Brandy Thomas Wells, Assistant Professor of History, Oklahoma State University

Nutrition is among the most critical issues of our time. Diet-related illnesses are shortening life spans and the lack of conveniently located and affordable nutritious food makes it hard for many Americans to enjoy good health.

Physicians are also alarmed by nutritional trends they see among the nation’s most vulnerable people: children.

I think that this situation would frustrate Black nutritionist Flemmie Pansy Kittrell if she were alive today. Throughout a trailblazing career that spanned half a century, she worked to enhance food security and to improve both diets and children’s health – under the umbrella of home economics.

While you might view home economics as merely a set of practical skills concerning cooking and budgeting, in the mid-20th century it applied scientific concepts to improve home management, strengthen parenting skills and enhance childhood development.

Kittrell went further, by making the case for healthy and strong families a tool for diplomacy.

While researching Black women’s global activism for rights and freedom, I became aware of Kittrell’s work on behalf of the U.S. State Department, women’s organizations and church groups. I was struck by her pragmatic approach to foreign relations, which emphasized women, children and the home as the keys to good living and national and global peace and security.

I was also stunned by the Black nutritionist’s commitment to shattering traditional assumptions about home economics and improving the health of low-income families around the globe, especially for people of color.

Humble roots

Kittrell, the eighth of nine children born to a sharecropping family, grew up in Henderson, North Carolina. She began working as a nursemaid and cook when she was only 11 years old.

In 1919, Kittrell enrolled at Hampton Institute, a small historically Black Virginia college that later became Hampton University.

A professor encouraged her to major in home economics. She initially rejected the suggestion, claiming the home was “just so ordinary.” Kittrell reconsidered once she learned about Ellen H. Swallow Richards, the first woman to attend Massachusetts Institute of Technology and one of the nation’s earliest female professional chemists.

Kittrell realized that the field was about more than cooking and sewing. Furthermore, women who majored in the subject could then pursue sciences that were closed to them because of their gender.

With a growing belief that the home and family were the basis of society, Kittrell chose to major in home economics rather than political science or economics.

Nutrition and Black families

After her 1928 graduation, Kittrell briefly taught at a high school before becoming the director of home economics and dean of women at Bennett College, a historically Black college in Greensboro, North Carolina. During a 12-year tenure there, she created a nursery center that trained parents and provided child care.

The center also served as a laboratory for experimenting with different teaching techniques.

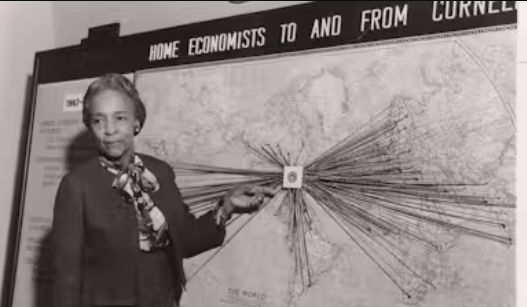

Kittrell drew on this research when she became the first Black woman to earn a doctorate at Cornell University. In her 1936 doctoral dissertation, she argued that the health of Black families could be improved by focusing on infant feeding practices and parental education. She was the first Black woman to get a doctorate in nutrition at any college or university.

In 1940 she returned to Hampton. During World War II, Kittrell and her students taught local families how to ration and substitute food. The home economics department also joined female students in hosting evening activities, including dances for Black military trainees and their families.

Four years later, Kittrell became the head of Howard University’s home economics department. She remained on that faculty for 28 years.

Taking advantage of Howard’s Washington, D.C., location, Kittrell persuaded national leaders that home economics could help transform society at home and around the world. She spent so much time working and traveling for the U.S. government that one biographer called her “a good will ambassador with a cookbook.”

‘Hidden hunger’ at home and abroad

In 1947, the State Department sent Kittrell to Liberia to conduct a nutrition study. Her efforts supported an American commitment to strengthen diplomatic and military with countries around the world.

