She became a global hate figure this year when she was outed as a ‘race faker’. Here, she talks about her puritanical Christian upbringing, the backlash that left her surviving on food stamps – and why she would still do the same again.

Rachel Dolezal at her home in Spokane. Photograph: Annie Kuster for the Guardian

By Chris McGreal

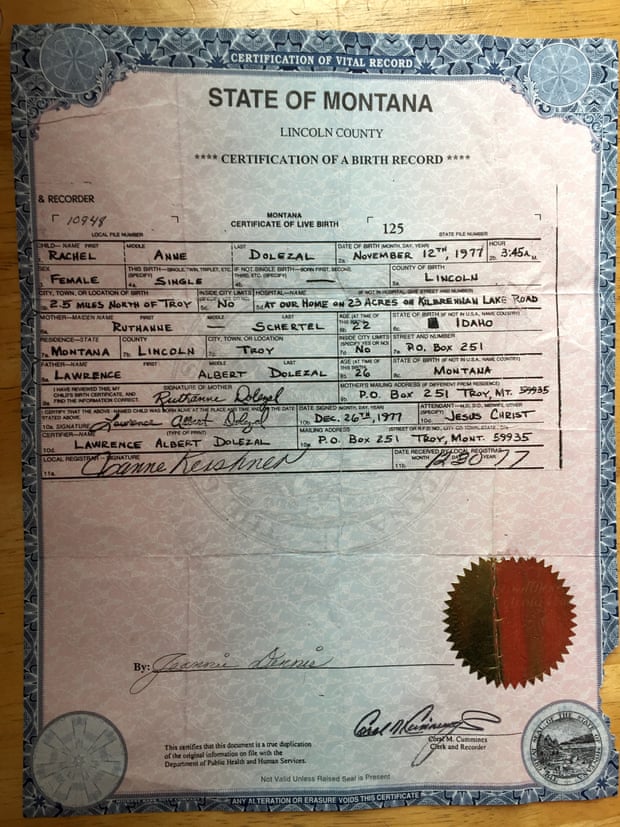

The Guardian, 12/13/15 — Anyone looking for clues to the real Rachel Dolezal would do well to begin with her birth certificate. In the bottom right-hand corner, under the names of the parents who brought her world crashing down by outing her as a white woman masquerading as black, is a box for the identity of the medic who delivered her as a baby. In it is written “Jesus Christ”.

Whether or not the son of God had a direct hand in her birth at home in rural Montana in 1977, he was ever present as Dolezal was raised by her fundamentalist Christian parents, Lawrence and Ruthanne. Life was dictated by the couple’s strict interpretation of the Bible, including a strong belief in creationism and a puritan-like commitment to simple living and harsh punishment.

Dolezal spent years imagining it was all a horrible mistake.

“I would have these imaginary scenarios in my mind where I was really a princess in Egypt and [my parents] kidnapped and adopted me. I had this thing about just making it through this childhood and then I’ll be OK,” she says.

As it turned out, Dolezal wasn’t an Egyptian princess, but she didn’t let go of the idea that maybe she wasn’t who her parents claimed she was. By the time she finally slipped from under the fundamentalist yoke years later, Dolezal was well on her way to becoming the person she regarded as her true self, a black American.

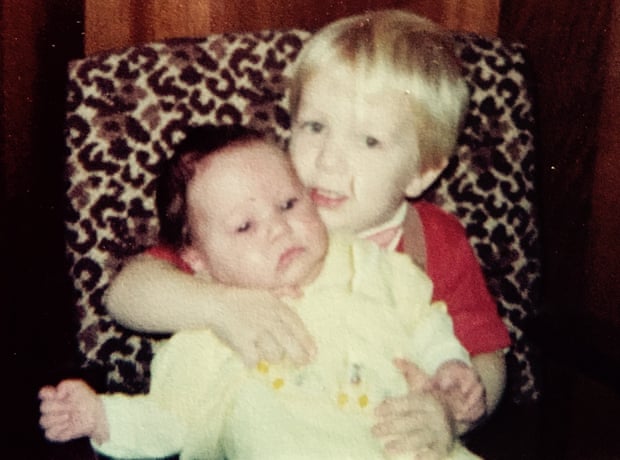

Dolezal as a baby. Photograph: Courtesy of Rachel Dolezal

In time, she changed her appearance, revised her history and constructed a new family. She adopted a series of African-American “dads” and presented to the world a black son, who turned out to be her brother.

t all came toppling down on 11 June this year, when she was asked in a television interview: “Are you African American?” Her stunned reply – saying she didn’t understand the question – was swiftly interpreted as evidence she was a “race faker”.

