By Brian Ward

The Conversation, October 28, 2017 —

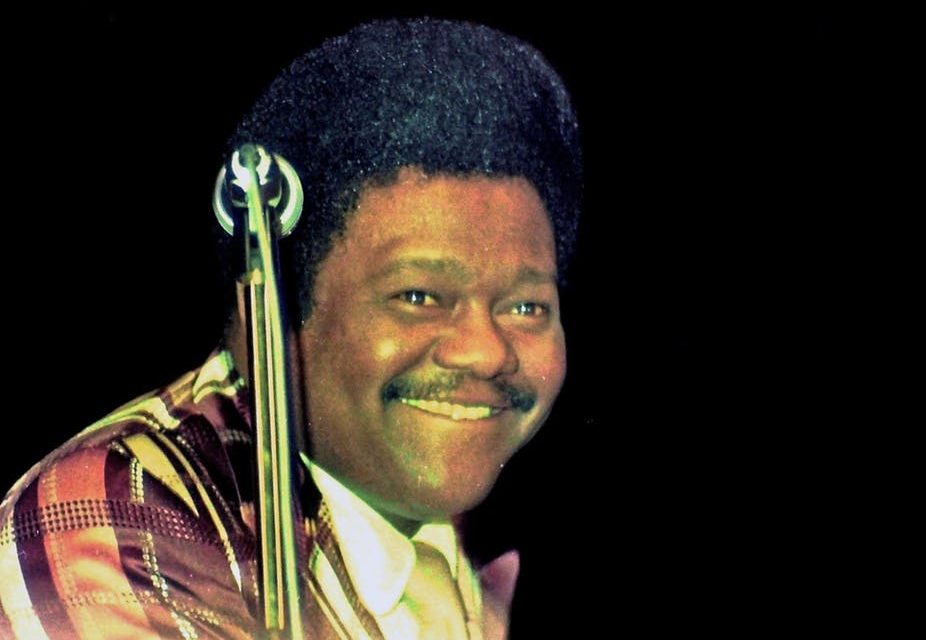

Fats Domino in 1967. Credit Clive Limpkin/Daily Express, via Getty Images

Rock’n’roll trailblazer Antoine “Fats” Domino has died, aged 89. With his beguiling smile, genial image and effervescent shuffle-boogie sound, it’s hard to think of him as radical figure in American culture. Yet, in the mid-1950s, Domino was at the heart of a revolution that transformed western music and had profound social repercussions.

On May 4, 1956 Domino was headlining a rhythm and blues show at the American Legion Auditorium in Roanoke, Virginia. In keeping with the segregation laws of the day, whites and blacks were consigned to separate areas. On this occasion, African-American fans occupied the dance floor while 2,000 whites crammed into a balcony designed for about half that number. Some white fans tried to escape the crush by going downstairs to the less densely packed main floor where, as incredulous local journalists noted, they were spotted sharing seats and “actually dancing” with black rock and roll enthusiasts as Domino ran through an already extensive catalogue of hit songs.

The spectre of black and white youngsters defying southern segregation proved too much for some in the balcony, who began to hurl bottles down on the unexpectedly integrated scene below. After the show ended, an angry white crowd even pursued Domino and his fellow black performers back to the Dumas Hotel on Henry Street in the heart of Roanoke’s African-American community. Like other white southerners who opposed the spread of rock and roll music, the mob sensed that somehow this music – played by black and white musicians who drew on black rhythm and blues and white country and pop influences to craft a style that was adored by young black and white fans – represented a serious threat to the racial apartheid of the Jim Crow South. But it was too late. Thanks to Fats Domino and his fellow rock and rollers the integrated musical genie was out of the segregated bottle.

In 1950, the portly Domino had enjoyed his first hit with The Fat Man, a rollicking, good-natured ode to his amorous powers penned by his long-time collaborator, band leader and producer, Dave Bartholomew. With its pulsating piano and irresistible riffing horns, the recording pointed the way forward to what would soon become known as rock and roll.

