By Karen Grigsby Bates

NPR, April 19, 2018 —

The current furor over the Brooklyn Museum’s appointment of a white woman to oversee the museum’s African art collection is not surprising or infuriating to Steven Nelson. Nelson is an African-American art historian at UCLA who specializes in African art, and he says, “There are very few of us in the field.”

Despite the public assumption that most African art curators in the U.S. are of African descent, Nelson points out, “in the United States, the field is largely made up of white people — and most of those people are female.” So the appointment of Kristen Windmuller-Luna was, for Nelson, business as usual.

Protesters in front of the Brooklyn Museum (image via @kino___eye)

But some Brooklynites are pushing back. A coalition of community activist organizations, Decolonize This Place, sent a strongly worded open letter to the museum. The group urged management to rethink Windmuller-Luna’s hiring, saying, “No matter how one parses it, the appointment is simply not a good look in this day and age, especially on the part of a museum that prides itself on its relationships with the diverse communities of Brooklyn.”

The museum, which is acknowledged to have a more diverse staff than most, responded via director Anne Pasternak: “I am writing to state unequivocally that the Brooklyn Museum stands by our appointment of Dr. Kristen Windmuller-Luna.” Pasternak noted the museum’s collection of African Arts “is among the most important and extensive in the nation” and the new curator was chosen for her deep knowledge and love of the field.Gatekeepers of a different culture

No one is debating Windmuller-Luna’s qualifications (her degrees from Yale and Princeton, and previous museum appointments). They are registering frustration that white people are continually made to be gatekeepers of art from the African diaspora.

“You know,” UCLA’s Steven Nelson continues, “they made two hires, and no one seems upset about the fact that they hired a white guy for photography, which in fact is a much more diverse field than African art.” What people should really be up in arms about, Nelson says, is the fact that “there were eight reasonably high-profile hires in the art world over the last couple of weeks, and that seven of those eight are white people.” (One is Asian-American.) “No one batted an eye about that,” he says.

For instance, Colin Mackenzie was hired to oversee the Art Institute of Chicago’s extensive Chinese art collection. And on Tuesday, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, arguably the most prestigious U.S. museum, announced the appointment of a new director, Max Hollein, who is white, male and European.

Former Met director Philippe de Montebello (also white, male, European) dismissed a group request to deliberately search for a female director in one word: “Ridiculous.” Two days after Hollein’s appointment was announced, Liza Oliver, a former Fellow of the museum, and current art history professor at Wellesley College, published a tart opinion piece in The New York Times: “Appointing Yet Another White, Male Director Is a Missed Opportunity for the Met.”

Non-diversity a systemic problem for most museums

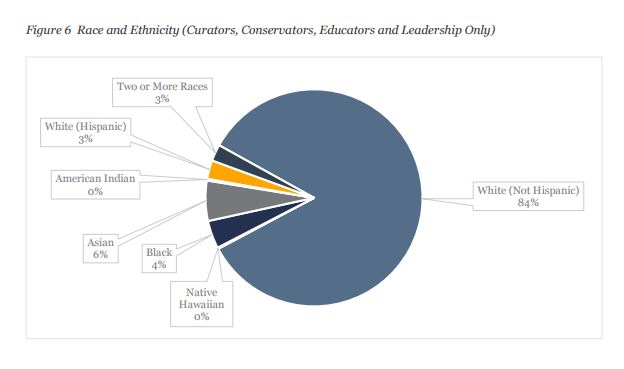

The Mellon Foundation study reveals that leadership positions are largely occupied by white staffers.

In 2015, the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation supported a survey to gauge ethnic and gender diversity among the country’s museums. The results were dismaying: according to the survey, 84 percent of the country’s museum staff (curators, educators, conservators and upper-level administrators) was non-Hispanic white; blacks were 4 percent, Asian Americans 6 percent. Native Hawaiians and Native Americans? Zero.

Women fared better — at almost 60 percent of professional museum staff. Significant numbers of nonwhite staff tended to be in jobs like security, human resources, facilities and finance.

Some critics say the lack of people of color in the museum world is a systemic problem that has long needed to be addressed. “As a discipline, art history has been very poor in attracting a diverse group of people interested not only in African art, but in all fields,” UCLA’s Nelson says. He adds that encouraging the interest in art careers has to start in high school and college.

Removing barriers to entry

Part of the problem is certainly economic. Internships in galleries and museums often give young people a coveted foot in the door of their intended careers. Those jobs may be prestigious, but they don’t pay much. (Some don’t pay anything.) Like internships in publishing, the movie and television industries, and in talent agencies, the steady stream of interns tends to come from young people who have some financial support other beyond their salaries. Those who have to work to help pay college expenses may have to pass up an internship in the arts, no matter how avidly interested they are in the field.

Nelson himself remembers turning down an internship he wanted because he couldn’t afford to take it.

So priming the pump to get more people of color into the arts career pipeline is an important part of the solution, one in which museums may have to lend a hand if they want to see a diverse staff. In 2013, Mellon gave a $2.07 million grant to five large museums, including the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Atlanta’s High Museum of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. The grant funded curatorial fellowships for undergrads and was designed, in the foundation’s words, “to open up the museum as a potential workplace to students from historically underrepresented minorities and other undergraduates who are committed to diversifying our cultural organizations.”

If museums are going to last through the 21st century and beyond, it’s critical that they reflect the diversity of the world outside their doors. Museum leaders are aware of this, and have begun looking for ways for their institutions to survive and thrive. One effort was a Mellon-funded series of case studies, done in collaboration with the Association of Art Museum Directors, which chose eight museums that have managed to encourage diversity, equity and inclusion. Five case studies have been released; three will be released at a later date. The point is to show what these museums have done to diversify, in the hope that others will be encouraged to follow suit.

Brooklyn Museum, New York City Jupiterimages / Getty Images

Whose museum?

The Brooklyn Museum is one of the eight surveyed. It’s facing the same challenges as the other museums, and a more immediate one: as the neighborhoods around it become ever more gentrified, the Brooklyn Museum will have to decide not only how to accommodate the newer, more affluent arrivals, but how to continue to serve the more economically marginalized communities that were there before.

Part of the ire over Kristen Windmuller-Luna’s appointment seems to be related to anxiety on the part of many in black and brown Brooklyn: that their presence is much less relevant than it once was. That’s painful for many black Brooklynites; Brooklyn was often considered the Black Mecca, the cultural center of greater New York’s African diaspora. (It’s where, for instance, millions carouse up Eastern Parkway every Labor Day at the West Indian Day Parade.)

“I remember the 1990s and 2000s when (the museum) catered to a more working-class community,” Imani Henry told the blog Hyperallergic. Henry works with Equality for Flatbush, one of several groups involved in trying to slow the pace of gentrification. “The programming felt much more in touch with what was going on in the community.”

Henry said that while children’s events a decade ago were majority black, that’s no longer the case. He feels the museum has become gentrified to reflect the affluence in the surrounding neighborhoods.

Imani Henry is not objecting to Kristen Windmuller-Luna because of her ethnicity, he told Hyperallergic. “We’re not saying we don’t want a white woman, but we want someone with a commitment to communities.”

By that, Henry means all the communities the museum was designed to serve: the newly arrived owners of fine brownstones and luxe condos. And certainly the families living in less-elegant neighborhoods, who also want to continue to feel the museum belongs to them, too.