Eighty-five percent of minority female attorneys in the U.S. will quit large firms within seven years of starting their practice.

BY LIANE JACKSON

ABA Journal, March 1, 2016 —

Photo Illustrations by Stephen Webster

Occasionally when Jenny Jones walks down the hall of her white-shoe law firm, a chairman emeritus will stop and ask how she’s doing and about her work. These moments are a highlight because outside of this intermittent interaction, Jones feels largely ignored by the powers that be.

Idling in her career, unable to hit the billable-hour requirements, Jones (her real name is not used due to the sensitivity of the issue) is a fifth-year associate busy planning an exit strategy. But hers is not an isolated tale of personal failure; it is the all-too-common story of women of color struggling to thrive at large law firms—and leaving in droves.

Statistically, Jones faces a grim career outlook. Eighty-five percent of minority female attorneys in the U.S. will quit large firms within seven years of starting their practice. According to the research and personal stories these women share, it’s not because they want to leave, or because they “can’t cut it.” It’s because they feel they have no choice.

“When you find ways to exclude and make people feel invisible in their environment, it’s hostile,” Jones says. “Women face these silent hostilities in ways that men will never have to. It’s very silent, very subtle and you, as a woman of color—people will say you’re too sensitive. So you learn not to say anything because you know that could be a complete career killer. You make it as well as you can until you decide to leave.”

Disturbing sentiments like these led the ABA Commission on Women in the Profession to undertake the Women of Color Research Initiative in 2003. Findings concluded that, in both law firms and corporate legal departments, women of color receive less compensation than men and white women; are denied equal access to significant assignments, mentoring and sponsorship opportunities; receive fewer promotions; and have the highest rate of attrition.

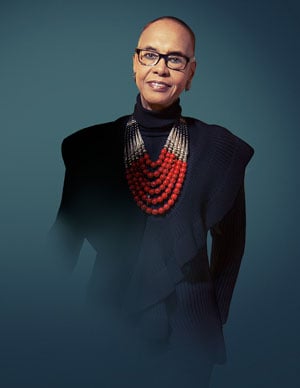

“If you look at the women-of-color research, the numbers are abysmal,” says the New York Public Library’s general counsel, Michele Mayes, who chairs the ABA commission. “When you lose any ground, you lose a lot because you never had that much in the first place.”

Studies and surveys by groups such as the ABA and the National Association of Women Lawyers show that law firms have made limited progress in promoting female lawyers over the course of decades, and women of color are at the bottom.

“We’re still a profession less diverse than doctors or engineers and that is 88 percent white,” notes Danielle Holley-Walker, dean of Howard University School of Law. “We’ve been at this for 40-plus years—firms have been recruiting lawyers of color since the late ’60s.

“There should be no mystery about how you create a diverse workforce. It’s just a commitment,” Holley-Walker says. “There’s a refusal to acknowledge that meritocracy goes hand in hand with diversity. But we have to have a group of lawyers that are both excellent and diverse.”

Michele Mayes. Photograph by Len Irish.

DECADES OF PIPELINE

The trajectory of women of color entering BigLaw dovetails with the progress of women entering the profession over time.

In the 1980s, as chair of the ABA’s newly formed women’s commission, Hillary Clinton signed off on the first-ever ABA report on the status of women in the profession. The prescient, but dire, conclusion? That the passage of time and the increase of women in the field would not erase the barriers to practice or solve problems that female lawyers face.

“That was the mid-’80s,” observes Laurel Bellows, co-chair of the ABA Task Force on Gender Equity and principal at the Bellows Law Group in Chicago. “When I chaired the commission six to eight years later, we came up with another report, and the conclusion was the same.”

According to the National Association of Women Lawyers, since the mid-1980s, more than 40 percent of law school graduates have been women. But despite a decades-old pipeline of female grads, there remains a disproportionately low number of women who stay in BigLaw, and even fewer who advance to the highest ranks. The ninth annual NAWL survey, released in 2015, shows that women account for only 18 percent of equity partners in the Am Law 200 and earn 80 percent of what their male counterparts do for comparable work, hours and revenue generation.