In her follow-up report, Kittrell explained that while food shortages and hunger were not significant issues, more than 90% of Liberians suffered from vitamin deficiencies, resulting in “hidden hunger.” Though she did not invent the term, she was among the first to draw widespread attention to the issue at home and abroad.

Arguing that what happens in one place often occurs in others, Kittrell implored the U.S. to examine diet issues at home.

In 1949, she published a study comparing the diet and food choices of Black and white Americans. She showed that the illnesses that many Black Americans experienced were tied to racial discrimination in housing, employment and medical services rather than poor decision-making. In later years, academic, professional and activist organizations similarly applied this intersectional lens to nutrition campaigns.

Nutrition and democracy

American foreign policy leaders found Kittrell’s pragmatic and balanced approach indispensable in forging alliances during the Cold War.

In 1950, Kittrell persuaded the State Department’s Fulbright program to send her to India, which had recently won its independence from the U.K. She returned there in 1953 under a government program that provided technical expertise to newly independent nations as a form of diplomacy.

In the 1950s, Kittrell traveled across Africa to improve relations with African states that had criticized the U.S. for boasting of its freedoms while denying basic civil rights to many of its citizens.

In September 1958, the nutritionist traveled to Ghana, the first West African country to gain independence from a colonizing power. She met with Ghanaian political leaders and members of women’s organizations, delivering lectures on home economics and the value of higher education for women.

Ghanaians asked Kittrell about racial incidents, including the 1957 Little Rock crisis, in which a white mob tried to stop nine Black students from integrating a public high school. Kittrell cast this incident, which violated the Brown v. Board 1954 Supreme Court ruling that rendered segregation in public schools unconstitutional, as a Southern dilemma rather than a national one.

She also optimistically emphasized Black Americans’ progress since emancipation and contended that the U.S. Constitution would prevail in ensuring equality.

An appetite for justice

Though Kittrell’s answers sidestepped larger issues of discrimination at home, she claimed to reject U.S. boosterism in her thinking about cross-cultural interactions, family and society.

She argued that newly independent nations had much to teach Americans. Even more, Kittrell claimed to see herself not as a representative of the U.S. but as “a citizen of the world.”

A closer look at Kittrell’s activities reveals that she maintained a strong appetite for justice. Even as a dedicated bureaucratic infighter, Kittrell was willing to move beyond these bounds.

In 1967, for example, she protested apartheid in South Africa, the system of segregation that oppressed that country’s nonwhite communities and privileged a white minority. Incensed by American inaction, Kittrell became one of five Americans to stage a fly-in – an impromptu trip in which she and her colleagues sought to enter the country without visas to dramatize their protest.

In a 1977 interview with the Black Women’s Oral History Interviews Project of the Harvard University Radcliffe Institute, Kittrell hinted that she was engaged in other acts of protest, slyly suggesting that she “was very fortunate not to have gotten into more trouble.”

Three years later in an interview for a faculty profile with Howard University, Kittrell boldly claimed that she had not been “afraid to speak against evil as I see it.”

These statements suggest that she was more of a strategist and activist than many people at the time believed.

Head Start

Kittrell kept traveling extensively in the 1960s.

She took trips to Russia and several African countries on behalf of the United Nations and professional, women’s and religious organizations, such as the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and the United Methodist Church.

Kittrell also increased her focus on the needs of U.S. children.

In the 1960s, 1 in 5 U.S. children lived in poverty. With the conviction that good living began at a young age, Kittrell expanded Howard University’s nursery program with a deeper focus on parents, whom she contended were the key to stronger families.

That center became an early model for the Head Start program, which emerged as part of Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty.

Refusing to “sit still enough to hold hands,” Kittrell never married or had children.

Instead, as her archival papers at Howard University’s Moorland-Spingarn Research Center show, she dedicated herself to assisting others by cultivating strong families through nutritious habits and healthy children.