Seth W. Stoughton, University of South Carolina

The murder trial of three men accused in the death of unarmed Black jogger Ahmaud Arbery gets underway on Oct. 18, 2021, with the issue of what makes for a lawful citizen’s arrest set to be central to court arguments.

Arbery was shot dead on Feb, 23, 2020, after being pursued through a residential area of Brunswick, Georgia.

The three men accused in his killing – Greg McMichael, Travis McMichael and William Bryan – contend that they had reason to believe Arbery was responsible for home break-ins in the area. Arbery, they claim, was shot as he tried to resist a legal citizen’s arrest by wrestling a shotgun from Travis McMichael.

Whether the defendants acted lawfully will depend, in large part, on the strength of their citizen’s arrest claim. At a pretrial hearing in July, prosecutors noted that Arbery was not carrying anything at the time of his death. They are expected to argue in the trial that there was no grounds for an attempted citizen’s arrest.

The controversy surrounding Arbery’s killing led to the repeal of Georgia’s almost-150-year-old citizen’s arrest law. But as a law professor and former police officer, I’m aware that most states retain similar, outdated laws that set the stage for vigilantism.

From ‘vigilant Snorers’ to police officers

So-called “citizen’s arrest” laws, which allow private individuals to apprehend an alleged wrongdoer, have been around for centuries. Such laws protect people from civil or criminal liability in the event they “arrest” someone.

In theory, that makes sense. Public safety is everyone’s responsibility, after all. In practice, however, citizen’s arrest doctrines have set the stage for tragic, unnecessary and avoidable confrontations and deaths.

Modern citizen’s arrest rules can be traced back to 1285, when England’s Statute of Winchester directed that citizens “not spare any nor conceal any felonies” and commanded that citizens bring “fresh suit” – prosecute – whenever they see “robberies and felonies committed.”

Back then, there was no “law enforcement” as we understand it today – no cops, no prosecutors. It was largely left to private citizens to apprehend and prosecute felons.

Prior to the development of professionalized police agencies in the mid- to late-1800s, there was no particular legal distinction between arrests made by private citizens and those made by public officials.

In English cities and larger towns, able-bodied men were expected to take generally unpaid shifts patrolling as night watchmen. Watchmen were often conscripted, and citizens of means could hire someone to serve on their behalf, resulting in a dubious dedication to duty.

This practice extended beyond England to its colonies. An account published in the New York Gazette in the mid-18th century described night watchmen as “a parcel of idle, drinking, vigilant Snorers, who never quelled any nocturnal Tumult in their Lives.”

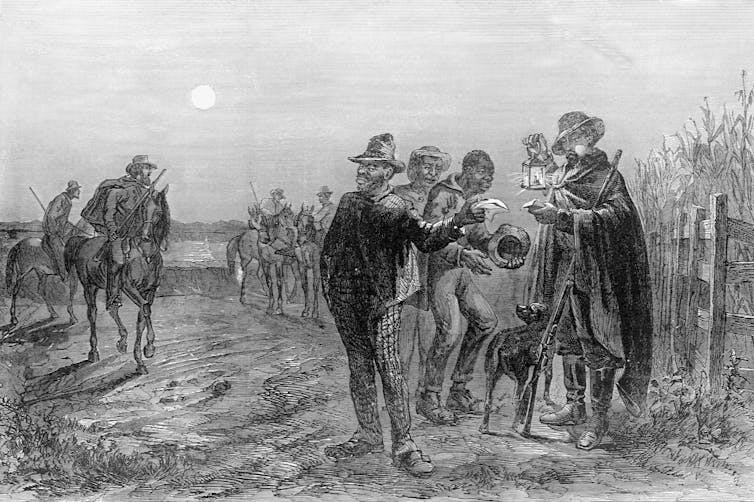

When watchmen did take action, they often did so in problematic ways. In New England, that often involved enforcing the ethnic segregation between different neighborhoods. In the mid-1600s, the slave codes of the colonial American South declared that controlling the enslaved population was a matter of public responsibility – the “public” here being exclusively white men. Paid and volunteer militiamen were tasked with, as the author Kristian Williams has noted, “making regular patrols to catch runaways, prevent slave gatherings, search slave quarters … and generally intimidate the black population.”

