Frank S. Ravitch, Professor of Law & Walter H. Stowers Chair of Law and Religion, Michigan State University

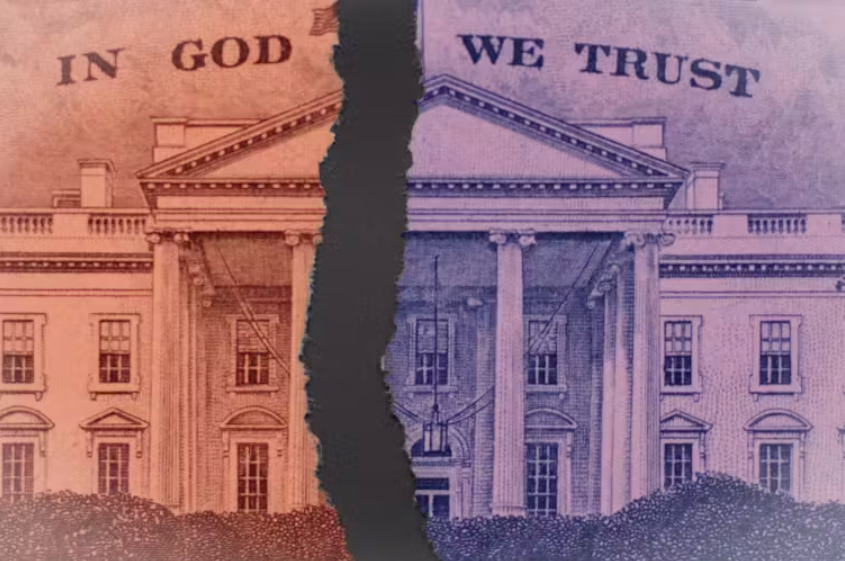

When Louisiana passed a law in August 2023 requiring public schools to post “In God We Trust” in every classroom – from elementary school to college – the author of the bill claimed to be following a long-held tradition of displaying the national motto, most notably on U.S. currency.

But even under recent Supreme Court precedents, the Louisiana law may violate the establishment clause of the First Amendment, which prohibits the government from promoting religion. I make this observation as one who has researched and written extensively on issues of religion in the public schools.

The Louisiana law specifies that the motto “shall be displayed on a poster or framed document that is at least 11 inches by 14 inches. The motto shall be the central focus … and shall be printed in a large, easily readable font.” The law also states that teachers should instruct students about the phrase as a way of teaching “patriotic customs.”

Similar bills are being promoted by groups like the Congressional Prayer Caucus Foundation, a nonprofit that supports members of Congress who meet regularly to defend the role of prayer in government. To date, 26 states have considered bills requiring public schools to display the national motto. Seven states, including Louisiana, have passed laws in this regard.

Recent shift in the law

The Supreme Court has long treated public schools as an area where government-promoted religious messaging is unconstitutional under the First Amendment’s establishment clause. For example, the Supreme Court held in 1962, 1963, 1992 and 2000 that prayer in public schools is unconstitutional either because it favored or endorsed religion or because it created coercive pressure to religiously conform. In 1980, the court also struck down a Kentucky law requiring the Ten Commandments to be posted in classrooms.

At the same time, the court has protected private religious expression for individual students and teachers in public schools.

The Louisiana law comes at a time of rising concerns about Christian nationalism and on the heels of a pivotal court case. In the 2022 case Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, the court overturned more than 60 years of precedent when it ruled that a public school football coach’s on-field, postgame prayer did not violate the establishment clause. In doing so, the court rejected long-standing legal tests, holding instead that courts should look to history and tradition.

The problem with using history and tradition as a broad test is that it can change from one context to the next. People – including lawmakers – are apt to ignore the negative and troubling lessons of U.S. religious history. Prior to the Kennedy decision, history and tradition were used by a majority of the court to decide establishment clause cases only in specific contexts, such as legislative prayer and war memorials.

Now, states like Louisiana are trying to use history and tradition to bring religion into public school classrooms.

A history of ‘In God We Trust’

Contrary to what people often assume, the phrase “In God We Trust” has not always been the national motto. It first appeared on coins in 1864, during the Civil War, and in the following decades it sparked controversy. In 1907, President Theodore Roosevelt urged Congress to drop the phrase from new coins, saying it “does positive harm, and is in effect irreverence, which comes dangerously close to sacrilege.”

In 1956, amid the Cold War, “In God we Trust” became the national motto. The phrase first appeared on paper money the next year. It was a time of significant fear about communism and the Soviet Union, and atheism was viewed as part of the “communist threat.” Atheists were subject to persecution during the Red Scare and afterward.

Since then, the motto has stuck. Over the years, legal challenges attempting to remove the phrase from money have failed. Courts have generally understood the term as a form of ceremonial deism or civic religion, meaning religious practices or expressions that are viewed as being merely customary cultural practices.

The future of the law

Even after the Kennedy ruling, the Louisiana law may still be unconstitutional because students are a captive audience in the classroom. Therefore, the mandate to hang the national motto in classrooms could be interpreted as a form of religious coercion.

But because the law requires a display rather than a religious exercise like school prayer, it may not violate what has come to be known as the indirect coercion test. This test prevents the government from conducting a formal religious exercise that places strong social or peer pressure on students to participate.

The outcome of any constitutional challenge to the Louisiana law is far from clear. Prior cases involving the Pledge of Allegiance offer one example. Though the Supreme Court dismissed on standing grounds the only establishment clause challenge to the pledge it has considered, lower courts have held that reciting the pledge in schools is constitutional for a variety of reasons.

These reasons include the idea that it is a form of ceremonial deism and the fact that since 1943 students have been exempt from having to say the pledge if it violates their faith to do so.

The Louisiana law, however, requires instruction about the national motto.

If the law is challenged in court and upheld, teachers could teach that the motto was adopted when the nation was emerging from McCarthyism and fear of communism was widespread. Moreover, they could teach that many people of faith throughout U.S. history would have viewed this sort of display as against U.S. ideals.

Division is likely

More than two centuries before Roosevelt argued that it was sacrilegious to put “In God We Trust” on coins, the Puritan minister and Colonist Roger Williams famously proclaimed that “forced worship stinks in God’s nostrils.” Williams founded the colony of Rhode Island, at least in part, to promote religious freedom.

Additionally, there is no prohibition on alternative designs for the national motto posters as long as the motto is “the central focus of the poster.” In Texas, a parent donated rainbow-colored “In God We Trust” signs and others written in Arabic, which were subsequently rejected by a local school board. This situation, which gained significant media attention, brought the exclusionary impact of these laws into public view.

It could be argued that accepting wall hangings that favor Christocentric viewpoints – and rejecting those that reflect other religions or add symbols such as the rainbow – is religious discrimination by government. If so, schools might be required to post alternative motto designs that meet the letter of the new law in order to uphold free speech rights and prevent religious discrimination.

The Louisiana law would have been brazenly unconstitutional just two years ago. But after the Kennedy decision, the law may survive a potential legal challenge. Even if it does, one thing is for certain: It will be divisive.