By Josie Glausiusz

Nature, January 29, 2019 —

Scientists with first-hand experience of rejection offer their advice.

Sibrina Collins felt humiliated when she learnt that her application for tenure had been denied. “That was an extremely painful experience,” she recalls. “You start to question your own intellect — ‘Is it me?’ I was really, really down about it.”

The inorganic chemist says that she had received positive two-year performance reviews at the College of Wooster in Ohio, and was shocked by the tenure rejection in her sixth year. But a group of friends whom Collins calls her “personal board of directors” helped to cushion the pain when it happened in March 2014. They told her to “look for the positive” in her tenure review.

And she found some. “There was a lot of good stuff in there,” she says. “The area where I was seeing some really nice results was in my scholarship.” As an African American, she had derived “peace and joy” from publishing many articles on the important contributions to science of women of colour.

Dr. Sibrina Collins, Executive Director, Marburger STEM Center

“My scholarship focuses on STEM [science, technology, engineering and maths] education, and on diversity, pedagogy and engaging students,” Collins explains. “So I realized that my next role had to allow me to focus on education and diversity in STEM. I didn’t see being denied tenure as a blessing, but having that door closed put me on a path to doing something I really enjoy.”

Collins is a rare example of a scientist willing to speak on the record to Nature about her tenure denial. Over four months, just seven scientists agreed to speak to Nature about their experiences; of these, two requested anonymity for themselves and for the institutions that denied them tenure. (“This took place 30 years ago and it still brings up hugely negative feelings,” one anonymous interviewee wrote.) Many declined to be interviewed, citing litigation, non-disclosure agreements, stigma and ongoing trauma. Others ignored e-mailed interview requests.

Researchers who agreed to speak on the record say that it is crucial that scientists maintain an active professional network, be as visible as possible through attending and speaking at conferences and within their institutions, and remain open to all career paths.

After Collins’s tenure denial, she was forced to admit to herself that she had not really wanted to be a faculty member. She won her current position in 2016 as executive director of the Marburger STEM Center at Lawrence Technological University in Southfield, Michigan, after a 16-month stint as director of education at the Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit, Michigan.

Nice work if you can get it

(Adapted from Getty)

Academic tenure is a central tenet of scholarly recruitment in North American universities, offering a job for life for those who can secure it. But it is becoming increasingly scarce in the United States and elsewhere.

Almost three-quarters of all US faculty positions are off the tenure track, according to a 2018 analysis of data by the American Association of University Professors in Washington DC. The United Kingdom abolished the tenure system in 1988 and replaced it with permanent or indefinite contracts. Other countries offer a mix of models that might or might not include tenure.

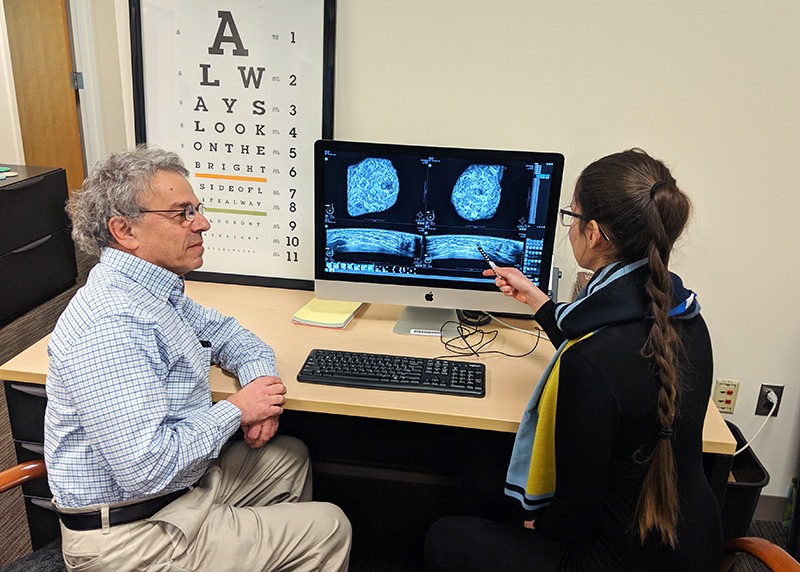

Given the scarcity of tenure-track jobs, rejection can be a calamitous blow to the psyche. Jeremy Wolfe describes his tenure rejection as a “grief situation”. Wolfe, who is now an ophthalmological researcher at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, and the founder of the Visual Attention Lab at Brigham & Women’s Hospital in Boston, was denied tenure at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 1990. “I really, really thought that I was going to make my career at MIT,” he says. “All of that went away.”