Some white people painted Dolezal as mentally unstable, on the grounds that no normal white person would choose to call themselves black. But it was the wave of rage and mockery from the African American community that really stung.

She was accused of exploiting the long history of black suffering to play the victim. The evident change in her appearance from a girl of European heritage to a woman with elaborate braided hair extensions and a distinct tint to her skin was portrayed as part of a long and insulting history of “blackface”.

Within days, Dolezal lost much of what she held dear, as the community she had championed for years turned on her. She was forced out as president of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Spokane and lost her African studies post at Eastern Washington University. Many of her friends now refuse to talk to her.

Dolezal as a baby, being held by Josh, her biological brother. Photograph: Courtesy of Rachel Dolezal

Dolezal cannot find a job – she has spurned “unsavoury” offers to do reality television and porn – and is reduced to raising her teenage son on food stamps with a bit of hairdressing on the side. She has a baby on the way.

I’m trying to regroup, rebuild, remember who I was before the frenzy. People telling me what to think, telling me what to do, telling me to go kill myself,” she says. “Locally, it feels like I am invisible. People don’t want to associate with me. This great leader that won all these awards no longer exists. It’s just like this disgust, and that was really hurtful, really hurtful.”

In the living room of her modest house in Spokane – still sporting the hair and skin tone, her “glow”, as she puts it, that so infuriated her critics – she weeps at what she regards as the injustice of the collective judgment against her. But Dolezal is not apologising for anything. She denies she lied to anyone. If people were confused, she says, it was because they didn’t ask the right questions. Above all, she remains firmly wedded to her insistence that she is black.

“For me, how I feel is more powerful than how I was born. I mean that not in the sense of having some easy way out. This has been a lifelong journey. This is not something that I cash in, cash out, change up, do at a convenience level or to freak people out or to make people happy,” she says. “If somebody asked me how I identify, I identify as black. Nothing about whiteness describes who I am.”

Rachel Dolezal in 1996 with her parents, Lawrence (left) and Ruthanne (right), her brother Joshua, and four young children the family had adopted. Photograph: Zuma/Rex Shutterstock

‘As long as I can remember, I saw myself as black’

As a child, Dolezal was defined by her parents’ religious fervour, right down to the homemade clothes. “We even spun the dog hair into yarn to make sweaters. We’d carve elk antlers into little buttons. I ended up being really embarrassed about the clothes we wore to school. In your lunchbox, it was elk tongue sandwich with homemade bread,” she says.

Punishment was routine, particularly for poor marks at school, according to Dolezal. “We all got bare bottom spankings. Bend down, touch your toes and get whipped with this board that they had,” she says.

Some of the Dolezal children were locked in a room with only a mattress and Bible, Dolezal says.

“I would cry myself to sleep at 13 because I felt like I didn’t have anywhere to go,” she says.

But even if Dolezal could not escape her family, she had started to believe that she was not of it.

“I’m sure it’s hard to make sense of for people from the outside, but for me it’s been like a consistent, organic process of coming into who I am. As long as I can remember, I saw myself as black. I was socially conditioned to discard that. It was an all-white town. I was very unhappy. I felt like I was constantly self-sabotaging in order to conform to religion, culture dynamics. I was censoring myself. I was shutting down inside,” she says.

Dolezal’s parents began adopting black babies – three from the US and one from Haiti. They claimed to have saved the children from being aborted.

