By Sarah Lewis, Assistant Professor Harvard University

The New York Times, The Lens, April 25, 2019.

This week, Harvard University’s Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study is hosting Vision & Justice, a two-day conference on the role of the arts in relation to citizenship, race and justice. Organized by Sarah Lewis, a Harvard professor, participants include Ava DuVernay, Henry Louis Gates Jr., Wynton Marsalis and Carrie Mae Weems. Aperture Magazine has issued a free publication this year, titled “Vision & Justice: A Civic Curriculum” and edited by Ms. Lewis, from which we republish her essay on photography and racial bias.

— James Estrin

Can a photographic lens condition racial behavior? I wondered about this as I was preparing to speak about images and justice on a university campus.

“We have a problem. Your jacket is lighter than your face,” the technician said from the back of the one-thousand-person amphitheater-style auditorium. “That’s going to be a problem for lighting.” She was handling the video recording and lighting for the event.

It was an odd comment that reverberated through the auditorium, a statement of the obvious that sounded like an accusation of wrongdoing. Another technician standing next to me stopped adjusting my microphone and jolted in place. The phrase hung in the air, and I laughed to resolve the tension in the room then offered back just the facts:

“Well, everything is lighter than my face. I’m black.”

“Touché,” said the technician organizing the event. She walked toward the lighting booth. My smile dropped upon realizing that perhaps the technician was actually serious. I assessed my clothes — a light beige jacket and black pants worn many times before in similar settings.

As I walked to the greenroom, the executive running the event came over and apologized for what had just occurred, but to me, the exchange was a gift.

My work looks at how the right to be recognized justly in a democracy has been tied to the impact of images and representation in the public realm. It examines how the construction of public pictures limits and enlarges our notion of who counts in American society. It is the subject of my core curriculum class at Harvard University. It also happened to be the subject of my presentation that day.

‘Race changed sight in America.’

It is what my grandfather knew when he was expelled from a New York City public high school in 1926 for asking why their history textbooks did not reflect the multiracial world around him. The teacher had told him that African-Americans in particular had done nothing to merit inclusion. He didn’t accept that answer. His pride was so wounded after being expelled that he never went back to high school. Instead, he went on to become an artist, inserting images of African-Americans where he thought they should — and knew they did — exist. Two generations later, my courses focus on the very material he was expelled for asking about in class.

After the presentation was over, the technician walked toward me as I was leaving the auditorium. I had nearly forgotten that she was there. She apologized for what had transpired earlier and asked if one day she might sit in on my class.

What had happened in this exchange? It can be hard to technically light brown skin against light colors. Yet, instead of seeking a solution, the technician had decided that my body was somehow unsuitable for the stage.

Her comment reminded me of the unconscious bias that was built into photography. By categorizing light skin as the norm and other skin tones as needing special corrective care, photography has altered how we interact with each other without us realizing it.

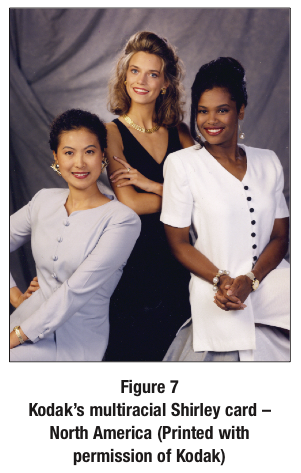

Photography is not just a system of calibrating light, but a technology of subjective decisions. Light skin became the chemical baseline for film technology, fulfilling the needs of its target dominant market. For example, developing color-film technology initially required what was called a Shirley card. When you sent off your film to get developed, lab technicians would use the image of a white woman with brown hair named Shirley as the measuring stick against which they calibrated the colors. Quality control meant ensuring that Shirley’s face looked good. It has translated into the color-balancing of digital technology. In the mid-1990s, Kodak created a multiracial Shirley Card with three women, one black, one white, and one Asian, and later included a Latina model, in an attempt intended to help camera operators calibrate skin tones. These were not adopted by everyone since they coincided with the rise of digital photography. The result was film emulsion technology that still carried over the social bias of earlier photographic conventions.

