By Virginia Gewin

Ensia, May 15, 2018 —

Eddie Love was the lone African American in a cohort of 90 wildlife management students at Auburn University and one of the three people of color at his U.S. Forest Service internship in the western Great Plains region of the U.S. Still, he was surprised by the lack of diversity in the marine non-governmental organization community when he accepted a Roger Arliner Young (RAY) Marine Conservation Diversity Fellowship, part of a program designed to attract people of color to work on ocean issues.

Concerned that colleagues might not appreciate his background, culture or upbringing, he was pleasantly surprised that co-workers at two of the conservation non-profits behind the fellowship, Ocean Conservancy and Rare, welcomed him with open arms. They were more eager to address race and other inequities than he had anticipated. Following the fellowship, Love accepted a job to work on initiatives aiming at protecting marine mammals as well as efforts to increase diversity, equity and inclusion at the Ocean Foundation. He says he surprised himself by ending up in the marine field. “It never would have crossed my mind,” he says.

Ocean Foundation program associate Eddie Love is one of relatively few people of color who staff U.S. environmental organizations. COURTESY OF MARJA DIAZ / OCEAN CONSERVANCY

And that’s the problem: There are still relatively few connections between communities of color and the environmental sector. The ongoing lack of ethnic diversity on environmental organization boards and staff suggests that, overall, talk of increasing diversity has not turned into widespread action. There are signs, however, that some organizations are taking fundamental steps to seek out people with valuable, yet underrepresented perspectives and skills — and ensure a welcoming environment once they arrive.

Serious Disconnect

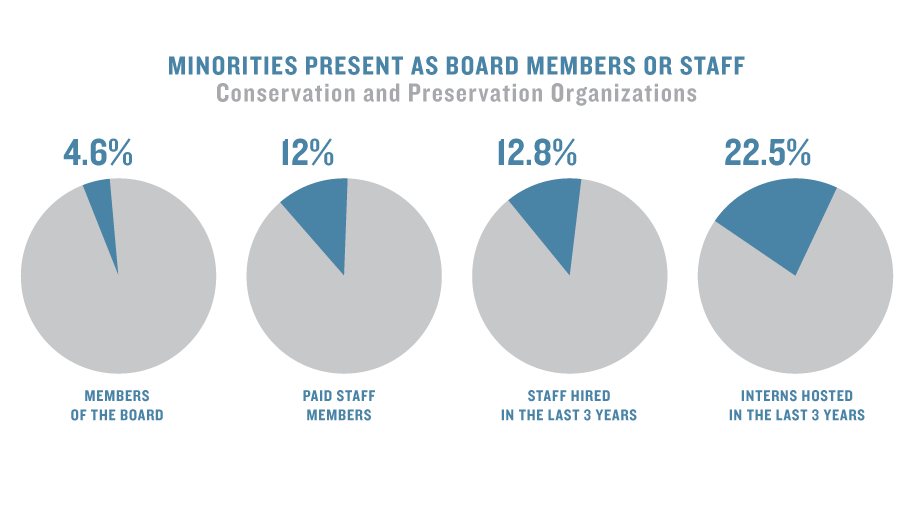

The lack of diversity in U.S. environmental non-profit organizations has been well chronicled in recent years. A 2014 study of 191 U.S. conservation and preservation organizations, 74 government environmental agencies and 28 environmental grant-making foundations found that ethnic minorities do not exceed 16 percent of board members and or staff of environmental organizations. In January 2018, study author Dorceta Taylor, director of diversity, equity and inclusion at University of Michigan’s School for Environment and Sustainability, released another report of 2,057 U.S. environmental nonprofit organizations, analyzing voluntary diversity data between 2014 and 2016. She found that 3.9 percent of organizations reveal their data on racial diversity; on average, 80 percent of their board members and 85 percent of their staff were white.

