The survey is the largest U.S. study on the topic of equity and talent retention in architecture.

By Wanda Lau

Archictect, October 31, 2016 —

Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

AIA San Francisco’s Equity by Design (AIASF’s EQxD) committee released the early findings from its 2016 Equity in Architecture Survey during its fourth (sold-out) symposium, Equity by Design: Metrics, Meaning, and Matrices, held on Oct. 29 at the San Francisco Art Institute. The results, organized into two frameworks—career dynamics, or the challenges and perceptions of working in the profession; and career pinch points, the milestones that make or break one’s advancement—show an underrepresentation of women and minorities in leadership roles and a clear gender pay gap regardless of one’s experience and title. Moreover, the survey identifies the specific predictors of one’s success in architecture.

The survey continues the work of EQxD’s landmark 2014 survey that investigated the pinch points in the architecture profession and their effect. Though the AIA and the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB) also publish regular reports on diversity and demographics, EQxD’s efforts offer a detailed and candid look at issues that are gaining mainstream attention—finally—among the general workforce: income disparity, the performance review process, work-life balance, and the challenges of balancing caregiving with career.

The 2014 grassroots effort drew 2,289 responses, from women and men on a 2-to-1 ratio, and helped lead to the successful passage of AIA Resolution 15-1: Equity in Architecture. But the online survey was open to anyone, with no restriction, so self-selection by respondents was a likely bias.

For the 2016 survey, participation was by email invitation only. The AIASF EQxD committee, which includes founding chair Rosa Sheng, AIA, co-chair Lilian Asperin, AIA, and chair of the EQxD Research committee Annelise Pitts, Assoc. AIA, enlisted the help of the AIA, state and local AIA chapters, AIA Students, the Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture (ACSA), the National Architectural Accrediting Board, NCARB, and the National Organization of Minority Architects to create an email list. Several design firms also volunteered to participate, as did several architecture schools, which sent the survey to their alumni.

Between Feb. 29 and April 1, 8,664 respondents—50.7 percent women and 49.2 percent men—completed the 2016 survey’s 80-plus questions, resulting in “the largest survey on the topic of equity in architecture,” says ACSA director of research and information Kendall Nicholson, Assoc. AIA. (For reference, the U.S. has 110,168 licensed architects and 41,542 emerging architects in the AXP process, according to NCARB’s 2015 “By the Numbers” report.)

Select findings from the survey are summarized below.

Respondent Demographics

The 2016 survey was taken by architects and designers in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and nearly two dozen countries across six continents. The racial or ethnic makeup of respondents is generally representative of design professionals in the United States. The nearly equal percentage of male and female respondents means that women—and in particular, those with fewer years of experience—are slightly overrepresented in the survey (about 42 percent of licensed architects are women, according to NCARB). Consequently, the research team was careful to report only responses that were statistically significant. The team also couldn’t do “a baseline comparison between men versus women without considering experience,” Pitts says. “Otherwise we would just be comparing the experiences of old men versus young women.”

Survey respondents’ years of experience. Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

Diversity among survey respondents versus years of experience. Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

The fewer the number of years of experience, the more diverse the respondent pool, suggesting a tide of diversity is making its way into the design pipeline. Because this survey is not a longitudinal study, which tracks respondents through time, the longevity of this pattern is unknown. However, Pitts says, “Architecture will likely become a more diverse profession than it is today.”

Firm Culture

The survey found that the top reasons for accepting a job included the quality of the employer or firm’s projects, opportunities for learning, and firm reputation. At the other end, the most common reasons for leaving a job were better opportunities, lack of advancement, and low pay.

Respondents were most likely to report a positive work culture if their firm shares their values and if they find their work meaningful. Respondents who felt that their firms failed to prepare them for their work, or who report no office friendships were most likely to report a negative work culture.

Top correlations with positive or negative assessment of workplace culture. Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

Firms can improve workplace culture by organizing social events, which more than half of respondents said would help, and by involving employees in strategic decision-making and company goals.

Professional Development

Though most architecture graduates “aspire to become a principal at a firm one day, the desire plummets over time,” Pitts says. From the outset, women are nearly 20 percent less likely than men to want to lead a firm. “There is good social science that is true for all professions,” she says. Men who reported adeptness with negotiation skills and women who highlighted their creativity and design skills were most likely to aspire to be a firm partner, principal, or owner.

