By Ronald Hall, PhD, Professor of Social Work, Michigan State University

The Conversation, February 2, 2018 —

For black Americans, skin color is a complex topic.

Whenever a black celebrity lightens his or her skin – whether it’s pop star Michael Jackson, retired baseball player Sammy Sosa or rapper Nicki Minaj – they’re usually greeted with widespread ridicule. Some accuse them of self-loathing, while many in the African-American community view it as a rejection of black identity.

Increasing numbers of mixed-race births have further complicated matters, with light-skinned blacks occasionally being accused of not being “black enough.”

At the same time, The New York Times recently detailed the growing popularity of glutathione treatments. The antioxidant, which is administered intravenously, can deactivate the enzyme that produces darker skin pigments.

The article noted that while these treatments have become hugely popular in Asia, “it is also cropping up among certain communities in Britain and the United States,” with demand “slowly growing.”

As someone who has studied and written about the issue of skin color and black identity for over 20 years, I believe the rise of glutathione treatments – in addition to the growing use of various bleaching creams – reveal a taboo that African-Americans are certainly aware of, but loathe to admit.

Though they might criticize lighter-skinned black people, many people of color – deep down – abhor dark skin.

Lil’ Kim performs during the 2015 BET Awards in Los Angeles, Calif. Kevork Djansezian/Reuters

The power of fair skin

There are few places in the world where dark skin isn’t stigmatized.

Many Latin American countries have laws and policies in place to prevent discrimination relative to skin color. In many Native American communities, “Red-Black Cherokees” were denied acceptance into the tribe, while those with lighter skin were welcomed.

But it is in Asia where dark skin has seen the longest and most intense level of stigma. In India, dark-skinned Dalits, for thousands of years, were viewed as “untouchables.” Today, they’re still stigmatized. In Japan, long before the first Europeans arrived, dark skin was stigmatized. According to Japanese tradition, a woman with fair skin compensates for “seven blemishes.”

The United States has its own complicated history with skin color, primarily because “mulatto” skin – not quite black, but not quite white – often arose out of mixed-race children conceived between slaves and slave masters.

In America, these variations in complexions produced an unspoken hierarchy: Black people with lighter complexions ended up being granted some of the rights of the master class. By early 19th century, the “mulatto hypothesis” emerged, arguing that the “white blood” of light-skinned slaves made them smarter, more civilized and better looking.

It’s probably no coincidence that light-skinned blacks emerged as leaders in the black community: To white power brokers, they were less threatening. Harvard’s first black graduate was the fair-skinned W.E.B. Du Bois. Some of the most prominent black politicians – from former New Orleans Mayor Ernest Morial, to former Virginia Gov. Douglas Wilder, to former President Barack Obama – have lighter skin.

Fair skin and beauty

In 1967, Dutch sociologist Harry Hoetink coined the term “somatic norm image” to describe why some shades of skin are favored over others.

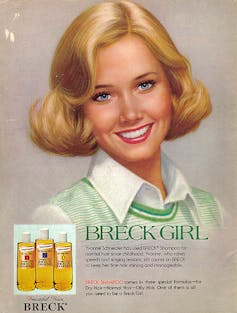

In America, some trace the emergence of light skin as the “somatic norm image” for all modern-day races to the 1930s advertising campaign of Breck Shampoo.

A print advertisement features the fair-skinned Breck Girl. Jamie/Flickr.com, CC BY

To market its product, the company created the “Breck Girl.” In advertisements, her fair, alabaster skin was touted as the perfect ideal of feminine beauty. Few considered the devastating affects a glamorized image of light skin might have on the self-esteem of dark-skinned Americans – in particular, women.

In a 2008 study, researchers at the University of Georgia called skin color distinction “a well-kept secret” in black communities. “The hue of one’s skin,” they wrote, “tends to have a psychological effect on the self-esteem of African-Americans.”

Yet they also noted that existing research on the relationship between skin color and self-esteem didn’t even exist. Fear of being perceived as a race traitor continues to make the topic taboo in the United States – in a way which exceeds that in places like India or Japan.

To obtain a fairer complexion, many apply bleaching creams. Some of the most popular are Olay, Natural White, Ambi Fade Cream and Clean & Clear Fairness Cream.

While these creams can work, they can be dangerous: Some contain cancer-causing ingredients. Despite the potential danger, skin bleaching cream sales have grown. By 2024, it’s projected that global profits will reach $31.2 billion.

In the U.S., sales are difficult to assess; African-Americans are reluctant to admit that they bleach. For this reason, American companies will often market their creams by using abstract language, claiming that the creams will “fade,” “even the tone” or “smooth out the texture” of dark skin. In this way, black people who buy the creams can avoid confronting the real reasons they feel compelled to purchase the product, while skirting accusations of self-hate.

The harmful effects of the ‘bleaching syndrome’

After studying skin color for years, I coined the term “bleaching syndrome” to describe this phenomenon.

I published my first paper on the topic in 1994. Put simply, it argues that African-Americans, Latinos and every other oppressed population will internalize the somatic norm image at the expense of their native characteristics. So even though dark skin is a feature of African-Americans, light skin continues to be the ideal because it’s the one preferred by the dominant group: whites.

The bleaching syndrome has three components. The first is psychological: This involves self-rejection of dark skin and other native characteristics.

Second, it’s sociological, in that it influences group behavior (hence the phenomenon of black celebrities bleaching their skin).

The final aspect is physiological. The physiological is not limited to just bleaching the skin. It can also mean altering hair texture and eye color to mimic the dominant group. The rapper Lil’ Kim, in addition to lightening her skin, has also changed her eye color and altered her facial features. The fact that so few in mainstream culture can even acknowledge the existence of the bleaching syndrome is a testament to how taboo the topic is.

The solution to the bleaching syndrome is political. The disdain for dark skin today is similar to disdain for kinky hair in the 1960s. African-Americans’ dislike of their natural hair was so ingrained that the first black millionaire, Madam C.J. Walker, was able to accumulate her fortune by selling hair-straightening products to black folks.

“Black is Beautiful” – a slogan popularized at the tail end of the 1960s – was a political statement that sought to upend the negative associations many Americans, including many African-Americans, felt toward all things black. In response, the Afro became a popular hairstyle, and black entertainers, from Sammy Davis Jr. to Lou Rawls, proudly grew out their hair, refusing to apply hair straightening products.

“Back to Black” – a nod to the “Black is Beautiful” campaign – is a political statement that could address the impulse many feel to bleach their dark skin. It has the potential to reverse the disdain for such skin and hence those so characterized. Even black celebrities who possess fair skin could help glamorize dark skin by repeating the slogan and paying tribute to the numerous dark-skinned beauties whose attractiveness goes seldom acknowledged: Lupita Nyong’o, Gabrielle Union and Janelle Monae.

These dark-skinned black women would qualify as beautiful by any standards – regardless of skin color.

Ronald E. Hall, PhD

Ronald Hall, PhD, Professor of Social Work, Michigan State University – My research interests include mental health, intra-racial racism, Bleaching Syndrome, black/white conflict, organizational issues, and race relations. My social work research interests extend to four areas: special populations, human behavior and the social environment, social welfare policy and services, and research methods.