The Brookings Institute

By Ryan Nunn, Policy Director – The Hamilton Project Fellow – Ecomic Studies

Jana Parsons, Research Analyst – The Hamilton Project

Jay Shambaugh, Senior Fellow – The Hamilton Project – Economic Studies

This article was initially posted at The Brookings Institute.

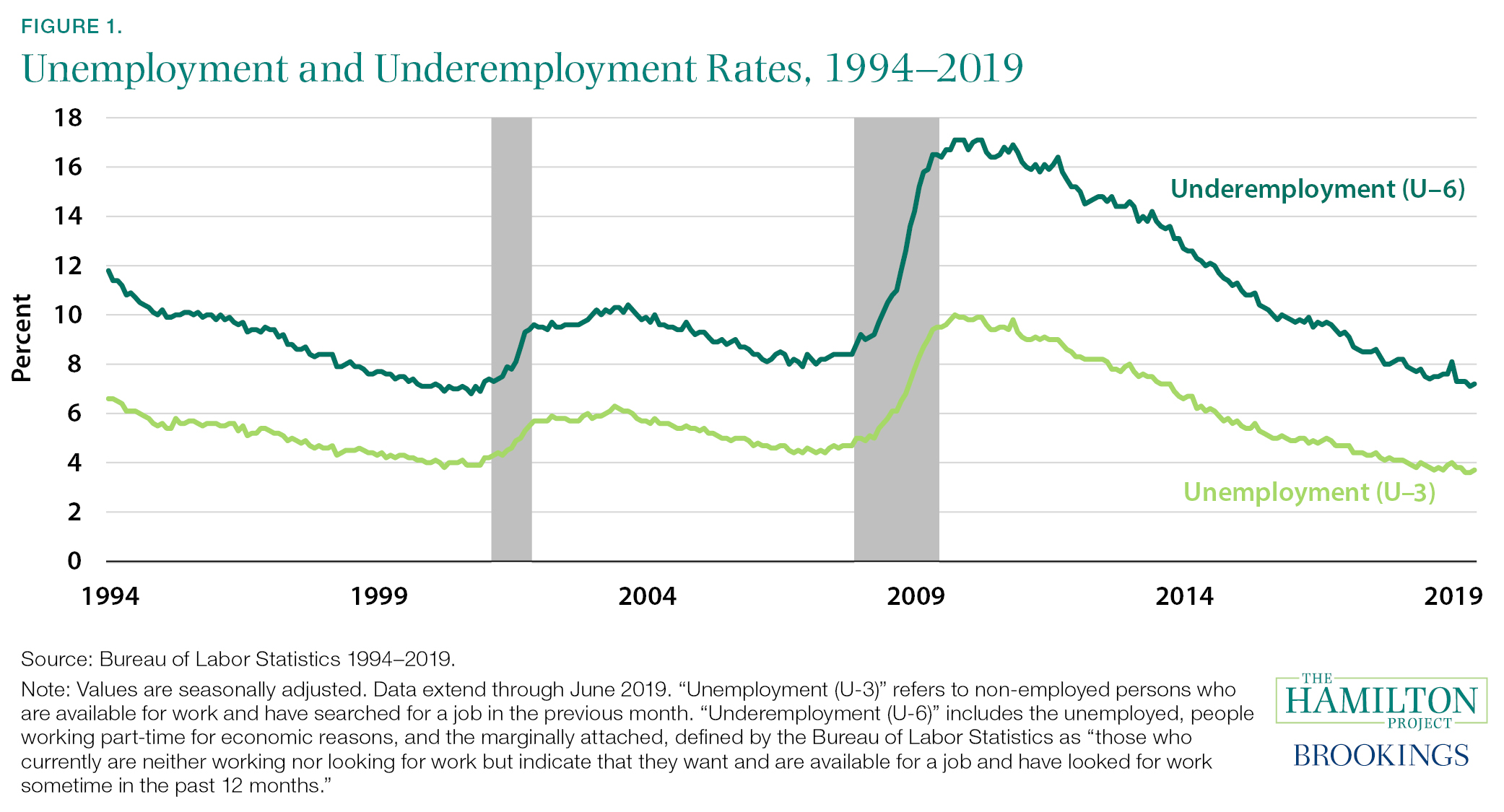

Each month a new reading of the unemployment rate helps us assess the health of the labor market. However, as many have pointedout, the unemployment rate is in some ways a narrow measure of the labor market that misses important aspects of labor market distress.

A broader indicator of labor market weakness called the underemployment rate—and in Bureau of Labor Statistics jargon referred to as the U-6 unemployment rate—takes into account some of this additional distress.

Examining both unemployment and underemployment is useful for analyzing different aspects of the labor market, and, as shown below, it can reveal dramatic racial disparities.