But The Fat Man was only a hit on the rhythm and blues charts, which essentially monitored the sales of recordings by black artists to overwhelmingly black audiences. Aside from occasional crossover hits by the likes of Louis Jordan and Nat King Cole, black artists rarely made much of an impression on the nominally white pop charts.

Within a few years, however, Domino was picking up significant sales among white audiences. In 1952, his number one rhythm and blues hit Goin’ Home also made the pop charts, as did the deliciously maudlin Going to the River the following year.

By mid-decade, as Chuck Berry, Bo Diddley, Elvis Presley, Jerry Lee Lewis and countless other black and white acts secured major hits on both sides of the racial divide, Domino’s career was in full swing. “A lot of people seem to think I started this business. But rock ‘n’ roll was here a long time before I came along,” Presley told reporters in 1957. “Let’s face it,” he conceded, “I can’t sing like Fats Domino can. I know that.”

Despite falling victim to the cover phenomenon, whereby white artists released versions of his new recordings hoping to capture the white pop market, many of Domino’s classic tracks, among them Ain’t that a Shame, Blueberry Hill, I’m Walkin’ and Whole Lotta Loving, were major pop as well as huge rhythm and blues hits.

By the end of the decade Domino was the most commercially successful of all black pop stars, earning some $700,000 annually from live performances, record sales, publishing royalties (he wrote or co-wrote many of his recordings) and appearances in a string of rock and roll movies such as The Girl Can’t Help It, Jamboree and Shake, Rattle and Roll.

Crossover prodigy

In many ways Domino was a perfect crossover artist. His life and his music brought together many different strands in American culture. He was born of French Creole parentage on February 26 1928 in New Orleans, a city he celebrated in songs such as Walking to New Orleans and where he lived the vast majority of his life. He even survived Hurricane Katrina in 2005, when he had to be rescued by helicopter from the roof of his ruined home in the Lower Ninth Ward. He lost all his possessions in the flooding, including his National Medal of Arts, which was later replaced by President George W Bush.

Domino was something of a child piano prodigy. He played local gigs from the age of 10, building up a solid local reputation before he signed to Imperial Records in late 1949 and began his incredibly productive relationship with Bartholomew. Stylistically, he was influenced by the rampaging boogie-woogie piano stylings of Albert Ammons and Amos Milburn, but he softened his sound with more ornate flourishes borrowed from Crescent City jazz legend Professor Longhair.

Trailblazer: Fats Domino helped break down racial divides in American pop music. Klaus Hiltscher via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA

Similarly, the powerful horns that drove forward many of Domino’s finest tracks, often with saxophonist Lee Allen at the helm, were set against warm, honey-dew vocals that never quite lost their supple Creole intonation. He was also adept at reworking mainstream pop idioms (listen to Valley of Tears from 1957) and an enormous fan of country music. When he took Hank Williams’s Jambalaya (On The Bayou) into the pop charts in 1962, the hybrid seemed to make perfect sense.

By 1962, however, Domino’s glory years were already behind him. Like many of his fellow rock and roll pioneers, he struggled to meet the challenge posed by a whole host of anodyne teen idols in the early 1960s and then with the aftermath of the British invasion spearheaded by the Beatles in 1964. Yet his influence endured. The first record George Harrison ever bought was Domino’s 1956 pop and rhythm and blues crossover hit I’m In Love Again. In 1968, the Beatles’s Lady Madonna was essentially Paul McCartney’s homage to Domino’s seminal 1950s work.

In 1975, Ain’t that a Shame reappeared on John Lennon’s Rock’n’Roll album, just as it had in the 1973 hit film American Graffiti, George Lucas’s love letter to the teenage America of the late 1950s and early 1960s. It was an era to which Domino’s music provided a joyous soundtrack, while creating a musical legacy that ultimately transcends time and place.

As Britain’s poet laureate Carol Ann Duffy put it in her 2003 tribute to the singer: “Dominus, dominum, domine, Domino!”