Dolezal at a rally for immigration rights, earlier this year. Photograph: Courtesy of Rachel Dolezal

“I ended up having to sew cloth diapers for all the kids because we didn’t have money for diapers,” she says. “I felt like a mom to them. Feeding them, potty-training them.”

In the rush to explain Dolezal after she was splashed across the news in June, there was no shortage of people who made the connection between her adopted black siblings and the shift in her own identity, starting to braid first her hair and then that of her brothers and sisters, taking an interest in African American literature and history.

One of Dolezal’s first self-portraits, age five. Photograph: Courtesy of Rachel Dolezal

“I don’t think the siblings necessarily changed my identity,” she says. “I feel it was just an opportunity for me to open up more and it was more acceptable for me to go there, connecting, doing reading and the hair and all these things. It made sense to other people. Oh, your family adopted black siblings. That must be why you identify as black. Not really. The connecting piece for me, when I started to be able to bloom a bit more, was the adoptions gave me a reason to defend reading certain books.”

James Baldwin was high on the list. So were father and son John and Spencer Perkins, African-American religious leaders and civil rights activists in Jackson, Mississippi, who promoted community development around racial reconciliation. After finishing high school, Dolezal enrolled in Belhaven, a Christian college in Jackson, to be close to the Perkinses.

“It kind of had the two pieces. It had where I wanted to go and where I was coming from,” she says. “There’s the Christian piece there, because that’s good enough to make the parents feel comfortable with me going there. But it had more than what I had been raised with. It had connection to the black community, it had connection to community development and civil rights work and social justice work. That’s what I really wanted to do.”

Rachel Dolezal’s birth certificate, on which Jesus Christ is cited as being the medic in attendance. Photograph: Courtesy of Rachel Dolezal

She sought out Spencer as a mentor in college, where she studied art. But the relationship with the Perkinses soon went beyond academics. Before long, Dolezal had come to regard herself as part of the family. She said Spencer became “like a father figure”. His father, John, “became Grandpa Perkins” to her. She speaks of other members of the family as “Aunt Joanie, Uncle John”.

Jackson was largely segregated and Dolezal boarded with a couple, Sam and Donna Pollard, in a black neighbourhood. In June, Donna posted a Facebook message calling Dolezal a “beautiful young lady”.

“I remember hearing her heart through our conversations, about how she knew in her heart that she was supposed to be born black,” she wrote. “Her struggle was tear-jerking real. We cried together many times, while I listened trying to understand how she felt inside and even tried (through scripture) to convince her it was just a phase that she was going through.”

Pollard observed something else. “Rachel even referred to my husband as her dad and me [as] her mom. It was clear that wasn’t accurate. I was too young to have a daughter her age, but we had that connection,” she said. “I do not think that Rachel Dolezal was intentionally trying to be deceptive.”

Pollard was the first woman to braid Dolezal’s hair.

“People started responding to me differently,” Dolezal says. “Because it was Mississippi, white girls don’t do that. A lot of people started responding to me as if I was biologically biracial. I kind of let the chips fall where they may.”

Marriage to an African American husband followed and a move to Idaho. The couple had a son, Franklin. It was not a good match.

“My husband didn’t want me to wear any black hairstyles. Nicole Kidman was his standard of beauty,” she says. “He was continually: why are you reading black history? Why are you doing this?”

Dolezal leading a Black Lives Matter rally with students in 2014. Photograph: Courtesy of Rachel Dolezal

Dolezal’s decision to seek a divorce in 2004 precipitated the final split with the people she refuses to this day to call Mom and Dad, her real parents.

“I lost my entire family because God hates divorce,” she says. “My marriage was like round two of being confined, being told what to do. So when I got divorced, I started returning to myself and returning to styling my hair how I wanted to style my hair and doing other people’s hair as well. That was my personal, I won’t say coming out, but owning who I was. By 2006, I was identifying as black.”

Dolezal no longer left it to others to interpret who she was, but that required a lot of little bits of what she calls “creative nonfiction”.

“People were: is she black? Is she white? What is she? What are you mixed with?” she says. “Usually I’d say my dad is black because to say that neither one is black creates this really long conversation. I don’t know that person. I don’t feel like I owe them that long conversation. They’re going to be looking at me as if I’m crazy.”

