounced their faith in God, Jesus and the saints in order to call attention to unjust treatment.

Paperwork and torture

Spanish authorities were eager to clamp down on these spiritual beliefs and founded new branches of the Inquisition in Lima and Mexico City in the late 1500s. The Spanish Inquisition had been around for nearly a century by this point, policing the boundary between accepted and heretical Catholic practices and beliefs.

While the Inquisition in Europe is infamous for having tried and murdered thousands, the Inquisition in Mexico City reserved execution for only a few dozen cases. Whippings, exiles, imprisonments and public shaming were the norm. Still, the United States carceral system executes more people every few years than the Inquisition in Mexico did over more than two centuries.

Most Indigenous people were exempted from being denounced to the Inquisition, since they were considered Christian neophytes and prone to errors. However, Africans and Asians, as well as their descendants, people of mixed ethnicities, “Moriscos” (converted Muslims), “conversos” (converted Jews), Protestants and even Catholic Spaniards frequently ran afoul of inquisitors.

Inquisition trials generated mountains of paperwork, in part because scribes were obsessive in their thoroughness. Occasionally, they even recorded every exclamation a prisoner cried out in the Inquisition’s notorious torture chambers.

Today, these cases provide rare insights into the spiritual cultures of colonial society’s most marginalized subjects. Non-Europeans were often accused of committing blasphemy and concocting love potions to seduce sailors, soldiers and merchants. They conducted rituals with hallucinogens such as peyote to find stolen objects and lost people. They fashioned charms to shield friends, family and clients from harm.

Though Spaniards punished divination and other unapproved practices, it wasn’t because they considered such rituals pointless or ineffective. Quite the opposite: They believed that they worked but were powered by the devil, and were therefore a force of evil.

Spiritual mosaic

One of the most enigmatic cases I have written about is that of an enslaved South Asian man from Malabar, in southern India, named Antón. In 1652, he appeared before the Inquisition in Mexico City for the “spiritual crimes” of palm reading and divination. He was 65 years old and lived in one of the textile mills infamous for its poor working conditions in Coyoacán, just south of the city.

According to multiple witnesses, Antón attracted a large, multiethnic clientele who sometimes traveled a day in each direction to ask him their pressing questions about the future. By reading palms, Antón would predict “if (someone) would find love, when a baby would be born, if a woman would become a nun, and so on.” Each consultation earned him a few coins, which he split with two weavers who translated from Spanish into Nahuatl for him.

When the inquisitors questioned him, Antón claimed to have learned how to read palms in Malabar and insisted that he had done nothing wrong. In all, divination was not considered as serious a religious infraction as, say, practicing Judaism or Islam, so Antón was condemned to the relatively light punishment of proclaiming his sins publicly after 245 days in prison.

Inquisitorial records from the colonial period are filled with vibrant characters like Antón. There was Domingos Álvares, who became a renowned healer in Brazil, and Antonio Congo, who was said to control storms in what is now Colombia.

They created worlds of knowledge and faith often out of alignment with the strictures of Catholic doctrine. Many of these beliefs have persisted against the odds, surviving into the present. For example, the Afro-Cuban Santería, Palo Monte, Ifá and other religions are thriving in Cuba today despite centuries of discrimination and repression.

Labeling Latin America and its colonial period uniformly “Catholic” silences this rich history. There were, of course, thousands of Catholics in the colonies, and Catholicism was a central tenet of Spanish colonialism. But that is not the full story: Other beliefs thrived and became new realities of colonial life.