By

Cyberspace isn’t any fairer than the workplace, researchers reported Thursday. They found that artificial intelligence programs like search engines or software translators are every bit as prejudiced as real, live human beings.

It may not be the fault of the programmers, the team at Princeton University reports in the journal Science. It may just be that the body of published material is based on millennia of biased thinking and practices.

So someone named Leroy or Jamal is less likely to get a job offer, and more likely to be associated with negative words, than a similarly qualified Adam or Chip.

And AI thinks Megan is far more likely to be a nurse than Alan is, Aylin Caliskan and colleagues found.

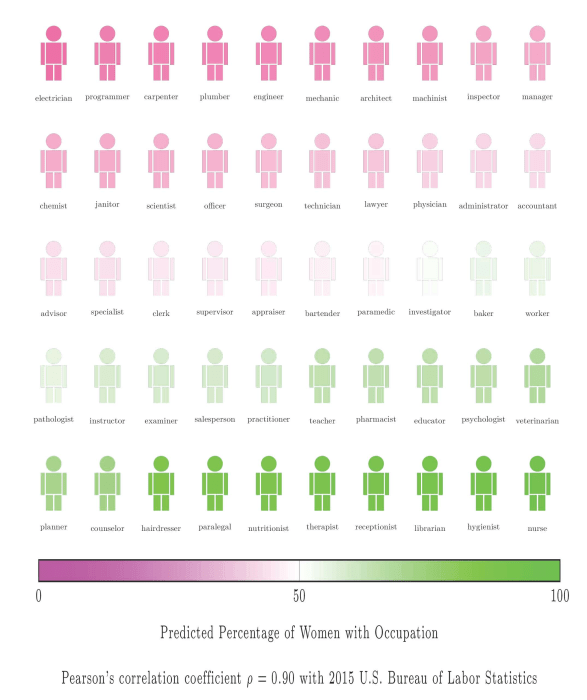

Predicted percentage of female names with occupations [Credit: Aylin Caliskan] / Science

They used some of the same tests that are standard psychological tests for people, including the Implicit Association Test, which measures how long it takes to link different words.

For instance, people are far quicker to link the names of flowers with pleasant words such as “caress” than with unpleasant words such as “hatred.” The opposite goes for insects such as maggots, which people — and, it turns out, software — link much more easily with word such as “stink.”

The results are clear.

“Female names are associated more with family terms whereas male names are associated more with career terms,” Caliskan said.

“We show that cultural stereotypes propagate to artificial intelligence (AI) technologies in widespread use,” they wrote in their report, published in the journal Science.

It’s easy for software to learn these associations just by going through publications and literature, said Joanna Bryson, who helped oversee the research.

“Word embeddings seem to know that insects are icky and flowers are beautiful,” Bryson, who is also on the staff at Britain’s University of Bath, wrote in her blog.

“You can tell that a cat is more like a dog and less like a refrigerator … because you say things like ‘I need to go home and feed my cat’ or ‘I need to go home and feed my dog’ but you never say ‘I need to go home and feed my refrigerator’,” she said.

“The language itself, just learning language, could account for the prejudices.”

Caliskan found even language translation programs incorporated the prejudices. Caliskan demonstrated on a video, showing how translation software turned the gender-neutral Turkish term “o” into “he” for a doctor and “she” for a nurse.

“There are number of ways in which AI could imbibe human bias,” said Arvin Narayanan, assistant professor of computer science at Princeton.

“One is from its creators or its programmers. Another is from the data that’s fed into it that comes not so much from its programmers but from society as a whole,” Narayanan added.

“The biases and stereotypes in our society reflected in our language are complex and longstanding. Rather than trying to sanitize or eliminate them, we should treat biases as part of the language and establish an explicit way in machine learning of determining what we consider acceptable and unacceptable.”