By Yuki Noguchi

NPR All Things Considered, May 30, 2017 —

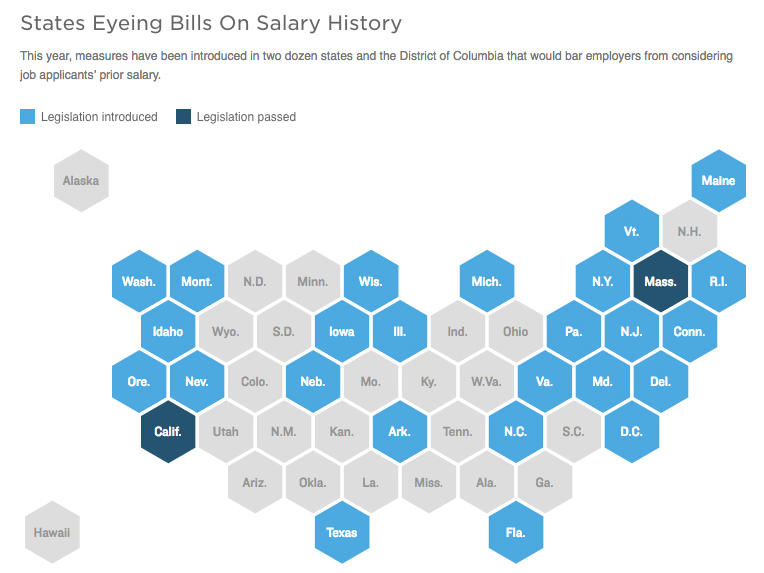

This year, 25 states and the District of Columbia are considering measures that would bar employers from asking job candidates about their prior salary. Last year, two states — California and Massachusetts — adopted similar policies, aimed at trying to narrow the pay gap for women and minorities.

Such measures are designed to help people like Aileen Rizo. She was four years into her job as a math teaching consultant for Fresno County, Calif., when she found out, in 2012, that a new male hire with less education and experience was offered a salary roughly 20 percent more than she was making.

Rizo was stunned.

Aileen Rizo sued her employer after learning that a new male hire with less education and experience than her was offered about 20 percent more than she was making. (Tomas Ovalle)

“I kind of knew that I had broken stereotypes, as a mathematician, and as the only full-time woman in that department,” as well as being a Latina minority, she says. “But then to find out that you’re getting paid less than all of your male counterparts — that they all started much higher salary steps then you did — is just … devastating.”

Rizo complained to human resources, assuming the problem would be ironed out. Instead, she was told her salary was set based on previous pay — and that her salary would not be adjusted. She says she was shocked and felt locked in.

“I couldn’t educate myself out of being paid less, I couldn’t get more experience or be in the job market longer to break that cycle,” she says. “Because low wages will follow you wherever you go as long as someone keeps asking you how much you were paid.”

Notes — Under measures passed in California and proposed in Arkansas, an employer being sued for discrimination can’t justify a pay discrepancy based solely on salary history. Legislation introduced in California would ban employers from asking for job applicants’ salary history. In addition, a number of cities and Puerto Rico have enacted measures banning salary-history questions. Source: American Association of University Women Credit: Brittany Mayes/NPR

Rizo filed suit, arguing her employer violated the Equal Pay Act, the 1963 law aimed at abolishing wage discrimination based on gender.

“I have three young daughters, and I don’t want them ever to feel that way,” she says, her voice cracking.

Rizo prevailed in lower court, but last month the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals overturned that ruling. Now, she’s considering an appeal to the Supreme Court.

“After the 9th Circuit decision, I felt like now it’s black and white … you can pay a woman less,” she says. “I don’t want that to be the end of the story.”

In the years since Rizo filed her case, states and cities have been passing laws banning employers from asking about previous salaries. Last year, Massachusetts and California became the first states to do so. New York City adopted a similar law, and Philadelphia’s ordinance is temporarily stayed pending litigation.

Most of the measures have yet to take effect, so there is no data to show what effect they’ve had.

“The problem with proving the efficacy of public policy that hasn’t been tried before is that it hasn’t been tried before so no one can research it,” says Kevin Miller, a researcher at the American Association of University Women. In a 2013 report looking at Department of Education data, his group found that women make 7 percent less than men a year out of college, even after controlling for variables such education, college major, occupation, industry and hours worked.

Miller says that gap tends to compound with age, and is bigger for minorities — although the disparity is less where salaries are set by union or government rules.

“When you have more room to maneuver and more room to negotiate, I think that’s where you see bias come in,” he says.

Rizo’s case prompted congressional delegate Eleanor Holmes Norton, D-D.C., to introduce federal legislation banning employers from asking about prior salary information. She points to data that show even highly professional women such as doctors and lawyers start out earning less.

“That means, for the rest of their career, they will carry a lower wage,” she says.

Norton says her bill has support from only Democrats, but she’s hoping to build broader support over time.

[NWLC Resources: Wage Gap by State for Asian Women, Black Women, Latinas, Native Women . .]

“We don’t sit here and say, ‘Look at the current Congress, why put this bill in?” she says. “We do the opposite. I ask you to look at what you think the next Congress is going to look like.”

But employer groups say a patchwork of different laws add to administrative burdens.

Nancy Hammer, government affairs counsel for the Society for Human Resource Management, says many employers ask about prior salary, but not in order to discriminate.

“They don’t want to waste the time of a candidate who’s seeking a higher salary than they can offer,” she says.

Hammer argues that instead of a ban on salary history, policy should focus on encouraging businesses to identify and fix any internal pay gaps — in exchange for legal protection from pay discrimination suits.

“Right now, employers are hesitant to do that because it raises alarm bells that they were doing something wrong all along,” she says.

Employers want to keep their workers happy and motivated, Hammer argues, so it’s in their interest not to create disparities in pay. And she says many are willing to take a hard look at whether it’s necessary to look at a person’s past salary.