“We have a pay gap in our own profession,” Bellows says. “And let’s remember, 80 percent is very significant when you’re talking about equity partners because that could mean millions of dollars in terms of retirement.”

Data released last year by the National Association for Law Placement show the overall percentage of female associates decreased over most of the previous five years, although women and minorities continue to make marginal gains in representation among law firm partners.

Buoyed by increases in Asian-American and Hispanic women on staff, the percentage of minority female associates rose from about 11 percent between 2009 and 2012 to 11.78 percent in 2015. And those in the trenches say snapshot statistics don’t tell the full story. For example, NALP also reports that representation of African-American associates in the profession has been declining every year since 2009—from 4.66 percent to 3.95 percent.

And according to a November NALP press release, at just 2.55 percent of partners in 2015, minority women “continue to be the most dramatically underrepresented group at the partnership level, a pattern that holds across all firm sizes and most jurisdictions.”

Tiffany Harper recently transitioned from law firm life to a post as associate counsel for Grant Thornton in Chicago; she also co-founded Uncolorblind, a diversity blog and consulting company. Previously, she worked in corporate bankruptcy and restructuring at Schiff Hardin and, most recently, Polsinelli. Harper saw an in-house position as a chance to broaden her skill set, but she says she also saw the writing on the wall.

“I didn’t see a path for me to partnership at a large law firm. For women of color, there has to be a synergy for you to make partner,” says Harper, who has also served as president of the Black Women Lawyers’ Association of Greater Chicago. “You have to have everything working in your favor at the time you go up for a vote: a practice group that is thriving, the billable hours, people singing your praises, a client base. That has to all come together for you in a way it doesn’t have to for other people.”

Greenspoon Marder shareholder Evett Simmons knows all too well how tough it can get. Based on the statistics, she’s already an outlier. She joined a Florida law firm as a lateral equity partner in 2000 that was later partially absorbed by Greenspoon Marder, where she is currently the only female shareholder of color.

Evett Simmons. Photograph by Doug Scaletta.

Simmons grew up in the Jim Crow South, where as part of the demoralizing impact of segregation, she “didn’t believe black folks were as good as white folks.” That is, until she got to college and was the student frequently tapped to help white students complete their term papers. From there, Simmons continued to expand her horizons, attending law school and eventually rising to partner and chief diversity officer at Greenspoon Marder.

“I started at a time when it was difficult for women to get positions, let alone African-American women,” Simmons notes. “I started with legal services, went to a small firm, opened up my own firm, merged with another firm.”

With 33 years of practice under her belt, Simmons has seen the effort it takes for minority lawyers to succeed. In many ways, it’s a numbers game.

“My focus has been the pipeline,” she says, with the goal of expanding the existing pool of minority female law grads. To that end, Simmons started a law camp with the National Bar Association, based at Howard University. Some camp graduates are now practicing lawyers. But that’s just the first step.

“We need to make sure they have business and are fairly treated,” Simmons says. “This is the next phase in my work with the ABA.”

Like many working on recruitment and retention issues, Simmons recognizes that getting minority female candidates in the door isn’t the same as keeping them there. And each ethnic group faces its own challenges.

In the first study of its kind, the National Native American Bar Association found that Native Americans often feel invisible and are “systematically excluded from the legal profession.” The NNABA study, The Pursuit of Inclusion, found that “diversity and inclusion initiatives have largely ignored the issues and concerns of Native American attorneys.” Not surprisingly, women were more likely than men to report demeaning comments, harassment and discrimination based on gender.

“We can’t talk about diversity generically; we have to talk about women of color specifically in order to make a difference,” says Arin Reeves, president of the Chicago-based consulting firm Nextions, who studies unconscious bias and has pioneered research on women of color at large law firms and in corporate America. “Most gender strategies affect the majority of people in that gender category, which are white women,” Reeves says. “Racial and ethnic strategies are created around biases involving minority men. But women of color have the highest attrition rate. This is a group impacted by both gender and racial bias, so they will be impacted at twice the rates.”