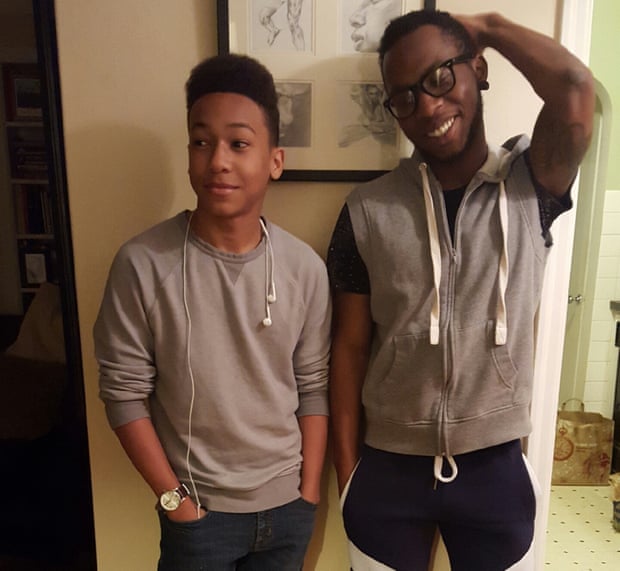

The construction of the new family continued when one of her adopted brothers, Izaiah, moved in with Dolezal when he was 16. She began calling herself his mother, although later she did adopt him as her son. That required more adaptions of the truth.

“Izaiah still calls me Mom. We figured out what to say. You were living with your dad in Chicago and now you’re living with your mom. Franklin’s your brother. Franklin looks like me, you look like your dad. It works,” she says. “We both knew people would assume that when we say I’m his mom, people are going to assume that’s biological. But at the same time, who cares?”

After Dolezal moved to Idaho, she embraced a new father figure. She met Albert Wilkerson, a former soldier and retired policeman, working at the Human Rights Education Institute where Dolezal was education director until 2010. “He kind of noticed that Franklin and I were alone family-wise and he was, you look like you need a dad and he needs a grandpa. I called him Dad,” she says.

In December, she posted a picture of herself, Izaiah and Wilkerson on her Facebook page with a caption: “Me, my oldest son Izaiah, and my dad.” It became a primary piece of evidence against her when the storm hit.

“I can see why people may have been confused. I did call him Dad because that described how we socialised. He would introduce himself as Rachel’s dad to my colleagues at work,” she says. “Nobody asked if that was my biological dad. Nobody asked, who are your biological parents?”

‘The backlash was meant to take me down. It did’

Dolezal’s world fell in when her biological parents went to the local paper. She said they went public to discredit her as a witness in a court case in which her younger sister accused her elder brother of sexual abuse. Her parents deny that was their motive, but the case was dismissed a few weeks later.

Dolezal had won a series of awards earlier in the year, including a Women in Business Leadership prize, and was on a professional high. She was asked by the black student union at Eastern Washington University to give the keynote speech at their graduation ceremony the day after the story ran. But by then she had been barred from the campus.

Dolezal, in 2009, standing in front of a mural she painted at the offices of the Human Rights Education Institute in Idaho, where she was education director at that time. Photograph: Nicholas K Geranios/AP

Her voice breaks as she relates her shock at the vehemence of the backlash. Social media lit up with derision and scorn. Columns by African-American intellectuals she respected accused her of being a fraud or, worse, a racist. Celebrities waded in. Dolezal was obliged to resign as president of Spokane NAACP, she lost her university job and was forced off Spokane’s police accountability commission, where she had been a strident voice against police racism.

“It was really hard. Within 24 hours everything was gone that I had worked for. I lost three-quarters of my friends. I had friends on Facebook sharing my photos with news sources. It got so out of hand, I had to close in really tight, have a small circle. Also to protect my kids. People were sending text messages: ‘Tell your mom to kill herself and do the world a favour.’” She wipes away tears with her hand.

Twitter hit out with a mocking meme, #AskRachel, posing questions it was supposed only African Americans could answer.

