Charles J. Russo, Joseph Panzer Chair in Education and Research Professor of Law, University of Dayton

Children in American public schools traditionally learned the three R’s: reading, writing and arithmetic. Today, students in more than half of the U.S. states can study a fourth R: religion.

Oklahoma is the most recent state to allow school boards to implement “release time”: off-site classes with religious or moral instruction that K-12 students can attend for part of school days with parental consent. Gov. Kevin Stitt signed House Bill 1425 into law, which authorized the program, on June 5, 2024.

Oklahoma’s law requires school boards to adopt policies permitting students to attend release-time classes for up to three class periods per week. Sessions must be taught at independent entities not on school property. Instructors need not be certificated educators but must keep attendance records, and students are responsible for making up classwork they miss.

In a move likely to generate controversy, the Satanic Temple – a nontheistic religious group that advocates for separation of church and state, along with such ideas as rationality, compassion and bodily autonomy – announced its intention to offer classes on its Facebook account.

Release time may spark debate, but it is not new. Programs were proposed in New York City in 1905, although the first program did not open until 1914, in Gary, Indiana. The number of states with programs grew in the 1930s and ‘40s – and the issue soon made its way to the Supreme Court.

Two cases, two outcomes

The first of two Supreme Court cases on release time was decided in 1948. Controversy arose when a local board in Illinois allowed Jewish, Protestant and Roman Catholic leaders to enter public schools to offer religion classes to children whose parents agreed to let them miss regular class time to participate.

In McCollum v. Board of Education, the Supreme Court struck the program down for two reasons.

First, the justices held that the program impermissibly allowed tax-supported buildings to be used to teach religion, violating the First Amendment – which says that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” Second, the court invalidated the program because it granted faith-based groups invaluable, impermissible aid by helping them to spread their faiths.

Four years later, in Zorach v. Clauson, the Supreme Court reviewed the constitutionality of a different type of release time program from New York City. This program allowed officials to release students from their public schools to attend off-site religion classes.

This time, the justices affirmed that public school officials could accommodate the religious wishes of parents by releasing their children for off-site instruction.

The court upheld release time because public schools were not used for religious instruction. The justices suggested that release time was consistent with recognizing parental discretion and control over their children’s education. The underlying law remains in place.

National landscape

As in Ohio, South Carolina and Tennessee, Oklahoma’s law allows students to earn academic credit for these classes, though they cannot attend in lieu of a core curriculum class. The law explicitly directs school boards to establish standards under which release time can qualify for these elective credits. The law also contains a provision stating boards are not responsible for students during off-campus classes.

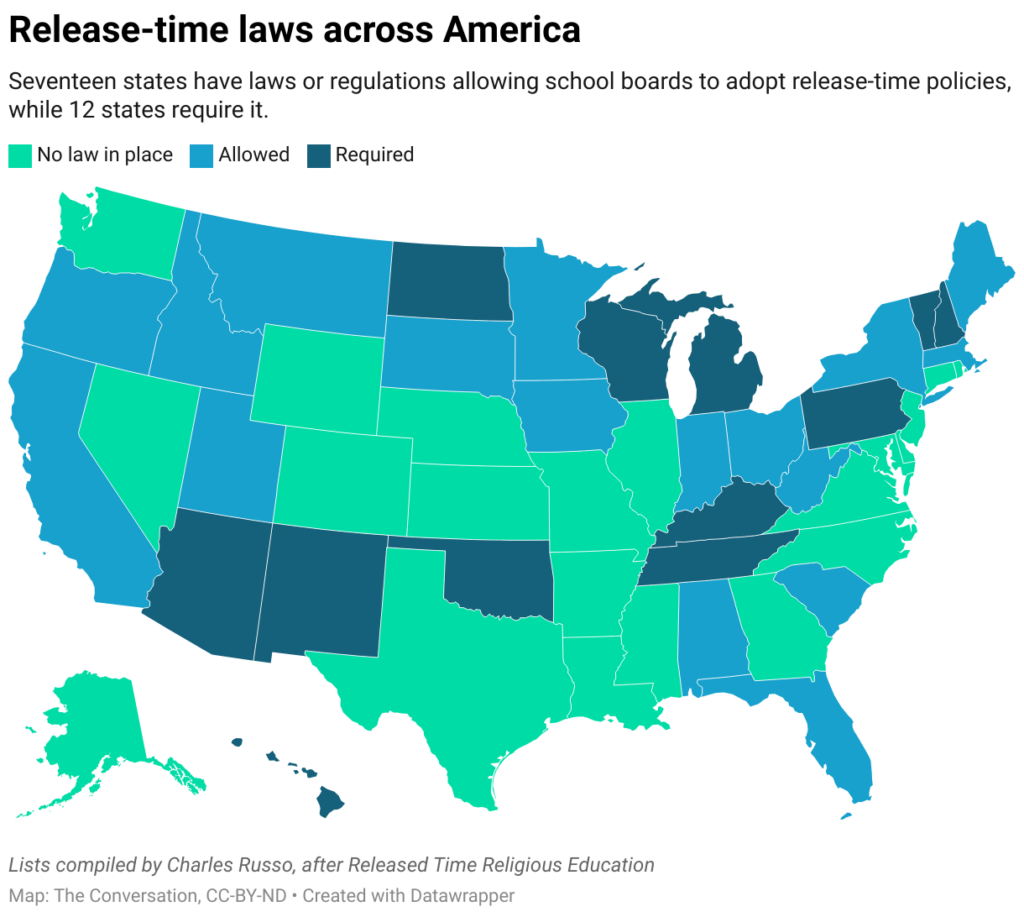

In all, 16 states have laws and one has a regulation giving schools boards the option of adopting policies permitting release time – from California and Montana to Massachusetts and West Virginia.

Moreover, 11 other states and Oklahoma now require boards to adopt release-time policies.

While the remaining 21 states and Washington D.C. do not have laws on release time, parents or religious organizations can petition their local school board to establish a program.

Questions that remain

Oklahoma’s release-time law is consistent with those of other states. Even so, two questions arise.

First, in light of the Satanic Temple’s intent to offer classes, will supporters of this bill defend minority religions’ rights to do so?

Second, how does release time affect learning?

As one who teaches and researches legal issues involving religion and education, I readily concede the value of learning about religions. Yet, at a time when academic achievement is lagging in so many places, partially due to the pandemic, why have children miss instructional time for lessons about their own faiths that they can learn outside school – whether in services, online classes or even online?

I must confess, though, that Zorach v. Clauson was my favorite case in elementary school, though I couldn’t name it at the time. My classmates and I were released early from our Catholic elementary school on Wednesdays so children from public schools could receive religious instruction – the day Carvel ice cream stores had their weekly two-for-one deal.