It took complaints from corporate furniture and chocolate manufacturers in the 1960s and 1970s for Kodak to start to fix color photography’s bias. Earl Kage, Kodak’s former manager of research and the head of Color Photo Studios, received complaints during this time from chocolate companies saying that they “weren’t getting the right brown tones on the chocolates” in the photographs. Furniture companies also were not getting enough variation between the different color woods in their advertisements. Concordia University professor Lorna Roth’s research shows that Kage had also received complaints before from parents about the quality of graduation photographs — the color contrast made it nearly impossible to capture a diverse group — but it was the chocolate and furniture companies that forced Kodak’s hand. Kage admitted, “It was never black flesh that was addressed as a serious problem at the time.”

Fuji became the film of choice for professional photographers shooting subjects with darker tones. The company developed color transparency film that was superior to Kodak for handling brown skin. Yet, for the average consumer, Kodak Gold Max became appealing. This new film was billed as being “able to photograph the details of a dark horse in lowlight,” a coded message for being able to photograph people of color. When I first learned about this history, I finally understood why my father went, almost obsessively, to the camera store down the street from our apartment in Manhattan in the 1980s to buy Kodak Gold Max film.

Digital photography has led to some advancements. There are now dual skin-tone color-balancing capabilities and also an image-stabilization feature — eliminating the natural shaking that occurs when we hold the camera by hand and reducing the need for a flash. Yet, this solution creates other problems. If the light source is artificial, digital technology will still struggle with darker skin. It is a merry-go round of problems leading to solutions leading to problems.

Researchers such as Joy Buolamwini of the MIT Media Lab have been advocating to correct the algorithmic bias that exists in digital imaging technology. You see it whenever dark skin is invisible to facial recognition software. The same technology that misrecognizes individuals is also used in services for loan decisions and job interview searches.

Yet, algorithmic bias is the end stage of a longstanding problem. Award-winning cinematographer Bradford Young, who has worked with pioneering director Ava DuVernay and others, has created new techniques for lighting subjects during the process of filming. Ava Berkofsky has offered her tricks for lighting the actors on the HBO series Insecure — including tricks with moisturizer (reflective is best since dark skin can absorb more light than fair skin). Postproduction corrections also offer answers that involve digitizing the film and then color correcting it. All told, rectifying this inherited bias requires a lot of work.

What is preventing us from correcting the inherited bias in camera and film technology? Is there not a fortune to gain by the technology giant who is first to market?

In the meantime, artists themselves are creating the technology for more just representation. We are hearing more about issues with race and technology as we consider the importance of inclusive representation with the success of films from “Black Panther” (2018) to “Crazy Rich Asians” (2018). Frederick Douglass knew it long ago: Being seen accurately by the camera was a key to representational justice. He became the most photographed American man in the 19th century as a way to create a corrective image about race and American life.

Yet, for many, the question is still: Why does inclusive representation matter so much? The answers come through viral examples such as the image of a young 2-year-old Parker Curry gazing up at Michelle Obama’s portrait by Amy Sherald at the National Portrait Gallery, her mouth dropped open, convinced that Mrs. Obama was a queen. Former White House photographer Pete Souza has captured an image of a young boy, just 5 years old, who wanted to know if his hair texture really did match that of the president. You can’t become what you can’t accurately see.

I often wonder what would have come of more time to talk with the technician. Her eyes were glassy as she said goodbye. Mine were, too, grateful for her vulnerability. The exchange was the result of decades of socialization that we often don’t acknowledge has occurred whenever we look through the lens.

Race changed sight in America. This is what my grandfather knew. This is what we experience. There is no need for our photographic technology to foster it.

Sarah Lewis is an assistant professor at Harvard University in the department of history of art and architecture and the department of African and African-American studies. She is an author, a curator and the guest editor of the “Vision & Justice” issue of Aperture (2016), which received the 2017 Infinity Award for Critical Writing and Research from the International Center of Photography. This week’s event grows out of her research and teaching in her course, Vision & Justice: The Art of Citizenship.