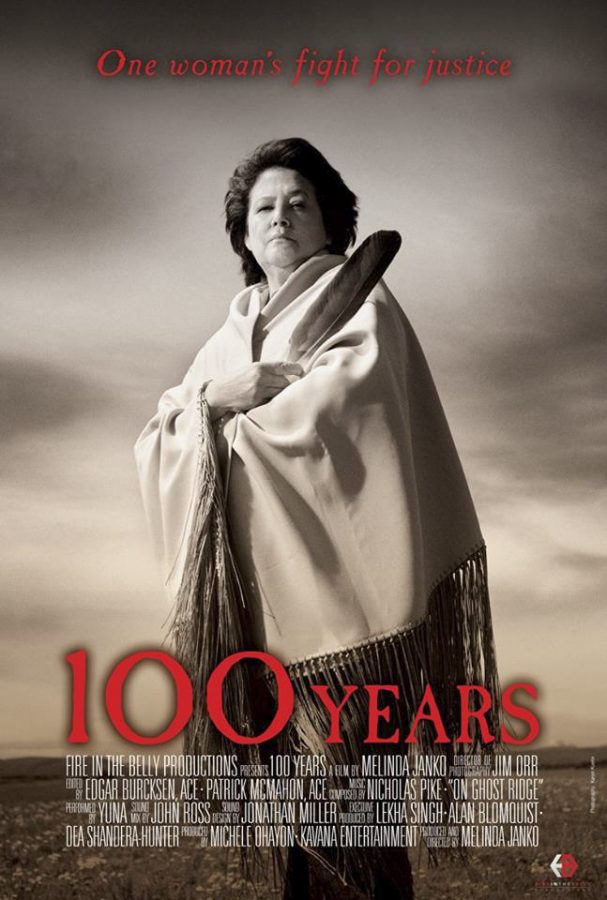

“100 Years” follows one Native American woman through her fight against injustice in modern America.

By Natalie Whalen, Staff Writer

Washington Square News, October 11, 2016 —

As Columbus Day passes, the nation is forced once again to reevaluate its troubled history with its indigenous peoples. With the fight over the Dakota Access Pipeline raising protests from Native Americans who live there, “100 Years” premieres in a highly relevant moment.

The film documents the story of one Native American woman, Elouise Cobell, as she took on the United States government for 30 years with the largest class action lawsuit in history, seeking justice for a century’s worth of money that had been gravely mismanaged by a federal trust.

Director Melinda Janko and Academy Award-nominated producer Michele O’Hayon spent almost a decade and a half filming this inspiring story of justice.

Most Americans today have a rudimentary understanding of how the American government has mistreated Native American peoples — or Indians, the misnomer that has become commonly used for the expansive group — for centuries. “100 Years” tells the story of what many Americans still do not know: that these citizens are still heinously mistreated today.

The first half of the documentary sets the scene. Viewers learn the stories of people like Mad Dog Kennerly and Cora Bunnie, American Indians with vast oil reserves on their land who received pennies for the millions of what was extracted from their lands. These individuals, who should be some of the richest in America, were living in abject poverty with little means to rectify their situation.

That is, until Blackfeet warrior Elouise Cobell started asking questions about the mismanaged funds as the treasurer of her tribe. The rest of the film proceeds to follow Cobell and her team through the latter half of her 30-year fight to secure justice for her people against the fraud and corruption of one of the largest governments in the world. The sheer sacrifice of this Montana woman is remarkable, as she left her home state to lobby in Washington D.C., even giving up her leadership position in Montana’s Elvis Presley fan club.

What’s interesting about the film is the way in which politics played into Cobell’s success. We see the fruits of her efforts evolve as we pass through three presidential administrations. It became evident that the mismanaged trust was no oversight; in one instance a Republican federal judge, Royce C. Lamberth, was removed by the Bush administration for his affirmative opinion that the United States government had mismanaged Indian funds.

One of the highlights of the film includes a particularly tense courtroom argument with U.S. Senator turned 2008 Republican Presidential candidate John McCain, in which Cobell firmly stands her ground. For those Native Americans affected by this case, the 2008 election was so much more important to them than it was to other Americans — it was not until Obama entered the White House that Cobell’s 30-year struggle proved worthy.

Audiences are left wanting more. But being a documentary, it is difficult to capture every courtroom battle in a way that is accessible to an audience within two hours. The arc of the narrative is indefinite at times. Some of the individuals introduced only appear in a couple of scenes that have little discernible benefit to the developing storyline. There is no doubt that it is difficult to construct a successful narrative with 30-plus years worth of material to work with; still, given these circumstances, “100 Years” does a very good job of maintaining audience interest and delivering a film that is both touching and illuminating.

“100 Years” opens in New York on Oct.