Probability of aspiring to be a principal. Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

The majority of female survey participants report having a member of senior management advocate for them, while nearly half of male respondents say they do not have a champion at work. Those who found a mentor in a firm leader were more likely to feel more energized by their work, foresee staying at their jobs, and perceive their career with more optimism. In particular, women with mentors were more likely to have better perceptions of work–life balance.

Sources of professional guidance. Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

Pay Equity

The survey found that architecture is certainly not immune to the issue of the gender pay gap. Among all respondents, the average annual salary of women in architecture was 76 percent of that for men: $71,319 as compared to $94,212. (The national average among all industries is typically reported to be between 78 percent and 82 percent.)

The researchers dug deeper into the numbers and found that anyway they sliced it, the average wage of male respondents was always higher than that of female respondents, whether it was by years of experience, firm size, and project title—thus addressing the common question of whether gender pay gap statistics look at equal pay for equal work. Notably, the highest discrepancy in pay between men and women was among those with the title design principal. Essentially, when it comes to wages in architecture, it is all bad news for women. (See further below for results indicating the gender pay gap when factoring in highest degree attained, caregiver status, and project market sector.)

Average salary by years of experience. Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

Average salary by firm size. Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

Average salary by project role. Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

Women and men were about equal in their attempts to negotiate their salary, but men were more likely to be successful in their attempts and more likely to be satisfied with their salary and bonuses. Male respondents who reported always being satisfied with their compensation also reported the highest salary range.

Negotiation history and wage satisfaction. Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

Work–Life Balance

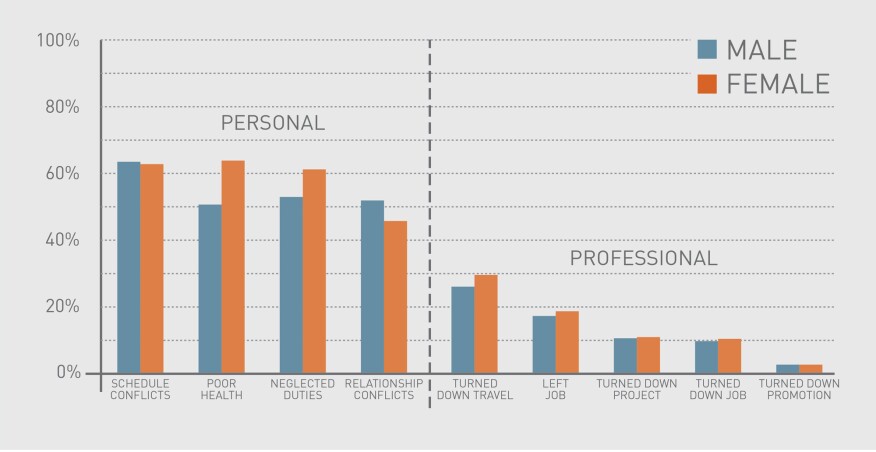

Though workdays may seem endless, particularly around project deadlines, most survey respondents reported an average workweek of 40 to 50 hours, and had time to pursue interests outside of work. However, “the average hours worked per week is not telling the whole story about work-life flexibility, and employers need to know that,” Pitts says. As a result of issues in work–life flexibility, men reported a higher likelihood of experiencing conflicts in personal relationships and appointments, and women increasingly reported a detrimental effect on personal physical or emotional health as well as falling short on personal responsibilities.

Challenges due to work-life flexibility. Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

Generally speaking, respondents found the ability to work whenever and from wherever was the most effective in helping fostering work–life flexibility. Women were more likely to take advantage of work–life flexible policies if leaders at their firm led by example and used the benefit options as well.

Five and 7 percent of male and female respondents, respectively, reported feelings of burnout. These female respondents were also much more likely to report not knowing the firm’s performance evaluation criteria.

Percentage of respondents who report feeling burned out or engaged, by gender. Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

After Architecture

About 11 percent of survey respondents reported leaving the traditional notion of a career in architecture (practicing in a firm or as a solo practitioner), but the “vast majority is still involved in architecture” in a related field, Pitts says. Of those who have left, women were more likely to volunteer or write about design while men were more likely to head into construction, real estate, or a public agency related to the built environment.