NOT JUST A U.S. PROBLEM

As the only black female attorney in a 200-lawyer office of a multi-national firm based in Toronto, fifth-year associate Indi Smith (her real name is not used due to the sensitivity of the issue) faces a stark reality. The lack of diversity coupled with a macho firm culture has left her feeling isolated and demoralized.

At her firm, common interests like hockey—a sport she doesn’t follow—are crucial for relationship building. Instead of continuing to fight an uphill career battle, Smith is exploring her options. She calls her experience at the firm “unhealthy” and says it has drastically affected her self-confidence.

“In order to advance you need to get work, show your progress in terms of complexity of the work—but it’s an environment where you only get work based on the relationships with partners,” Smith says. “There’s no one here who I can commiserate with or who is a source of work for me. Just being able to see someone who looks like you would help.”

Smith says her request to join her firm’s diversity committee was rejected, and the lip service given to more inclusion hasn’t translated into action. But she notes that even if there were more attorneys of color on board, hiring diverse attorneys isn’t enough without creating a culture of inclusiveness.

“A lot of law firms have jumped on the diversity and inclusion bandwagon, but none of them are really diverse in a way that truly matters,” Smith says.

The Law Society of Upper Canada is trying to bring more attention to issues of diversity and equity in the profession through a working group and reports such as Challenges Faced by Racialized Licensees. A number of survey respondents told LSUC researchers they were forced to enter solo practice because of barriers faced in obtaining employment or because they were unable to advance in other practice environments. According to one anonymous respondent:

“Most of us are sole practitioners because we could not get into large firms because of racial barriers; the ones I know who got into firms ended up leaving because of feelings of discrimination, and ostracizing and alienation [such as] not being invited to firm dinners and outings. Some black lawyers feel suicidal because of repeatedly running into racial barriers—not academic performance—trying to enter large firms.”

Jones, who is also a Toronto-based attorney—can commiserate, although she was one of a lucky few to receive an offer from an elite firm out of law school. Still, as one of the only women of color at her office, her experience over the years has not been positive.

“We’ve had so many great female associates leave, and I don’t see anyone on the path to become a partner—black, white, you name it,” Jones says. “I don’t see women being placed into positions where they can become rainmakers,” she says. “Unless you have a really good champion, a white male who will protect you in a certain way, it’s a tough fight. It’s a losing battle. If you want to make it to partnership, it’s at what cost? And then when you make it to partner, what are you going to do then?”

DEFEATING DEFEATISM

Helping law firms understand how they can support the careers of women of color is Reeves’ focus. She says partners need to ask themselves very specific questions about their actions in the diversity realm and determine whether their efforts are truly proactive. Instead of succumbing to a defeatist perspective, the question should be “How can we fix this?” not “Can it be fixed?”

“People think because they’re committed to diversity and inclusion that they are creating diversity and inclusion. But partners need to ask themselves: How am I mentoring women of color and how can I do so?” says Reeves, a former lawyer who has a doctorate in sociology.

Latina attorney Gray Mateo-Harris says that after eight years practicing labor and employment defense, she’s finally found a firm focused on growing diversity and the unique needs of attorneys who are women of color. Mateo-Harris says Ogletree, Deakins, Nash, Smoak & Stewart in Chicago has provided an environment where she can thrive and find balance.

“You don’t realize early in your career how critical it is to have the support that will develop you as an attorney and help your career blossom,” Mateo-Harris says. “The reality is, as a woman of color I can’t necessarily count on inheriting a partner’s book of business. That’s not usually an option for people of color—and especially women.”

Mateo-Harris has worked at a smaller firm and in BigLaw and notes that too often, minority women are lost in the shuffle of incoming classes, left to sink or swim.

