By Colin Vanderburg

Los Angeles Review of Books, November 24, 2016 —

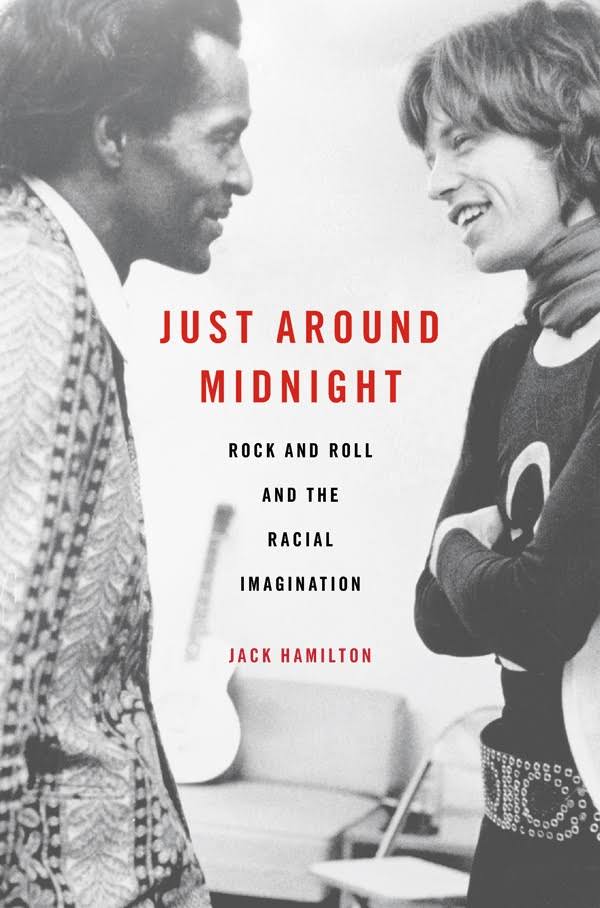

THAT BOTH BLACK AND WHITE musicians have a place in the history of rock and roll is a truism. But, as the cultural historian Jack Hamilton shows in his new book Just Around Midnight: Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination, almost nothing else about the music’s racial makeup is simple or settled. From Little Richard and Chuck Berry to the Dominoes, Ike Turner, and Howlin’ Wolf, rock and roll’s founding figures were African American, yet “rock” as we know and hear it now is coded white. In Hamilton’s telling, rock’s long evolution from a raucous offshoot of black party music to a lavishly produced, aesthetically ambitious, and securely white art form “is a story of the forced marriage of musical and racial ideology.”

Critics and fans have found three ways to account for this “whitening,” Hamilton argues, each serving different agendas and audiences.

The first draws a direct line from rock and roll back to blackface minstrelsy, implicating the music in a long legacy of “white-on-black cultural theft,” and charging that Elvis, the Beatles, and the rest simply “stole” their sound from Chuck Berry and his contemporaries.

The second contends that “black music effectively self-segregated” in the 1960s, in line with the splintering of the civil rights movement along racial lines and new, radical expressions of black power and pride, forging a new path into new musical genres and leaving white rock musicians to their own devices.

Finally, there is “the third, and by far most common, way that the ‘whitening’ of rock and roll music has been discussed,” in which the African-American influence on white rock is either simply effaced or is turned into one of many sociological conditions for the development of the genre. Hamilton, quoting the critic Fred Moten, finds this an instance of “white avant-gardism whose seriousness requires either an active forgetting of black performances or a relegation of them to mere source material,” in which artists like Richard and Berry figure as primitive progenitors, valuable only for enabling what came later: the familiar lineage of Elvis, the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, and all the other white stars that fill the classic rock pantheon. Advocates of such a history could be compared to critics who can satisfy their curiosity about the sources of Picasso’s early sculptures by vaguely labeling them “African masks.”

For Hamilton, none of these narratives will do. The first, which emphasizes theft, is commendable in its stance against cultural appropriation, but flattens rock history into a racial morality tale. The second “self-segregation” story ignores the crossover and collaboration that characterized pop, rock, and soul throughout the ’60s and beyond. The third, which treats musical influence as an almost occult force, is at once the most mistaken and the most ingrained, the hardest for the critics and listeners to shake.

The idea of black music as raw material is at the core of what Hamilton calls “rock’s ideology of authenticity,” in which the music was always destined to develop into a more sophisticated, and necessarily “white,” art.

Such ideas, Hamilton claims, must be taken apart before we are able, in his words, “to hear this music differently, more complexly, and more clearly: in other words, to hear it better.”

Just Around Midnight Rock and Roll and the Racial Imagination, By Jack Hamilton, Harvard University Press

Hamilton locates the origins of these ideas more or less where we might expect: in the racial imagination of the white rock critics of the 1960s, architects of what is today sometimes called “rockism”: a critical aesthetic that takes the (white) rock music of the 1960s and ’70s as the mean from which all other pop forms deviate. Though some rock critics certainly ignored black artists outright, more often rockist writing venerated black music, provided it conformed to an expected set of cultural signifiers, preferably those of an ostensibly primitive past.