The role of designers, who have left architecture, in the built environment. Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

The 2016 survey also asked questions to parse the four pinch points from the 2014 survey—paying dues, licensure, caregiving, and the glass ceiling—as well as a new pinch point, studio.

Education and Studio

Some good news regarding architecture education: 71 percent of respondents believe their schooling prepared them well for their career, though men were more likely than women to say so. Design thinking, construction methods, and graphic representation were cited as the most useful courses, while respondents wanted to learn more about professional practice, construction methods, and building systems. “School is clearly doing something right,” Pitts says.

Survey respondents’ satisfaction with their education. Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

Still the highest degree attained by respondents didn’t change the finding that women on average made less than men in architecture.

Average salary by degree type. Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

Paying Dues

From zero to five years of experience, when designers go through the culture shock from the bubble of studio and the reality of working with client, budget, and time demands, male respondents were more likely to have roles in project design leadership and BIM or design technology management, while female respondents were more likely to oversee office events. The adage of women “taking on office housework, especially early on, does bear out pretty strongly,” Pitts says.

Typical office tasks for respndents with fewer than five years of experience. Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

As this is a period of high attrition, the survey identified one-on-one mentoring and transparency in performance evaluation criteria as essential as to whether someone stays in the profession.

Licensure

The average time for respondents to become licensed was between six and seven years after graduation. Men were less likely to report obstacles in the licensure process than women.

Greatest obstacles to licensure. Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

The top reasons for achieving licensure were the ability to call oneself an architect; the ability to practice independently, and the elevation in professional standing. By far, the top reason for not pursuing licensure was that the respondent felt it was unnecessary for meeting their career goals.

Caregiving While Working

Parents averaged higher measure-of-success (MoS) scores than nonparents. (These scores, calculated from 14 survey questions covering issues such as job satisfaction, career optimism, work–life balance, and burnout and engagement to determine a respondent’s perceived success, served as a benchmark for analyzing other metrics.) Despite female parents having higher MoS scores than male or female non-parents, they averaged the lowest salary among all experience levels. Pitts notes that salary raises often are a percentage of one’s current wage, and “those differences do compound over time.”

Committee Average salary by caregiver status

Despite a similar number of male and female respondents reporting to be caregivers, women were more likely to report taking on more childcare responsibilities. The likelihood of burnout for respondents who are parents decreased as their involvement with childcare decreased. Furthermore, when respondents acknowledged that their partner was responsibility for more of the childcare, their average number of hours worked was higher as was their likelihood of aspiring to be a firm leader.

Likelihood of parents versus non-parents to face work-life challenges. Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

The Glass Ceiling

“There is a glass ceiling in architecture,” Pitts says. Though the lack of diversity in leadership roles may be attributed in part to pipeline issues, the lower likelihoods of women and non-white men at all levels of experience are hard to overlook.

Likelihood of being a principal. Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

Additionally, when respondents were asked who comprises their firm leadership, about 65 percent said mostly or all men, while less than 15 percent responded mostly or all female.

And, more sobering, further debunking the notion of equal pay for equal work, men were paid more than women regardless of the types of project they worked on. The biggest difference was between architects designing single-family residential projects, where men earned $20,000 more than women on average.

Average salary by project type. Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

The differences in salary, career advancement, and career perception between men and women revealed in the 2016 Equity in Architecture Survey are stark. However, pinpointing the differences to gender alone would be simplistic and inaccurate. “Gender wasn’t the driving predictor of success within the profession,” states AIASF EQxD’s press release. Rather, “factors like transparency in the promotion process, having access to a senior leader in one’s firm, receiving ongoing feedback about one’s work, sharing values with one’s firm, and having meaningful relationships at work were much more strongly correlated with all of these measures of success.”

Unfortunately, for now, male respondents were more likely to say they had access to each of these factors.

Metrics of success in the architecture profession. Atelier Cho Thompson courtesy AIA San Francisco Equity by Design Committee

For all of the early findings of AIASF EQxD’s Equity in Architecture Survey 2016, go to Equity by Design’s website.

Wanda Lau, LEED AP, covers technology for ARCHITECT and Architectural Lighting. She likens writing to running—both feel terrible starting out, but become easier along the way. Follow her on Twitter.