By: Stephen Bartos, Professor of Economics, University of Canberra

This week the Albanese government produced a detailed breakdown of the A$3 billion it plans to save over four years by cutting the use of outsourced labour and consultants.

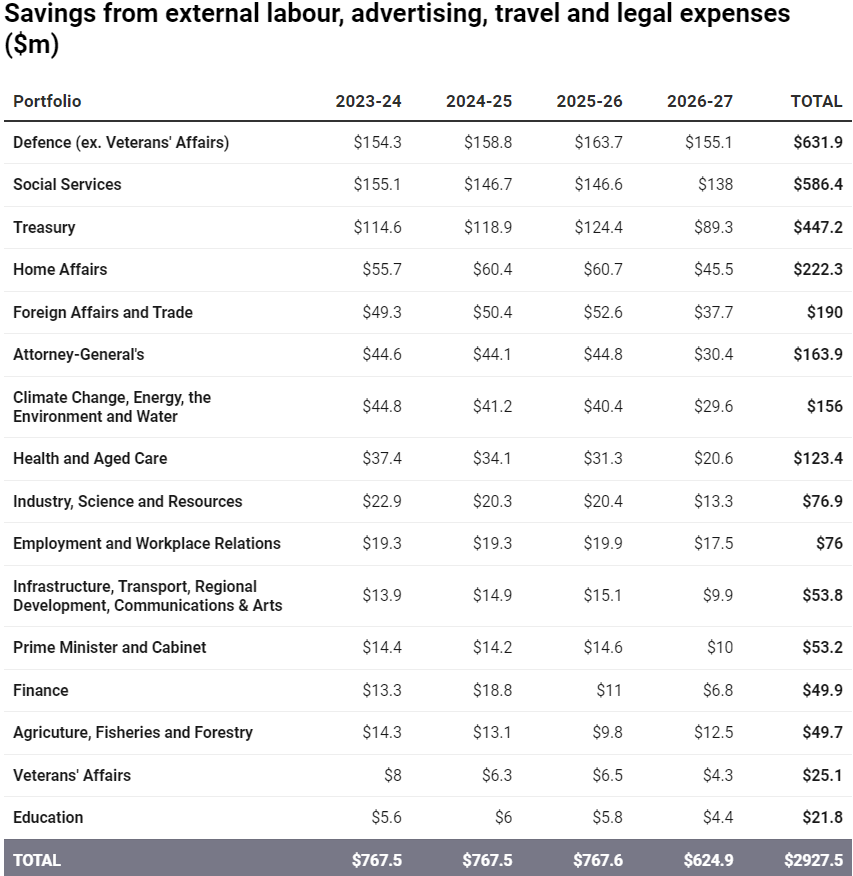

The savings, which begin this financial year, take about $600 million each from the departments of defence and social service, followed by about $450 million from the treasury, most of it to be reportedly from the tax office.

They cover what the government describes as “savings from external labour, advertising, travel and legal expenses”. They are in line with the Labor’s election promise to cut its consulting and contractor bill by $3 billion over four years, except that the starting year is 2023-24 instead of the expected 2022-23.

Given that Labor says it’s already cut $500 million in its first year in office, they are set to take the five-year total to $3.5 billion.

But the cuts won’t come easily, a point Finance Minister Katy Gallagher conceded in an interview with the Australian Financial Review, saying it had

become very clear just how entrenched the use of consultancies and external labour became in the public service under the former Coalition government.

There’s nothing wrong with moderate use of consultants and contract labour. It’s been done by both sides of politics for decades.

More than 30 years ago, the then Labor government’s commercial support program outsourced defence functions, including cooking, cleaning, maintenance and guarding, to deliver services at a much lower cost than the military.

Outsourcing weakens accountability

The concern is the extent to which core public service functions – policy advice to ministers and delivery of welfare programs – have also been outsourced.

The public service has (or ought to have) a corporate memory of what works and what does not. Consultants hired on a one-off basis need not.

It is true that the public service does not always live up to its legislated standards, as has been found to have been the case with Robodebt. But it can be held accountable when it fails.

Accountability mechanisms for private consultants and contractors are weak by comparison, with failings often obscured by a veil of “commercial in confidence”.

Why consultants seemed so attractive

In The Conversation in June, Richard Mulgan expertly analysed the findings of the audit of employment Labor commissioned shortly after taking office.

He listed three reasons why public servants like using consultants:

- they allow governments to bury advice they don’t like

- they help persuade ministers who distrust the public service. This is especially important with Coalition ministers.

- they maintain a revolving door for public servants to leave their job, collect their super and continue working on the same issues.

There is a fourth, more venal, reason – the millions of dollars consultants spend each year entertaining public servants.

One such prized invitation is to a private marquee at the annual Prime Minister’s XI cricket match at Manuka in Canberra.

There are hundreds of other dinners, lunches, private boxes at sporting events, theatre and concert tickets with which consulting firms seek to influence public service decision-makers.

The firms wouldn’t be spending that money if it didn’t win them business.

These constitute formidable obstacles. But there are three ways they could be overcome.

1. End the free lunches

One measure would be for departments to ban their staff from accepting gifts and hospitality from consulting firms.

If that is regarded as too much of an imposition, departments could publish all such gifts on their websites, disclosing the names of recipients and the value of what was received.

That would at least make what happens more open.

2. Stop insider hiring

Another would be to prohibit public servants from obtaining employment in a consulting firm with which their former department does business.

This could be done either through “non-compete” clauses (common in the private sector) or through departments excluding firms that employ former departmental staff from tenders. A reasonable time limit – for example between three and five years – could apply.

3. Tender internally first

Commonwealth procurement rules could be amended to require departments, before calling for tenders from outside the public service, to advertise internally for public servants to do the work.

The work would then only be sent out to a consultant if no public servant could be found to do it. Who knows, that might even encourage some former public servants to return from consulting back to their old jobs.

Getting senior public servants to want to use their own staff instead of consultants might be an unintended benefit of the PwC scandal.

Until May this year – when PwC confirmed one of its partners had shared confidential government information obtained while serving on a government advisory board – many public servants considered using consultants low-risk.

It has become clear it involves a much higher risk than hiring a public servant.