Rachel Dolezal walks out of interview about her race – video

On top of it all, a week later Dolezal discovered she was pregnant.

“A termination was out of the question. It was a surprise, but I’m not the first person to be surprised by a pregnancy. It’s another part of a new beginning. It’s given us all something to focus on that’s new, that isn’t tainted by all this other mess. All the funk that happened in June, we leave in June.”

But Dolezal can’t leave it in June. She is desperate to explain herself.

“I was accused of being a liar and a fraud and blackface from the beginning. If that narrative had been handed to me about somebody [else], hell yeah, I’d be upset. I’d be, what is this person doing? It doesn’t sound like somebody who is a good person,” she says. “It was meant to take me down. It did effectively do that, unfortunately.”

Amid the barrage of criticism, there were those who sought to explain Dolezal’s actions. Some drew parallels with those who have changed sexual identity, such as Caitlyn Jenner. Dolezal doesn’t see it – she rejects the idea that she is a black person in a white person’s body – and spurns the concept of “transracial”.

Franklin and Izaiah. Photograph: Courtesy of Rachel Dolezal

“I will admit that maybe it’s a useful word for some people in kind of stepping forward along the staircase of understanding identity. But I don’t like it because I don’t believe in race. To say ‘transracial’ further entrenches that idea,” she says. “I really feel we need to come up with better vocabulary.”

It’s an unexpected argument from a woman who has built an academic career around race and a life claiming to be black.

“Other people are operating on an autopilot that race is coded in your DNA, that there are different races of human beings and those races are called black, white, etc. As opposed to race is a fiction that was invented,” she says. “What I believe about race is that race is not real. It’s not a biological reality. It’s a hierarchical system that was created to leverage power and privilege between different groups of people.”

But race was real enough for her to call herself black.

“I think some people feel that if you question the reality of race you’re questioning racism, you’re saying racism isn’t real. Racism is real because people actually believe race is real. We’d have to really let go of the 500-year-old idea of race as a worldview in order to undo racism.”

But she does draw on the transgender experience to say that a person should not be defined only by what and who they were at birth or when they were younger. “Caitlyn Jenner has not been seen as a woman, and treated as a woman by other people, for her entire life. So what does that mean? What if somebody transitions as a teenager and their entire adult life we know them as a woman,” she says. “I hope we can reach some kind of term for the plurality of people and allow everybody to be exactly who they are on the spectrum of all these things. Religion, gender, race.”

Dolezal with students leading a parade for Martin Luther King Jr Day, 2014. Photograph: Courtesy of Rachel Dolezal

There is one person Dolezal identifies with, a South African woman called Sandra Laing, who was born black to a white family in the apartheid era. Laing was legally classified white but shunned by the white community and as a teenager eloped to Swaziland with her Zulu boyfriend.

“It’s a story that resonates personally, because of the themes of isolation, of being misunderstood, of being categorised different ways, by different people, put in different boxes, emancipating myself from boxes, being put in other boxes, and it just seems to be like this struggle of finding your place in the world and owning that place and being free to celebrate it,” she says.

‘Blackface is not pro-black. That was a pretty harsh accusation’

Dolezal has made a point of describing herself as black, not African American, a distinction derided by Vanity Fair, but one that black Africans in the US would recognise. She describes African American as a particular historical experience. To be black is broader, unbound by dates or borders.

“African American is a very short timeline if we’re talking about people who have ancestors who were here during child slavery, biologically connected to those ancestors. Which I know that I don’t have,” she says.

One of the things that has so infuriated some of her critics is their belief that she, unlike African Americans, has made a choice without experiencing the trials of what it is to grow up black in the US. She concedes this is true of her childhood, but claims that in identifying as black in recent years she drew that experience to herself.

“I have experienced being treated as a light-skinned black woman or biracial. Cops mark ‘black’ on my traffic tickets. When I applied for a job with a white male leaving, they said Rachel’s a coloured girl. He had a $70,000 salary. The job description was the same, but mine was $36,000. Even in romantic relationships, being exoticised by a white man or seen as the light-skinned black girl by a black man,” she says. “I was not only seen as a mixed chick or a light-skinned black woman, but I was seen as a radical black-power activist type: she teaches black studies at the college, she’s the president of the NAACP, she’s the head of the police accountability commission with all the police brutality issues, she is writing about racial issues.”

