By Eda Yu

Vice, May 31, 2019.

The first time I felt ashamed of being Asian, I was six years old. It was my first day in the first grade at a new, predominantly white school, where I was surrounded by people who didn’t look like me. But as I was sitting on the swings alone, a young Chinese boy approached—the first fellow Asian I’d seen.

“Hi! Are you new here?” he asked.

His voice didn’t sound like mine, or those of any of the kids at the Chinese-English kindergarten I had attended until then. It sounded purely American.

“First day,” I said shyly, my accent thick and unforgiving.

He frowned at my response, then ran off, beckoned by his group of white friends. I was left confused by my own feelings—not yet able to understand how someone who looked so much like me could feel so different.

Alone, I watched his group of friends and wondered how I could be more like them.

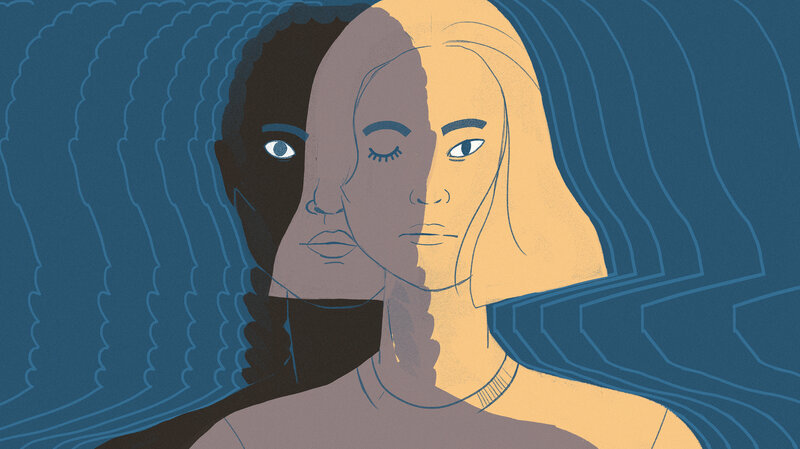

For as long as I can remember, I’ve struggled to figure out what being Asian American is supposed to mean. What I learned early on is that it’s defined by liminality—always positioned in reference to another, more dominant culture; it rarely feels distinct and coherent enough to stand alone.

Being Asian in America means being part of one of the most diverse and racial groups in the country. Unlike members of most other minority communities in the U.S., my racial makeup alone—half-Indonesian, half-Chinese—determines very little about the spaces and environments in which I’ll end up. In fact, Asian Americans are the least likely of all minorities to live in homogenous neighborhoods—while the average white American often resides in neighborhoods that are 75% white and nearly 75% of Black Americans attend majority minority schools. We have the largest income gap of all ethnicities in the country. All this fluidity means we’re uniquely flexible—easily able to both disappear into privilege or to stand with the oppressed.

It’s long been unclear where Asian Americans stand within America’s Black-white binary—a racial paradigm that’s existed for centuries. In “Latinos/as, Asian Americans, and the Black-White Binary,” scholar Linda Martin Alcoff notes that the first time “Black” and “white” were defined in the U.S. was through an 1854 Supreme Court case. That year, George Hall—a white man—was convicted of murder based on the eyewitness testimony of a Chinese American. But Hall’s lawyer argued that Chinese people were simply ancestors of “Indians,” meaning Native Americans, since they were both from Asia—and thus possessed no rights in court.

The Supreme Court took the case a step further and used it to define the Black-white binary: “‘Black’ must mean ‘non-white’ and ‘white’ must exclude all people of color. Thus by law of binary logic, Chinese Americans, after having become Native American, then also became black,” Alcoff writes.

Over the next 150 years after that ruling, Chinese Americans continued to be tossed—both in legislation and in practice—onto either side of the binary, until officially determined by the U.S. Supreme Court to be “non-white” in 1927. According to Alcoff, the Black-white paradigm has long prevented many ethnic groups from defining their own identity.

Today, that inability to self-define still lingers. And many, including myself at times, turn to assimilation—sometimes veering into appropriation—to reconcile it. Growing up without many examples of Asian-American identity, I watched many of my friends and family get pulled toward either whiteness or Blackness in place of developing their own cultural belonging. Chinese girls at my middle school highlighted their hair and pretended not to know Cantonese. Indian boys at my high school wore snapbacks and blasted Kendrick’s Good Kid, M.A.A.D. City.

A brief look at prominent Asian-American figures in pop culture offers further proof of this phenomenon: Eddie Huang—a chef and author who’s been criticized for his insensitive comments about Asian men being so emasculated in America that they’re “basically treated like Black women”—has expressed how, throughout his life, he’s felt like an outsider in both Chinese and White-American culture. Instead, growing up, Huang said he identified much more closely with Blackness. Meanwhile, Queens, NY-raised actress and rapper Awkwafina came under fire last year for her use of a “blaccent” in Crazy Rich Asians. Some fans defended her mannerisms as a byproduct of growing up around Black communities, but critics argued that her persona was performative. And in 2018, Asian-American hip-hop collective 88Rising made waves as a breakthrough force in broadening Asian presence in music. But the collective has also been criticized for its cultural insensitivity—like Rich Brian originally going by “Rich Chigga.”