Wolfe’s tenure rejection came a year after he received a student-nominated award for his undergraduate introductory course in psychology, and was highly lauded in the student-published MIT newspaper. But his best-known papers had not yet received the citations they would garner in time. In 1989, he had published an analysis of “guided search”, the mechanism by which humans find targets in a crowded field of vision. The paper has now been cited more than 2,000 times.

A perceived lack of research publications can be an enormous barrier to tenure at leading research universities, says theoretical physicist Sean Carroll at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) in Pasadena. “What major research universities care about is research. Nothing else,” he says. Carroll has blogged about his experience of being denied tenure in 2006 at the University of Chicago, Illinois, and in a 2011 post he included some slightly tongue-in-cheek advice for faculty members aiming at tenure: bring in grants, don’t dabble and don’t write a book — because while you are writing a book or dabbling in other pursuits, you are not conducting research.

Carroll says that he was saddened by the denial and that he never received an official, on-the-record reason for it, but he suspects that it involved his varied non-research interests. The most common off-the-record explanation he received was that a textbook he had published — Spacetime and Geometry: An Introduction to General Relativity (Pearson, 2003) — was a bad choice because it was not physics research, he says.

Ever the optimist: Harvard ophthalmologist Jeremy Wolfe with a visiting graduate student. (Chia-Chien Wu)

Before he was denied tenure, Carroll says, he had received informal offers from other universities but had declined them because he was happy where he was. He warns that any such indications of interest might evaporate if a tenure application is denied. “If other places are looking to steal you away and you don’t yet have tenure, then take those opportunities very, very seriously. Don’t brush them off,” he says. “If your place wants to keep you, they will make you a better offer.”

Wolfe’s departmental chair had advised him at his third- or fourth-year review to look for a job offer elsewhere. He now sees that recommendation as a way of telling him to seek external proof of his professional value. “I never did that,” Wolfe recalls. “I had what is in retrospect a charmingly naive notion that loyalty to the institution was a good thing.”

Carroll says that he understands why many wish to remain silent about their tenure denial. “It’s the worst thing that can happen to you as an academic,” he explains. He advises tenure-track faculty members who are uneasy about a forthcoming tenure decision to seek solid offers elsewhere before the axe falls.

Wolfe says that he flung himself into the job market until he found his post at Harvard, where he had to re-apply for tenure. After his tenure denial, Carroll sought help from professional contacts, and in 2006 he landed his non-tenured research post at Caltech, where he remains to this day, focusing on his own research, writing books, giving talks and hosting a podcast. “The best revenge is doing well,” he says. “Whenever you have a major life change, re-evaluate what you’re doing and try to do it better. To go somewhere else and be even a pretty good success is what’s going to make you feel good.”

Denied by discrimination

But for those who were denied tenure because of alleged sexism or racism, such advice might rankle. One scientist, who asked to remain anonymous, says that over a 20-year period before, during and after her time at a certain Ivy League university, her department hired about 20 tenure-track faculty members, including her; half were men, and half women. Nine of the men received tenure, she says, and none of the women did. At the time of her own denial of tenure, she says, she had two grants from the US National Institutes of Health and 11 published papers, one in a high-impact journal; she also had 20 letters of recommendation, including some from Nobel prizewinners. “I was just as good as other young faculty coming up for tenure; I just wasn’t as visible,” she says. “That’s the word they used, unofficially — ‘visible’, and what they meant was famous in my field, having stature, clout.”

The researcher adds that, because of her shyness, she didn’t attend many meetings in her discipline and was never invited to present as a speaker. “We often do ourselves a disservice by not speaking up and promoting our science,” she says, adding that junior researchers must attend meetings regularly. “You have to project that you’re passionate about your science, that you have great ideas, and that you’re generating beautiful data.” The tenure denial still vexes her despite her earning tenure at a prominent US midwestern university.