“You really need to be at a firm where the culture sees attorneys as an asset to be invested in, not as fungible,” she says. “It doesn’t bode well for women of color to be thrown in and see if someone takes an interest in them and mentors them. Those chances don’t usually end up favorably for women of color.”

To help women of color navigate the law firm dynamic, the ABA Commission on Women in the Profession published a brochure in 2008, From Visible Invisibility to Visibly Successful, which offers success strategies based on advice gathered from dozens of female minority partners.

“It takes a village to raise a lawyer” was one insight provided by a study participant, explaining how she learned to find a support system outside of the firm in addition to one within.

Another partner described how she hired a coach to give her business development training in order to grow her book of business.

“Success in law firms is one part intellect and four parts stamina,” said another respondent, warning that the challenges of isolation and racial and gender bias could take a physical and mental toll.

Arin Reeves. Photograph by Wayne Slezak.

“There’s a lot to be said for going in knowing you’re going to be treated differently, so I need to work twice as hard,” Reeves advises. “Understand that it’s not in your head. It is real, it is happening and it’s not easy.”

She adds: “Most women of color at law firms have phenomenal survival strategies, but we think it’s going to be fair and we kind of get sideswiped. But if you’re well-prepared for it, then I think you’re steady on your feet and no one can shake you with craziness.”

The 2008 report, which was prepared by Reeves, also urges young attorneys to “show up” and “speak up” at social events and meetings, and notes that even if you’re shy or don’t like to schmooze, you should actively seek out mentors inside and outside your law firm by joining organizations and networking.

And law firm mentors need to be “situated in the sphere of influence within the firm.” Several contributors stressed that mentoring is crucial to developing a client base and more critical to a lawyer’s success and mobility than the number of billable hours one generates.

Many successful female attorneys, including Simmons of Greenspoon Marder, talk about the male partners and mentors who were advocates and allies and helped their careers advance. Bringing men to the table and capturing the attention and stories of men who “get it” is often cited as essential to continued progress.

Holley-Walker, the Howard law dean who enjoyed a successful career in commercial litigation at a large law firm before going into academia, says young lawyers must get good work and continue to get better work as they progress in their practice. And that means having influential partners at the firm take an interest in their career, which isn’t often the case for women of color.

“That move from mentorship to sponsorship” is key, says Holley-Walker. “People who will know your work intricately and give you honest feedback—and when it comes time, will basically go to bat for you.”

To encourage partners to become mentors and sponsors, the brochure concludes that practice group leaders need to be held accountable for ensuring that work is distributed in an equitable and unbiased way. Associates are judged on their ability to get assignments from partners, but partners aren’t held accountable or required to work with a variety of associates. That puts the most vulnerable attorneys at risk for failure.

CHANGING THE PARADIGM

Simmons believes a climate of inclusiveness for women and minorities, where differences are acknowledged and valued, can only occur once firms change the entrenched paradigm on delivery and individual contributions.

“We need to be able to recognize that a woman has some value other than getting a book of business. Maybe she can assist you with managing a book of business,” Simmons says. “We need to measure success on more than whether a person brought a client into the room. There are other intrinsic values that can grow the firm besides bringing in money.” These tangible benefits to the firm’s business can include client services and committee work, Simmons says.

As law firms reassess their business models under the “new normal” of law practice, many hope external change will open up paths for minority female attorneys to succeed.

“The billable hour was the altar at which [law firms] prayed,” says Mayes, the women’s commission chair. “That altar is being seriously challenged. As a young person looking at the profession, many would say, ‘My investment ain’t that great here.’ Too many lawyers in the job market, not enough return on investment.”

Mayes points to other industries that have changed their profit-sharing and partnership models to be more inclusive and to reflect the times. “If you look at Deloitte or KPMG, they’ve gotten better at cultivating talent and not just having one way to do it. It’s more of a team model than an individual model.”

Reeves says part of the problem is that firms measure, recognize and reward business development primarily based on how men develop business. According to a 2014 survey by the National Association of Women Lawyers, lack of business development and high attrition rates are the two main reasons the number of female equity partners has not significantly increased.