Other critics have constructed a picture of Dolezal rising in the morning, making herself up as black and consciously going out into the world as a fraud. That is not the perception of those who knew her best. Yet some of the strongest criticism has been over her use of spray tans and makeup to darken her skin. This is the area she is most hesitant to talk about.

“Do we ask women why they airbrush freckles on themselves or why they change their noses? We don’t ask if somebody’s boobs are real or not. I do my hair and my makeup and everything according to how I feel I’m beautiful. Sometimes I use a spray bronzer, sometimes I don’t,” she says. “Before this happened, nobody was asking me why are you lighter or darker on certain days of the week, depending on how much time I had to get myself together that day; if I had time to give myself a glow. And if I didn’t, I was out the door.”

But that does not answer the question of whether she was consciously trying to look black. It’s an issue she doesn’t address head-on. Similarly, with her hair, Dolezal says she has been putting in weaves and braids for 20 years and that plenty of women go for a different hairstyle.

“Is to copy to compliment or is it cultural appropriation? I think we need to talk about these things in the context of intention, in the context of what is authentic. Is it appropriation to change your genitals? Women have been getting perms – in white culture to get your hair curly, in black culture to get your hair straight – so a perm means altering your hair.”

Her changes in appearance looked to a lot of people like an attempt to give a physical form to her claim to be black. With that has come one of the accusations she finds more painful, of “blackface”.

“That was a pretty harsh accusation. I didn’t expect that at all because blackface, you don’t look like a light-skinned black woman, you look like a clown. It’s made to be a mockery. Blackface is not pro-black. Blackface is not working for racial justice. Blackface is not trying to undo white supremacy. I would never make a mockery of the very things I take the most seriously.”

Yet she gets where the criticism came from. “If I were to have heard all these accusations, or if I would have just read the script as it was without knowing me, as a black-studies professor, yes I would have thought the same. I think it’s just a matter of people being introduced to me through a certain lens that are saying those things,” she says.

That may be a fair criticism of the backlash from people who didn’t know her or appreciate that she worked hard within and for the black community. But if her friends and colleagues feel betrayed, it is because they too feel misled. Could she have done anything differently? She doesn’t give much ground.

“I planned to discuss my past and explain my life and decisions at a much later time, when my kids were all on their own as adults. But the opportunity to speak for myself was gone on 11 June. Maybe I could have told more people that I didn’t want to answer their questions, that my life is a personal matter, and the details of my identity are none of their business, instead of getting backed into corners by trying to answer their questions while protecting our family privacy,” she says.

But, in the end, people did not feel deceived because Dolezal answered their questions. Their sense of grievance lies with the fact that she hid the full truth behind a collection of distortions and by withholding information.

“I have thought long and hard about it and, given all the specifics of each encounter, I don’t think I would have changed things. I had a purpose before anyone had an opinion about me, and the opinions haven’t changed my life path,” she says.

For all the sense that Dolezal is unable to face up to her own part in creating the situation, it’s also difficult to believe she deserved what followed. She worked hard within the community she identified with, giving of herself and her time for others.

As she wipes away the tears, it’s hard not to think that she deserved a little of the humanity she has shown to others. Yet behind the pain is a determination not to be forced from the identity she has embraced.

“I really feel it hasn’t affected it at all because I wasn’t identifying as black in order to make people happy or make people upset or whatever. I wasn’t seeking fame. I was being me,” she says. “Of course, it’s affected me in really practical ways of not having a job. It’s really difficult to navigate public spaces. It’s been incredibly hard for my kids. There have been some real experiences, but one of them is not how I identify changing.”

Far from it. Her answer to her critics is to name her unborn son after Langston Hughes, the African American poet and leader of the Harlem Renaissance.

This article was amended on 14 December 2015, removing reference to a fake Twitter account.