Shopkeeper’s privilege and security guards

Today more than 18,000 local, state and federal agencies provide police services in the U.S. But citizen’s arrest lives on in the form of a national patchwork of statutes and common law doctrines.

Most states have “shopkeeper’s privilege” laws that provide a defense for business owners and employees who arrest someone for theft so long as they have probable cause. Resisting such an arrest is a crime in some states. Private security guards, similarly, may be authorized to make arrests, at least on the property they are hired to protect. And when bounty hunters capture someone who has jumped bail, the Supreme Court has said the arrest “is likened to the rearrest by the sheriff of an escaping prisoner.”

Those who are not a shopkeeper, security guard or bounty hunter may still be able to effect an arrest under more generic citizen’s arrest rules.

Citizen’s arrest rules are not the same as the legal rules that govern arrests by police officers. In some ways, private individuals have more limited authority to make arrests than officers.

In many states, for example, an officer can make arrests for offenses classified as misdemeanors – minor crimes typically punishable by up to a year in jail – but a private citizen cannot.

In other states, a private citizen may make an arrest only if they witness or have firsthand knowledge of an offense. This was the case in Georgia, at least with regard to misdemeanor crimes, until public pressure after Arbery’s death led to the 2021 repeal of the state’s citizen’s arrest statute. Under the laws in effect at the time, Arbery’s pursuers would only have been able to make a citizen’s arrest if they had probable cause to believe that he had committed a felony.

In a similar vein, some states only permit individuals to invoke “citizen’s arrest” as a defense to civil or criminal liability if the person they arrested actually committed an offense, while officers are protected if they had probable cause to believe that the person committed an offense (even if that belief was incorrect).

But in other ways, private actors have more authority than officers do. Perhaps most obviously, the constitutional rules that limit police authority to conduct searches, seizures, and interrogations do not apply when “a private party … commits the offending act.”

Citizens may have more authority to use force than law officers, too, depending on state law.

In South Carolina, a citizen can use deadly force to effect the nighttime arrest of someone who has any stolen property in their possession or, more problematically, someone who “flees when he is hailed” if the circumstances “raise just suspicion of his design to steal.”

If an officer in South Carolina did the same, he would likely run afoul of state law or the Fourth Amendment, which the Supreme Court has held requires probable cause “that the suspect poses a significant threat of death or serious physical injury.”

Race and status

No one knows how many citizen’s arrests occur in the U.S. every year because the police are usually called and an officer processes the arrest, leaving little evidence of private involvement.

We do know, however, that private arrest authority is too often badly misused by those who believe their higher social status gives them authority over someone they perceive as having lower status.

Frequently, this falls along racial lines, as seen in the detention of immigrants by militias at the U.S. border, the attitude of nightwatchmen in gated communities, and in situations like the Arbery case.

The three defendants say they chased Arbery because they believed he was behind neighborhood burglaries and allege they saw him trespass prior to the incident. Arbery, of course, had committed no crime; under Georgia’s “criminal trespass” law, entry onto “land or premises,” including a construction site, is only a crime when committed “with an unlawful purpose” or when there are posted “No Trespassing” signs. There is no evidence of either in this case.

[Over 115,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

And even if Arbery had committed a burglary, his death would have still been the result of an unjustified act of vigilantism. As the Supreme Court has said in the context of police uses of force, “It is not better that all felony suspects die than that they escape.” Remembering that as the U.S. considers reforming citizen’s arrest statutes may go a long way in preventing any further unnecessary deaths.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on May 29, 2020.

Seth W. Stoughton, Associate Professor of Law, University of South Carolina

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.