“They need to see you as profitable,” says Harper. “Either you have to have brought in smaller matters, RFPs, you’re in the community—how do you bring in dollars? It’s been too long that firms have not been able to make this work [for women of color]. I think it will take a structural change, and I don’t know that firms are ready and willing to make a difference in how they do things.”

While little has changed in BigLaw as to how the pie is divvied up or how assignments are passed out, Reeves points out that the law doesn’t pivot fast. “The law generally has lagged be-hind its corporate counterparts, and it’s the most risk-averse profession,” she says. “Even with technology—law firms were the last to adopt email. When we keep all this in mind, we depersonalize the issue a little bit and we can actually pursue change with a little more stamina.

“I don’t think it’s that law firms see the problem and don’t want to do anything about it,” Reeves says. “It will change. It’s just going to take longer here than it does in other places.”

This article originally appeared in the March 2016 issue of the ABA Journal with this headline: “Invisible then Gone: Minority women are disappearing from BigLaw—and here’s why.”

____________________________________________________________________________________

Sidebar

Learning—& Winning

Law firms tend to be opaque operations, with limited details available on pay, policies and perks. But if you’re a female attorney looking to lateral or a female law student on interview rounds, there is a resource that offers a window into what you can expect from BigLaw.

The annual list of the 50 best law firms for women from Working Mother Media and Flex-Time Lawyers showcases what some of the top firms are doing to attract and retain female talent. Law firms that make the cut are recognized for their family-friendly policies along with career and business development initiatives. Making the list is a competitive process the founders view as an instrument of change. The firms “learn lessons about themselves,” says Jennifer Owens, editorial director of Working Mother magazine and director of the Working Mother Research Institute. “The initiative was founded for the competition, but also for the learning. The act of filling out [the application] is learning. We hope the carrot is: You’re trying to get on this list where we’ll laud you as a best law firm for women.”

Participation in the survey is free and voluntary. Firms complete an extensive, confidential questionnaire and receive a scorecard that shows how they rank alongside other participants. Additional reports with in-depth analysis of the results are available for purchase. And the winners’ list is disseminated to general counsel and law schools across the country.

Drinker Biddle & Reath has made the 50-best list four times. Partner Lynne Anderson is proud of the firm’s recognition and focus on women’s initiatives, which she says requires intention and support from the top. “I think any firm has to have more than just the trappings,” Anderson says. “They have to have a roll-up-your-sleeves commitment to the advancement of women in the firm. That takes financial commitment, time commitment—including from the senior levels of the firm.”

Anderson says some of the policies and programs that helped propel Drinker Biddle onto the list include compensation transparency, a 12-week paid parental leave policy, flex-time and reduced-hours work options, and a strong women’s leadership committee that includes the firm chairman.

“What does it take to have a firm that’s supportive of women? It’s not just helicoptering in and out of the issue. It’s sustained and ongoing programs—a committee, a budget and policies that make this work,” Anderson says. “And to be willing to take a hard look at the metrics on a regular basis.”

Top firms on the 2015 list employ more female equity partners than the national average—20 percent vs. 17 percent. And 96 percent allow reduced-hour lawyers to be eligible for equity partnership promotion. Other elements taken into account include compensation, pro bono work, benefits, flex-time options, paid leave and workplace culture. The list also looks at the rates of women of color in leadership roles.

The 50-best list was founded in 2007 by Flex-Time Lawyers’ Deborah Epstein Henry in partnership with Working Mother Media. According to Henry, the best law firms are those that focus both on retention and promotion, by cultivating and investing in female talent. “I think a lot of women’s initiatives make the mistake of not understanding the link between work-life issues and power and leadership. They think they have to advocate for one or the other,” Henry says. “We have the philosophy that if you don’t support women in their early years, we’re never going to have the critical mass of women we need in order to fill leadership roles like equity partner.”

Liane Jackson is a lawyer and freelance writer based in Chicago.