By Patrick Kiger

How Stuff Works, May 8, 2017 —

In the United States, we put a lot of people — 2.3 million, at last count — behind bars for committing crimes. But we’re not as good at figuring out how to get offenders to go straight and succeed in jobs after their release. While recent data is scarce, a 2010 study by the Center for Economic and Policy Research estimated that there were as many as 6.1 million Americans of working age — more than 90 percent of them men — with a jail or prison record, and that they have so much difficulty getting hired it’s estimated that they account for nearly a full percentage point of the nationwide unemployment rate for males. This 2015 CNN story details the struggle of 41-year-old man to find work over an 18-month period after spending five years in prison for assault.

In order to help ex-offenders get a fresh start, 26 states and more than 150 cities and counties have joined the “Ban the Box” movement, prohibiting prospective employers from requiring job-seekers to check a box on employment applications to indicate a criminal history.

But even if they’re able to land job interviews, at some point ex-offenders still must explain that glaring gap in their resume created by incarceration. A new article by Michigan State University researchers in the Journal of Applied Psychology indicates that applicants who’ve been inmates have the best chance of being hired if they put it all out on the table, and admit remorse for their criminal past to potential employers.

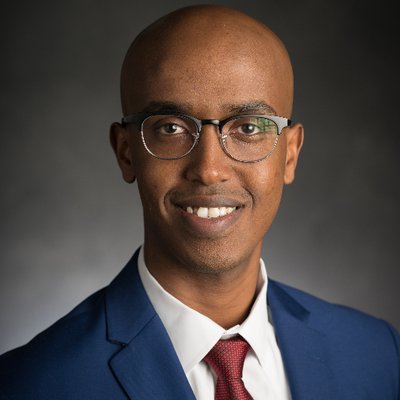

“The core issue that we were trying to address from a psychological perspective is how job applicants with a criminal record can best present information regarding their offense” to would-be employers, says Abdifatah Ali, a researcher in Michigan State University’s Department of Psychology. Photo by G.L. Kohuth

“Apologizing for your past criminal offense seems to be the most effective strategy in reducing concerns about your underlying trustworthiness as a person of integrity,” the article’s lead author, doctoral student Abdifatah Ali explained in an MSU press release.

The research involved three studies, in which more than 500 subjects evaluated job applications or watched a video of job interviews showing applicants trying to explain their criminal backgrounds. In some instances, the applicant made an excuse, such as saying that they were convicted because they happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, while others cited a justification for the crime, such as their need to help a family member. A third group admitted their wrongdoing and the harm that it caused, apologized for it and promised that it would never happen again.

The researchers found that apologizing was the most successful strategy for persuading subjects that a job candidate felt remorse and wasn’t likely to exhibit problematic behavior in the workplace. Justification also made a positive impression, the study found, but that is wasn’t as persuasive.

Applicants who made excuses definitely hurt their chances of being hired, the researchers found, because the evaluators still felt threatened by their history of criminal acts.