In some of his sharpest passages, Hamilton shows how much rockism’s whiteness depended on these confining ideas of blackness.

In 1968, as black artists enjoyed unprecedented chart success, the critic Mike Gershman dismissed “denatured Negroes” who had “learned only too well … the value of getting Top 40 airplay,” in the process abandoning “the Negro blues, the most honest and meaningful contribution of black people.” Many even found fault with Motown — maybe the most unanimously beloved music the United States has produced — for what they saw as its commercialized, diluted blackness: Hamilton notes that historian Peter Guralnick “excluded [the label] from his otherwise excellent history of 1960s R&B […] on the grounds that it is not ‘soul music’” because it appealed, in Guralnick’s words, to a “far more to a pop, white, and industry-slanted kind of audience.” Even sympathetic white scholars remained blinkered by the belief that “real” black music had to be rough, raw, natural, pure.

While such attitudes about black artistic expression have circulated for centuries, Hamilton traces their outsized influence in rock criticism to the midcentury folk revival. In the pages of the Little Sandy Review, a proto-fanzine co-edited in the early 1960s by Paul Nelson (then an undergraduate at the University of Minnesota and later a prominent critic for Rolling Stone), the highest praise a black musician could earn was the kind bestowed on a solo-acoustic album by John Lee Hooker, commended “for returning to his ‘primitive and harsh’ style,” a truer sound than “his recent, ‘more sophisticated’ recordings.” Hamilton cites another Little Sandy contributor who celebrated songster and penitentiary inmate Robert Pete Williams as “a singer who has developed to a fabulous level of artistry in an all-Negro environment completely free of any reason or desire to ‘refine’ for a sophisticated folkum market” — as if Williams’s musical blackness was a precious substance that could be kept isolated and unsullied. (Such tributes to what Hamilton cleverly terms “authenticity-through-incarceration” might give pause to some of Gucci Mane’s more ardent white fans.)

The dehumanizing noble savagery behind such passages is only barely disguised. While breathlessly praised for their “artistry,” black musicians are never allowed to make “sophisticated” or “refined” art. For these writers the very notion appeared laughably incompatible with black music. The result, Hamilton writes, was “a near-incoherent double standard”: “black artists [were] derided as ‘Toms’ for aspiring to make money, then castigated for conforming to expectations of musical blackness on the part of white listeners” — a group, of course, to which all these critics belonged.

In practice, the rockist preoccupation with purity confined black music to the realm of communal experience and raw instinct, while individual genius and high-minded experimentation were reserved for white artists.

In one of the book’s strongest sections, Hamilton compares the disparate ways that artistic leaps taken by Bob Dylan and Sam Cooke were received. The image of Dylan “going electric” in 1965 at the Newport Folk Festival and storming the Top 40 with “Like a Rolling Stone,” is by now a mythic cliché of white rock-star defiance and artistic autonomy. Though Dylan’s folkie fans were appalled at the time, the story is now remembered as one of a restless genius’s search for a new sound. Cooke, by contrast, has never been studied, or heard, with the same seriousness. Though it has been quoted and adapted by countless musicians and has served as an anthem of collective black struggle, his 1964 masterwork “A Change Is Gonna Come” has received only a fraction of the critical attention that even Dylan’s minor lyrics have, and most stories of the song’s genesis emphasize that Cooke was moved to write it after hearing Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind.”

Meanwhile, the album Sam Cooke at the Copa, recorded that same year, in which Cooke glides through a nightclub set of standards and showtunes, has been dismissed by white canon-builders as so much glitzy pandering to a clueless, “soul”-less white audience, while his rougher, looser performance for a black audience at Miami’s Harlem Square Club, recorded a few months earlier, made Rolling Stone’s list of the “500 Greatest Albums.” Hamilton points out that the only criterion by which Cooke’s Copa performance, which is as smooth and suave as the Harlem Square set is wild, can be called “inauthentic,” is the same standard that demands that all black art be raw and un-self-conscious, while expecting white music to be searching and cerebral. Cooke commanded both stages with equal talent and commitment; indeed, the sheer distance between the two performances is the mark of an artistic range at least as impressive as Dylan’s more celebrated transition from protest singer to rock star.

Rockist assumptions about race and authenticity could be used to censure white artists as well. In one fascinating chapter, Hamilton tracks the trajectory of what could be called the “soul question,” which in the ’60s became a minor obsession in the American music press, a collective complex of racial anxiety. Did Janis Joplin have soul? Could she? Did soul require blackness, or a certain kind of historical suffering? Unsurprisingly, the debate split along racial lines. For black critics, soul could be equal parts struggle and swagger, but was black in essence: “Soul is a poor-paying job where ‘white’ is the only color respected for upgrading and job-promotion,” wrote Thaddeus T. Stokes in a 1968 issue of the Daily World, Atlanta’s major black newspaper. “Soul is sass, man,” declared Claude Brown in Esquire that same year. “Soul is arrogance […] bein’ true to yourself […] [that] expression that goes into practically every Negro endeavor.”