On the other side of the spectrum, many Asian Americans have sided with the predominantly white movement to strike down Affirmative Action in universities—disenfranchising Black, Latinx, and even Southeast Asian communities in the process. Certain Chinese Americans called the 2014 indictment of police officer Peter Liang in the fatal shooting of Akai Gurley “scapegoating,” implying that Chinese Americans should be afforded “all the privileges offered a white cop who had taken the life of a Black person,” as AAPI scholar Jeff Chang wrote in his 2016 book We Gon’ Be Alright. And despite frequent talk about dismantling the “model minority” myth today, few know that East-Asian Americans actually helped originate that stereotype—intentionally portraying themselves as “upstanding citizens” who could assimilate into the white mainstream of 1940s postwar America.

But where, in all this, is the part that’s distinctly ours? Where does the binary end, and where do we begin?

“I think a lot of younger folks right now are much more aware of the need to place themselves in [America’s landscape],” Jeff Chang tells me. “And it raises these questions: How are we gonna choose to make ourselves visible? When we stand, who do we stand with? I think that those issues are much more front of mind for your generation than it was for mine, who was just trying to get ourselves heard.”

From first grade until my mid-teens, I felt incredible pressure to act white. My life was separated into two non-intersecting pieces: My home in the San Gabriel Valley, one of the largest Asian enclaves in L.A., and my school in Pasadena, where rich whites dominated the old and new money landscape. I wanted so badly to fit into the latter that I pretended the former didn’t exist.

For years, I didn’t use chopsticks, refused to speak Chinese, tried to wear shoes in my home, never brought leftovers to school, and even claimed to dislike boba. I was embarrassed on the rare occasions friends came over and saw my dad lighting incense or my mom speaking on the phone in Indonesian.

That all started to change when I turned 16 and began roaming Downtown LA’s art scene, meeting Latinx, Filipinx, Black, and even white friends who helped me break out of my racial-binary thinking. Slowly, I shed the Black-white lens by which I defined myself and began to explore what it actually meant to be Asian American. Today, I’m still doing that unlearning, and I’m seeing a broader, cultural unlearning starting to happen alongside me.

Over the last few years, we’ve seen Asian Americans amplifying a distinct cultural identity on an unprecedented scale. Artists like Mitski and Swet Shop Boys are bringing songs about the Asian-American experience into genres like indie and hip-hop. Bao—a Pixar short that explores Asian-American family dynamics through an immigrant mother’s relationship with an animated dumpling—won an Oscar this year. Collectives like Asian-American filmmaking group Wong Fu Productions and those behind AAPI magazines Banana Mag and Slant’d are popping up all over the country. And distinctly Asian-American dishes like Roy Choi and Mark Manguera’s Korean taco are now street food staples.

Boba Guys, a national brand known for its artisanal take on the Taiwanese tapioca-filled drink, is another unmistakably Asian-American product. But when the company first launched in 2011, co-founders Bin Chen and Andrew Chau received a lot of backlash for their Americanized version of boba. “We took it really hard in the beginning when people would say that Boba Guys is not authentic—but then we were like, authentic to what? Andrew’s an Asian kid in New Jersey; I was the only Asian kid in Wharton, Texas. This was our experience,” Chen shares. “We exist in this area between East and West, and we should really celebrate that.”

Perhaps Asian-American identity doesn’t have to be entirely distinct. By nature, the Asian-American experience is an ongoing act of hybridization—and that can be beautifully productive. It doesn’t have to look like assimilation or appropriation, as long as we’re respectful and mutually giving to any marginalized cultures that inform our own.

Chang, a celebrated hip-hop historian, agrees. “You can step into the cypher—and this is something that you see in African-American and Indigenous cultures, that there’s a sense of radical welcome,” Chang says. “And if you’re welcomed into a house, you don’t go in and trash it. You don’t go in and steal things. You acknowledge the welcome, and you recognize the debt that you owe.”

Despite the need for intentionality, there’s no reason that this movement can’t happen authentically. For instance, emerging South-Asian-American pop musician Josephine Shetty—better known as Kohinoorgasm—feels a profound connection to the underground music scene she was brought up in. As she gains traction as an Asian-American artist, she has no plans of leaving behind the marginalized communities that have continually supported her craft. “I love the bands I play with, the spaces I get to be a part of and contribute to. I just feel like, How can I not give them everything I can?” Shetty explains. “I feel like any knowledge I gain, any instrument I buy, any skill that I learn—I have to share with someone who doesn’t have access to that.”

Right now, we’re at a pivotal moment where it feels possible to transcend the age-old immigrant Asian mentality of “scarcity,” as Chen put it, that has historically kept us from supporting others both within and outside of our own community. Rather than hold tightly to what we perceive as ours, we can—and should—share in the abundance with communities around us.

As I grow into my mid-20s, I’m discovering that, for me, finding Asian-American identity means confronting, with care and humility, the in-between of race in America. It means seeing my position not as one defined by lack, but as one rich with the potential for collaboration, solidarity, and giving back. And as we—as a community—start telling our stories at increasingly amplified volumes, I hope that this emerging orientation helps us recognize the power that we possess in defining who we are and who we want to be.

I hope that it helps us find comfort in the liminal, that it helps us, finally, stop seeing ourselves in black and white.

.