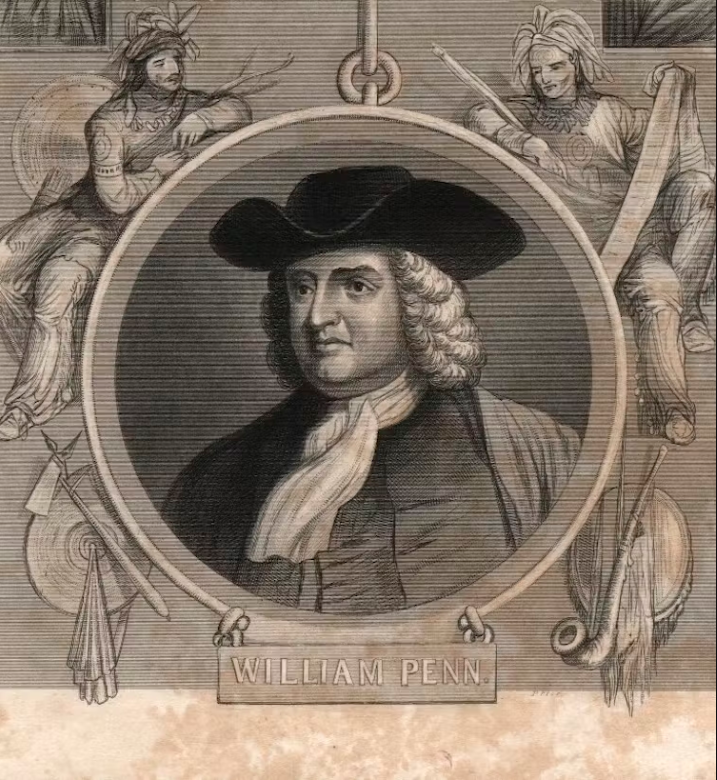

Andrew Murphy, Professor of Political Science, University of Michigan

The National Park Service’s proposed removal of a statue of William Penn from Philadelphia’s Welcome Park turned out to be short-lived. Announced on Jan. 5, 2024, the proposal was quickly pulled from consideration due to a public firestorm.

The Republican leader of the Pennsylvania House of Representatives accused the Biden administration of attempting to “cancel William Penn out of whole cloth.” The proposal was, he said, an example of contemporary left-wing “wokeism.” The state’s Democratic governor had also opposed the plans.

Setting aside debates over whether the statue should remain in its Welcome Park location or not, however, you could ask a slightly different question: Should there be a statue at all?

Born in London in 1644, Penn spent the better part of his adult life advocating against the persecution of religious dissenters. King Charles II granted him an American colony in 1681; he traveled to America the following year, arriving on the ship Welcome – hence the name, Welcome Park.

Penn envisioned his colony as a place where civil and religious liberty could thrive in ways that were impossible in his home country. Although he spent just four years in America, he oversaw the founding of the colonial government as well as its capital city, Philadelphia. Since 1894, a 37-foot statue of Penn has graced the top of Philadelphia City Hall; the present controversy had to do with a 6-foot replica of that statue, located at the former site of Penn’s first Philadelphia home.

Having spent the better part of two decades studying Penn’s life, career and legacy, one thing stands out to me clearly: The Quakerism that transformed Penn’s life in Ireland, in his early 20s, and that he spent the rest of his life serving and promoting, was profoundly hostile to expressions of human vanity. It condemned anything that suggested the elevation of one individual or social class over others.

In other words, William Penn might well have objected to a William Penn statue.

Opposing expressions of vanity

These egalitarian principles – expressed through such vehicles as plain speech and dress, a refusal to remove hats to honor social “superiors,” and a rejection of luxurious apparel and worldly titles – precipitated a bitter rupture between Penn and his father when he became affiliated with the Society of Friends – the formal name for the Quakers – in 1667. They also set him on the path that would lead him to Pennsylvania 15 years later.

Penn made his name as a defender of such plain principles. He was fined by the judge for refusing to remove his hat at his 1670 London trial for unlawful assembly and disturbing the peace, stemming from his preaching to an unauthorized religious gathering. As he put it, “I do not believe, that to be any respect.” Despite numerous threats from the judge, Penn’s jury found him not guilty. The fine for refusing to remove his hat, however, remained in force. He had earlier offered no fewer than 16 reasons against such “hat-honour” in his pamphlet, published in 1669, titled “No Cross, No Crown.”

A decade later, shortly after receiving his colonial charter, Penn took pains to ensure that people knew his American colony was not named for him, which would have represented the height of personal vanity. It was named for his father, a well-known naval commander and friend of Charles II. Though William Penn had proposed “New Wales,” that name was rejected; when he suggested “Sylvania,” the king added “Penn.”

Thus was born Pennsylvania, Penn wrote in a letter to fellow English Quaker Robert Turner, “a name the King [gave] it in honor to my father … whom he often mentions with praise.” Penn even tried to bribe the undersecretaries of state to change the name, “for I feared lest it should be looked on as vanity in me.”

Members of the Society of Friends were so committed to opposing expressions of vanity that for a time, both during Penn’s lifetime and for years after his death, they forbade grave markers entirely.

Unmarked grave or grand mausoleum?

Penn died in 1718 in England. Philadelphia lawyer George Harrison was deputized by Pennsylvania’s government to bring Penn’s remains back from England to Philadelphia in 1882, to mark 200 years since the founder’s first arrival.

But Quakers in Jordans, a village in Buckinghamshire, England, where Penn is buried, insisted that the precise location of Penn’s remains were unknown. The meeting – in other words, the local Quaker congregation – had decided to do away with gravestones entirely in 1766. Friends Meeting clerk Richard Littleboy told Harrison that no one was entirely sure where Penn rested.

Jordans Friends also pointed to the incongruity of Penn being interred in a grand mausoleum, with pomp and fanfare, as Pennsylvania officials planned to do, when Friends’ principles pointed so firmly in the opposite direction.

Littleboy protested “the removal of his remains to a trans-atlantic home, amid the pomp and circumstance of a state ceremonial, accompanied in all probability by military honors and parade,” which he considered “utterly repugnant” to Penn’s “character and sentiment.”

And so Harrison returned to Pennsylvania empty-handed, and Penn remains to this day somewhere in the burial ground outside Jordans Meetinghouse in Buckinghamshire, England.

From City Hall to Welcome Park

The statue in Welcome Park pales, of course, compared to the massive Penn that stands atop City Hall, and which, as an iconic part of Philadelphia’s skyline for more than a century, is surely not going anywhere anytime soon.

The Welcome Park site more generally – which also includes a model of the Slate Roof House, Penn’s first home in Philadelphia – is a historically significant site that merits upkeep and interpretive resources appropriate to 21st century concerns. There are many ways to accomplish these tasks. It is worth noting that representatives from the Native American tribes consulted by the Park Service on the plan for the park apparently were not especially concerned about either the statue or its location in Welcome Park.

The statue itself – in miniature, at Welcome Park, or supersized, on City Hall – implicitly poses its own question: How best to commemorate someone who spent his life guided by the principles of a group that resisted commemoration?