A number of organizations are diversifying their ranks in the wake of the reports. Asian American Rhea Suh became president of the Natural Resources Defense Council in 2014. Also in 2014, the Environmental Defense Fund created a 64-page diversity strategy. In 2015, Audubon created a statement outlining the organization’s diversity goals, and last year hired pioneering environmental justice lawyer Deeohn Ferris as vice president for equity, diversity and inclusion

Other environmental funding organizations and non-profits, however, are less forthcoming. The Pew Charitable Trusts and Conservation International, for example, do not share their diversity data and did not respond to repeated interview requests for this story. [Editor’s note: After publication, Conservation International contacted Ensia to explain that interview requests were misrouted. A representative told Ensia that 35 percent of Conservation International’s U.S. staff members — including CEO M. Sanjayan — are minorities, and the organization is a partner in EcologyPlus, an effort to connect diverse college students and early-career scientists with ecology careers.]

“It’s a good news, bad news situation,” says Taylor. “There is greater recognition that there’s a problem, but we are nowhere near where we should be in terms of hiring people of color.”

“There is a serious disconnect between the changing demographics in our country and the lack of diverse leadership and staffing at organizations that protect our health and the environment.” – Mustafa Ali

Mustafa Ali, senior vice president of climate, environmental justice and community revitalization with the Hip Hop Caucus, a national non-profit that encourages civic engagement, agrees.

“Numbers don’t lie,” he says. “There is a serious disconnect between the changing demographics in our country and the lack of diverse leadership and staffing at organizations that protect our health and the environment.”

Systemic Change

Diversifying environmental non-profits takes time, patience and, most importantly, thoughtful, sustained action. In 2017, The Wilderness Society reported that people of color held 4 percent of its senior staff positions, 14 percent of all staff positions, and 10 percent of its board positions. Society president Jamie Williams realized the organization needed to make systemic changes to the board, staffing and partnership efforts to better achieve its mission of protecting public lands.

The first step, he says, was to be more representative of the communities they aim to serve — and that required outreach. Throughout the organization — from adjusting its mission to include the needs of underserved communities to addressing unconscious bias in hiring practices — the society is working to embed equity and inclusivity into everything it does, he says. “We learned we need to be intentional about change, not just well-intended,” says Williams.

Broadening the organization’s focus beyond protecting the biggest, wildest places, the Wilderness Society launched an Urban to Wild initiative to protect outdoor recreational areas close to and within cities and increase public transportation from cities to these areas — making it easier for city dwellers, including people of color, to access the outdoors. In addition, the society is working to increase the racial and ethnic diversity of the staff, in part by establishing paid internships. One-third of the 15 people hired in the past year have been people of color.

“We know we still have a lot of work to do,” says Williams, “but [these efforts] will make us a much stronger, dynamic organization over the long run.”

Queta González helps organizations develop strategies to increase equity, diversity and inclusion in her role as director of Center for Diversity & the Environment in Portland, Oregon. She says organizations that successfully attract and retain diverse staff and develop cross-cultural relationships are clear about their goals, transparent, accept feedback, and are authentic.

“If you don’t do it authentically,” says González, “just don’t do it.”

Inauthentic gestures — for example, promoting diverse faces on an organization’s website without concomitant shifts in outreach or recruitment — are a common misstep. Another is focusing too much on increasing the number of people of color hired, instead of investigating why the numbers are so low and addressing the root causes, says Charles “Chas” Lopez, vice president for diversity and inclusion at Earthjustice, a San Francisco–based environmental law nonprofit.

Mary Scoonover, executive vice president of the California-based conservation non-profit Resources Legacy Fund, says her organization has, since inception, focused on broadening, ethnically and economically, the groups and leaders who advocate for conservation. But they decided 10 years ago they needed to do more to diversify their board and staff.