In addition to the number of unemployed (those without a job and actively seeking work), the underemployment rate captures the number of people who work part time but would rather have a full-time job (called “part time for economic reasons”) and those who want and can take a job but have not looked for work in the past four weeks (called “marginally attached”). These groups make sense to include in a measure of underemployment because while they are not unemployed in the formal sense, they would work more if the option presented itself. While the unemployed are often those most ready to take new jobs, workers who are marginally attached and part time for economic reasons also stand ready to take full-time employment when employers are hiring.

At its peak in the wake of the Great Recession, the underemployment rate was 17.1 percent in October 2009, indicating that more than one in six people were experiencing some sort of labor market hardship (see figure 1). This was far above the 10.0 percent unemployment rate at the time and demonstrates the wide swath of individuals who were in labor market distress in the aftermath of the Great Recession. Since then the underemployment rate has steadily declined, and is now below its prerecession low, but it did not fall below its prerecession low for nearly a year after the unemployment rate did. In addition, at 7.2 percent in June 2019, the underemployment rate is nearly double the June 2019 unemployment rate of 3.7 percent. This makes clear that while a relatively small percentage of people are both out of work and currently searching for a job, there is still a considerable amount of underutilized labor and many people for whom the labor market is not providing adequate opportunities.

In 2010, after the Great Recession had officially ended, the average annual unemployment rate for black workers was 16.0 percent, compared to 12.5 and 8.7 percent for Hispanics and whites, respectively. The black unemployment rate is typically about twice as high as the white unemployment rate. Economists Cajner, Radler, Ratner, and Vidangos find that observable characteristics such as education, age, and marital status explain relatively little of the gap. Instead, black workers have a much higher risk of losing their jobs, accounting for much of the unemployment rate gap.

While unemployment rates have fallen substantially since 2010, racial disparities still exist today: in the first half of 2019 the unemployment rate was 6.6 percent for blacks, 4.4 percent for Hispanics, and 3.3 percent for whites. Moreover, as Andre Perry notes, national estimates of the unemployment rate mask the wide geographic differences in the labor market experiences of minorities.

Like the standard unemployment rate, the underemployment rate reveals very different labor market outcomes for black, Hispanic, and white workers (see figure 2). Below, we highlight a few of the distinct insights the underemployment rate provides about the varied labor market experiences of American workers.

- White workers have lower underemployment rates than black or Hispanic workers at all points in the business cycle. In fact, the peak white underemployment rate in the wake of the Great Recession was only slightly higher than the prerecession low for black underemployment.

- For black workers, the underemployment rate is strikingly high: black underemployment reached 24.9 percent in April 2011, well after the peak of the black unemployment rate at 16.8 percent in March 2010. That is, for more than a year after the black unemployment rate began to fall, the underemployment rate continued to rise.

- Hispanic underemployment rose more sharply—for both men and women—than white or black underemployment did during the Great Recession.

- The Hispanic underemployment rate rose 12 percentage points from December 2007 to December 2009, compared to 10 percentage points for blacks and just under 7 percentage points for whites.

- This was predominantly driven by increases in unemployment and the number of those working part time for economic reasons (i.e., those who would like full-time jobs but cannot find them) rather than changes in the number of marginally attached workers.

- Much of the gap between white and Hispanic involuntary part-time work can be explained by observable characteristics like education, industry, and occupation.

The large gaps in underemployment between white and non-white workers seen in figure 2 are driven by differing within-race gender gaps, as shown in figure 3. In December 2018, at 6.3 percentage points, the gap between black and white male underemployment is substantially larger than the 4.6 percentage point black–white gap for women. But the white–Hispanic gap is based on the opposite pattern: the underemployment gap for women (4.7 percentage points) is larger than the gap for men (2.8 percentage points).

The unemployment rate is an incredibly valuable summary statistic for the labor market. That statistic is effective in capturing changes in labor market conditions, making it a valuable basis for assessing cyclical patterns—particularly at the start of downturns. But as shown above, the unemployment rate misses the full extent of labor market distress. This omission is especially important during economic downturns and for black and Hispanic workers. The underemployment rate is also helpful for determining the amount of labor market slack that remains once the unemployment rate has fallen to a low level.

A focus on the unemployment rate alone would have suggested that the labor market experience of black workers was improving in 2010 when the underemployment measure showed deterioration, and an exclusive focus on unemployment would also have missed the particularly sharp deterioration of conditions for Hispanic workers in 2007–8. Examining patterns in underemployment is a partial remedy. However, the Bureau of Labor Statistics does not release a seasonally-adjusted monthly series for individual racial groups making underemployment rates less useful for real-time analysis to understand turning points in the business cycle. Still, much can be learned from these data to better understand how well the labor market is functioning for all workers.

Read the complete article at https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2019/08/01/race-and-underemployment-in-the-u-s-labor-market/