White critics disagreed. In The New York Times, Albert Goldman was one of a chorus of white writers who countered that soul was a spirit that transcended race, a gift from black to white America: “black and white are attaining within the hot embrace of Soul music a harmony never dreamed of […] Adopting […] the firmly set, powerfully expressive mask of the black man […] [white musicians] are released in to a […] freedom denied them by their own inherited culture.” Goldman’s article, entitled “Why Do Whites Sing Black?” elicited “a flurry of letters,” including a rejoinder from a group of black Smith College students that could still stand today:

“The thing you white people always get mixed up over is that black music cannot be dissected into meters and patterns. For every black song there are a hundred ways a black person can sing and play it.”

The terms and the music have changed but many of the questions, tropes, and insecurities remain. To a unique degree, American pop music remains segregated by audience and genre, with categories like “pop” and “urban” still denoting, respectively, white and black listeners and musicians. The current Billboard Hot R&B/Hip Hop singles chart was known as the “race records” list in the 1940s, and for most of the 1980s was even known as “Hot Black Singles.” (Imagine if The New York Times tallied separate best seller lists for black and white authors and readers.) If anything, our anxieties over authenticity and appropriation have only deepened since the era Hamilton studies. If the ’60s debates over “soul” appear silly today, it doesn’t mean we’re any closer to a racially liberated pop music: in some cities rap lyrics have been effectively criminalized, and young black men arrested and charged based on violent boasts in their verses.

Ironically, it may be music critics, in many ways the ideological culprits in Hamilton’s story, who have done the most — after the artists themselves, of course — to unsettle the racial categories that have stunted our understanding of rock history. Outlets from The New Yorker to The Fader to MTV News now regularly feature music writing by young critics of color who approach pop, rap, and rock with a far sharper, subtler, and, above all, varied racial awareness than the white writers Hamilton cites. Meanwhile, much of the most inept writing on race and music continues to come from white male critics. Even articulate and aware writers traffic in old, reified notions of “soul” and “funk,” the immaterial essences by which they define, and otherize, black music.

And while the pitiful spectacle of white college misfits styling themselves as arbiters of the authenticity of African-American expression is no longer the only game in town, these attitudes are far from extinct, particularly when it comes to music history. Early blues musicians and R&B singers are still routinely tagged and marketed as key “influences” who “gave us” Bob Dylan or Led Zeppelin or the Rolling Stones, as if without these white inheritors to fulfill some musical prophecy, their work would be of little interest.

Part of the problem is the continued centrality of the ’60s — the decade when the mantle of rock and roll passed from black to white musicians — to our accounts of pop history (in part a side effect of ’60s music’s ongoing status as a marketing cash cow for boomer nostalgia). Unfortunately, Just Around Midnight’s narrow chronological focus, while justifiable in an academic work of cultural history, reinforces this paradigm somewhat. Certainly the archive is rich enough: the ’60s were an explosive decade in pop music as in politics, marked equally by miscegenation and collaboration and by repression and rebellion. It would be foolish to argue that the decade wasn’t important, even revolutionary. Nevertheless, race in American pop is an unending story, and Hamilton could have carried his themes through the years of Prince and Michael Jackson, through the Backstreet Boys and Beyoncé to the present, genre-transcending sounds of Frank Ocean’s Blonde and Solange’s A Seat at the Table. The phenomenon of someone like Teena Marie, a white singer who supposedly sounded so “black” that fans of both races were shocked when they saw her on television, could benefit from Hamilton’s careful deconstruction. Indeed, given the inherent visuality of racial identity — the way images shape, distort, and encode our tastes and prejudices — Hamilton’s reliance on a narrow range of written sources seems needlessly limiting.

Nevertheless, if Hamilton sometimes struggles to balance his book’s critical ambition with its historical specificity, he contributes a new and valuable piece to a larger and still contentious project: the struggle against the essentialization of racial and ethnic identity. Hamilton, like me, is white, which makes taking this position somewhat fraught — who are we, who have stolen and suppressed so much, to warn artists of color against claiming any art as inalienably theirs? But to fully free rock from the taint of rockism and really hear this often overfamiliar music once again, taking an anti-essentialist stance is finally unavoidable. Tagging any art or a style as vitally and irreducibly belonging to one people can be liberating, even necessary, for the communities who create it, but ultimately it becomes just one more way to contain, control, and commodify something that should be, in every sense, free.

¤

Colin Vanderburg is a Brooklyn-based writer and an assistant editor at Monthly Review.