By Allissa V. Richardson, Assistant Professor of Journalism, University of Southern California, Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism

The Conversation, July 13, 2020

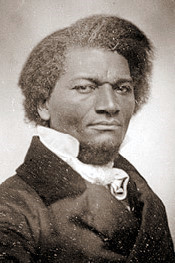

A flashbulb emits a high-pitched hum. A photograph of the legendary 19th-century abolitionist and newspaperman Frederick Douglass fades in on-screen.

We hear the “Hamilton” alumnus actor Daveed Diggs before we see him.

“What, to my people, is the Fourth of July?” Diggs asks in a plaintive voiceover, as a police siren and the opening chords of Jimi Hendrix’s rendition of “The Star Spangled Banner” clash aurally.

In just two minutes and 19 seconds, the new Movement for Black Lives short film provides a highlight reel of African American oppression that spans 400 years.

The juxtapositions are jarring in the Independence Day-themed video. A historic image of a Black toddler picking cotton slams into a modern picture of a masked Black boy marching in protest. Imagery of fireworks at the Lincoln Memorial follows footage of flash grenades being lobbed at protesters. Regal shots of Black soldiers standing in formation dissolve into a forlorn image of a homeless Black veteran.

There is Hurricane Katrina footage. Amy Cooper in Central Parkfootage. Photos of slaves at work. Emmett Till’s remains. Police in riot gear. And so much more.

Perhaps what is most remarkable about this short film, however, is not the sheer volume of source material with which the producers had to work. It’s that this film is rooted in a concept I call “Black witnessing.”

This patriotic form of looking, which documents human rights injustices against Black people, dates back to the days of Frederick Douglass – and it may just be the crowning achievement of the Movement for Black Lives.

What is Black witnessing?

In my book, “Bearing Witness While Black: African Americans, Smartphones and the New Protest #Journalism,” I defined Black witnessing as a defiant, investigative gaze that has three qualities.

First, Black witnessing glares back at authorities in times of crisis or protest, using any available medium that it can to track violence against Black people. In the days of Frederick Douglass, the medium was the slave narrative or the Black newspaper.

During the civil rights movement, Black activists aimed to appear on the 15-minute evening news broadcasts on televisionto highlight sit-ins or marches. Now, freedom fighters have smartphones to capture fatal police encounters or die-in demonstrations.

With these media-making tools, Black witnessing achieves its second characteristic. It forges a historic narrative that links new atrocities against African Americans, such as police brutality, with the original corporeal sins against Black people: slavery and lynching.

Many Americans now may connect the killings of Emmett Till and Trayvon Martin together, for example, even though the boys died more than 50 years apart, since Black witnesses talk about their deaths as part of an ongoing racialized saga, rather than a mere isolated incident.

This spirit carries through the July 4 Movement for Black Lives video too, as it jumps back and forth through time to reimagine Frederick Douglass’ July 5, 1852 speech, “The Meaning of July Fourth for the Negro,” through Daveed Diggs’ poetic voice.

The third quality of modern Black witnessing is that all of these historic narratives – and the viral messaging for which the Movement for Black Lives is so well known – rely on Twitter as its key distribution platform. The social network is like an ad-hoc Black news wire service that bypasses the gatekeeping role of the news media.

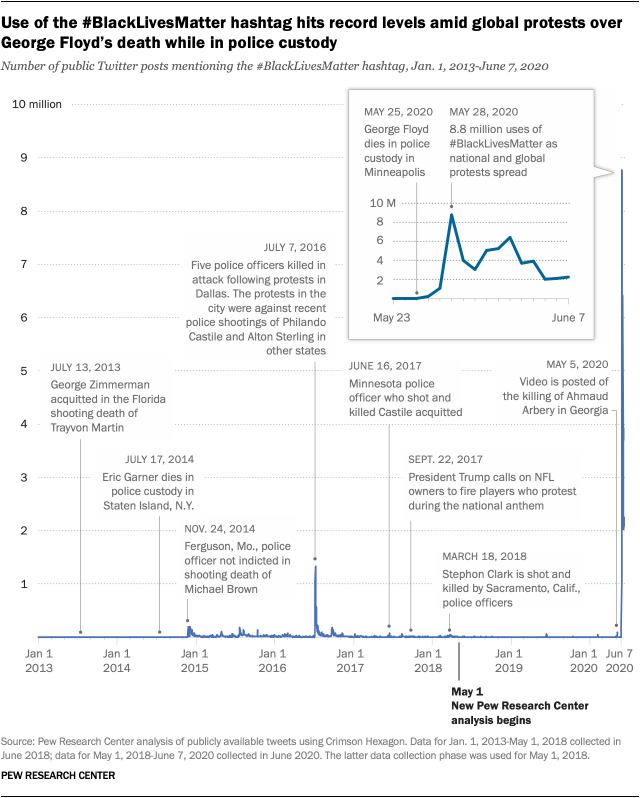

At the height of the George Floyd protests, for example, people tweeted the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter roughly 47.8 million times on Twitter from May 26 to June 7, which represents record level use since the Pew Research Center started tracking the hashtag in 2013.

These data mirror recent polls that indicate 15 million to 26 million people have demonstrated in more than 550 U.S. cities since George Floyd’s death, making Black Lives Matter the largest social movement in U.S. history.

Black witnessing as the responsibility of patriots

In my book I argue that we are living in an era of heightened Black witnessing, the likes of which we have never seen before, thanks to the perfect storm of smartphones, social media and America’s changing attitudes toward racial justice.

During Frederick Douglass’ lifetime, for example, Black slaves could not gaze upon one another as they were being beaten or otherwise punished, lest they incur the wrath of the master themselves.

Similarly, in the days of lynching, there were no Black people on the fringes of the murderous mob photographs.

But now, for the first time, African Americans can use their smartphones to be there, physically, in a moment of shared trauma. Though it is excruciatingly painful to hit “record” during a violent police encounter, the Black witness is saying to the victim: “I will not leave you alone in your final moments. I will tell your family what happened. I will hold police accountable. I will say your name.”

Independence Day 2020 was the perfect time to reevaluate what all of the Black witnesses of centuries past have tried to tell America. From slave narratives to smartphones, they have highlighted the cruel hypocrisy that exists when the country celebrates freedom for some in the U.S., and bondage for others.

The Movement for Black Lives video is a true exercise in Black witnessing. It glares back at the July 4 national holiday. It’s gone viral on Twitter and YouTube. And it connects our nation’s current moment to Frederick Douglass’ 1852 speech. He delivered it to the Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society in Rochester, New York, amid a record-breaking, statewide heat wave.

As Douglass gazed around the room at his audience on that day, I like to imagine that he dabbed sweat from his brow before he exhorted: “What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? … This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

By the time Douglass finished his fiery oration, he used the word “witness” himself, pledging never to leave the work of abolishing slavery in his lifetime. He added: “Allow me to say, in conclusion, notwithstanding the dark picture I have this day presented, of the state of the nation, I do not despair of this country.”

Black witnessing, therefore, is not a denouncement of one’s patriotism; it is an exercise of it. When African Americans press “record” to film police brutality, they are calling for accountability. They are standing in the gap for the dead, who can no longer speak. And they are, perhaps most importantly, challenging a nation not to look away.

###

Allissa V. Richardson is an assistant professor of journalism at the USC Annenberg School for Communication and Journalism. Richardson holds a PhD in journalism studies from the University of Maryland College Park; a master’s degree in magazine publishing from Northwestern University’s Medill School; and a bachelor of science in biology from Xavier University of Louisiana.

Disclosure Statement: Allissa V. Richardson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.