2014 study showed that racial diversity in U.S. conservation and preservation organizations tends to be lowest on boards and highest among relatively new employees and interns. SOURCE: TAYLOR, D.E. THE STATE OF DIVERSITY IN ENVIRONMENTAL ORGANIZATIONS; CHART BY SEAN QUINN

The organization found it challenging to recruit ethnically diverse, younger staff to suburban Sacramento, where the organization was originally based. So it made a big move — opening an office in Los Angeles and expanding their presence in San Francisco, in part, to help attract high-caliber candidates from diverse backgrounds.

The organization has also spent time reaching out to local schools and colleges, championing conservation as a career choice. And it created a new category of entry-level managers to offer employees the experience necessary to become leaders of tomorrow. Five years ago, the group’s seven-member board had no people of color. Now, the 11-member board has three people of color. The percent of people of color on staff has gone up from 9 percent to 26 percent since 2015.

“We’re slowly increasing our diversity,” Scoonover says, but admits, “we have more progress to make.” To continue to build a broader, more diverse coalition, the Resources Legacy Fund is looking for synergies between its own mission and a community’s priorities — for example, connecting its concern about air quality with diverse farmworkers’ concern about pesticide drift.

Building Relationships

Despite the increasing number of fellowship, internship and training opportunities to provide people of color with pathways to gain skills and experience in environmental fields, organizations continue to lament a lack of diverse applicants.

Taylor says that type of rhetoric is used to absolve organizations of a responsibility to search out or nurture talent. She is involved in two fellowships for college students of color to gain experience in university research labs and non-profit organizations — yet her program staff receives only a modest number of job advertisements from environmental organizations.

“Environmental jobs are advertised and accepted through established networks,” says Taylor, adding “if you are not connected, you won’t hear about or get those jobs.”

A New Horizons in Conservation Conference held in April 2018 brought together students and alumni of University of Michigan diversity programs. Many environmental groups participated as panelists or recruiters. Photo courtesy of Dave Brenner, University of Michigan

To help build those connections, Taylor organized a New Horizons in Conservation Conference in Washington, D.C., in April 2018. Over 220 participants — mostly students of color — attended with resumes in hand to mingle with representatives of non-profits. This September, the sixth annual HBCU Climate Conference, which brings together Historically Black College and Universities staff, faculty and students, will take place in New Orleans and expects 400 attendees. Over 30 percent of past attendees have gone on to pursue careers in environmental fields, says conference organizer Beverly Wright.

“I want to dispel the myth that there are not diverse young people out there interested in this work,” says Angelou Ezeilo, CEO and founder of Greening Youth Foundation in Atlanta, Georgia. Her organization has trained over 5,000 underserved, underrepresented young adults, ages 16–25, in environmental stewardship — ranging from conservation to urban agriculture to landscape management.

Ezeilo estimates only 15 to 17 percent of her trainees have secured long-term employment in environmental organizations. But she also notes that she measures success not by employment, but by the number of people she exposes to environmental fields — trainees who now see things through a lens of sustainability even if they wind up in other professions. Still, “there have to be employers ready to hire them,” she says.

Changing Culture

Changing an organization’s culture takes time and deliberate action. When you commit to do this, you have to go all in, says Center for Diversity & the Environment’s González. “I see a lot of organizations put a toe in the water and try to recruit for diversity but do nothing to create an inclusive environment,” she says. If new hires walk into a space where they don’t feel welcome, the situation is set up for failure, she says.

Photo courtesy of Joy Asico/Ocean Conservancy

The Ocean Foundation’s Love agrees that retaining diverse staff will be the key to success. “How do groups plan to keep diverse staff, and create an environment that seeks to understand diverse backgrounds and communicate effectively?” he asks.

To that end, González says one of the most important thing an organization can do is center its actions around the answer to one question: Why does diversity matter to us?

“Organizations need to see diversity as a great opportunity,” she says. “If it’s drudgery or scary, it will fail.”

Ali offers one answer: “If we truly want to win on climate and the environment, that means all voices must help drive the process.”