Female researchers who are part of an ethnic or other minority group might face a further prejudice: the erroneous assumption, as one anonymous interviewee wrote in an e-mail, that African American women, people with disabilities and members of other minority groups earn tenure and promotion more easily than do their white male (or non-disabled) counterparts.

A 2016 report by the Teachers Insurance and Annuity Association of America (TIAA) Institute, based in New York City, found that although US universities and colleges had increased the diversity of their faculties in the past two decades, most of those gains had been off the tenure track (see go.nature.com/2lha3ah). Under-represented minorities, including African American, Hispanic, American Indian and Alaskan Native individuals, comprised 10.2% of full-time tenured faculty positions in US universities in 2013, the TIAA report found. The proportion of faculty members who are black and were hired between 2007 and 2016 fell from 7% to 6.6%, according to additional federal data analysed by the Hechinger Report, an organization based in New York City that covers higher education (see go.nature.com/2cgrpmz).

Erika Jefferson, President Black Women in Science and Engineering (BWISE)

Erika Jefferson, the founder and president of Black Women in Science and Engineering in Houston, Texas, says that the climate is still hostile towards minorities in some US universities. “There are certainly some wonderful schools that are supportive of everyone regardless of race and gender,” she adds. She says that female African American faculty members can benefit when their department contains other African American women who can share their experience and offer support.

Moving on swiftly

Some universities have a formal process for helping those whose tenure was denied to navigate the next steps. Julie Sandell, senior associate provost at Boston University in Massachusetts, says that doing just that is part of her remit. She says that the university aims to help those in their ‘terminal year’ (almost all colleges offer an extra year of teaching and research, during which academics can search for another post) with an easier transition, offering a reduced teaching load, for example.

And tenure denial is not always the end of the road. Most universities have an appeal process, and the appeal sometimes succeeds. “If people have any inkling that they want to appeal, I tell them they should appeal,” says Sandell. “Otherwise they might have regrets later on.” Not everyone sees the point of appealing, however. Collins, for example, decided against it, reasoning that she could be denied again.

One person who did decide to appeal is Terry McGlynn, an ecologist at California State University, Dominguez Hills, who at the time of his tenure denial was employed by the University of San Diego in California. “I was very confident that the appeal would not result in a reversal,” McGlynn wrote in an e-mail. “Nonetheless, I feel that it was worthwhile for me, because it gave me the opportunity to document the long series of procedural violations during my tenure review, and to provide an airtight rebuttal to the unsubstantiated statements in my file.”

McGlynn, who studies the ecology of litter-dwelling ants in the tropics, advises those considering an appeal to follow the paper trail, if one exists. “I think it’s important to know the actual reason the denial happened,” he says. Asked to comment on McGlynn’s allegations, Pamela Gray Payton, assistant vice-president, media communications, at the University of San Diego, responded: “It is our university’s practice to respect the privacy of current and former employees and thus, I am unable to discuss or comment on personnel issues.” Other universities approached for comment responded by saying that they could not comment on individual cases or specific employment situations. Sandell, meanwhile, advises researchers who are looking for a new position to identify what they most enjoyed about their work and consider what they might do next, rather than focus on their feelings of hurt and anger. Leaving academic research, as Collins did, is entirely viable, she adds.

Johannes Urpelainen found another path after he was denied tenure by Columbia University in New York City in May 2016. In July 2017, he was named founding director of the Initiative for Sustainable Energy Policy at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland. “Deal with it,” he says. “Get closure and move on. I think that’s a better way to live than holding a grudge.”

Dr. Johannes Urpelainen, Director, Initiative for Sustainable Energy Policy at Johns Hopkins University

Urpelainen says that his openness about his unexpected tenure denial — along with a solid professional network — helped him to find a new position despite his disappointment and fear. “I just let everyone know about it right away,” he says, adding that several opportunities came his way within two weeks of his denial. Urpelainen says that his new policy and research role, which is funded by a private endowment, suits him. “It worked out great for me,” Urpelainen says.

Ultimately, researchers say, a denial of tenure is not the end of the world. “You can be denied tenure and still have a very successful career,” Collins says. “I am truly thankful that some things that I once wanted did not work out for me, because I wouldn’t be here doing the work that I’m doing now if that decision had not happened.”

Nature 565, 525-527 (2019)