Pedro A. Noguera, University of Southern California

Nearly seven decades after the U.S. Supreme Court’s unanimous landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, the court’s declared goal of integrated education is still not yet achieved.

American society continues to grow more racially and ethnically diverse. But many of the nation’s public K-12 schools are not well integrated and are instead predominantly attended by students of one race or another.

As an educational sociologist, I fear that the nation has effectively decided that it’s simply not worth continuing to pursue the goals of Brown. I also fear that accepting failure could portend a return to the days of the case that Brown overturned, the 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision. That case set “separate but equal” facilities for different races, including schools and universities, as the national priority.

The Brown decision was based upon a repudiation of that idea and the recognition that “separate but equal” was never achieved. I remain convinced it never will be.

A historic push

In many ways, it would be startling to declare the ideal of integrated schooling a lost cause. Integration was so important in 1957 that Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower sent federal troops to Little Rock, Arkansas, to ensure that nine Black students were safe when they enrolled in the city’s Central High School.

Despite the federal government’s intervention, in the 1960s and 1970s, many communities across the U.S. experienced considerable conflict and even bloodshed. Many white citizens actively and violently opposed school integration, which often came in the form of court-mandated busing of Black students to schools in predominantly white neighborhoods.

Despite the opposition, many Americans worked incredibly hard to make integration happen, and its benefits are clear: Many American children have experienced enhanced educational opportunities and improved academic success as a result of these efforts.

Separated, if not segregated

However, in 2018-2019, the most recent school year for which data is available, 42% of Black students attended majority-Black schools, and 56% of Hispanic students attended majority-Hispanic schools. Even more striking, 79% of white students in America went to majority-white schools during the same period.

Those statistics signal the existence of what is, in fact, a racially separate educational system. But these statistics about race don’t show how common separation by socioeconomic status is in most urban schools throughout the U.S. Low-income Black and Hispanic students are most likely to attend schools where the majority of children are poor and the resources available to serve them are inadequate.

Since 2001, education policymakers have made bold promises to close what has been called the “racial achievement gap.” Yet they have largely ignored the fact that throughout the nation, poor children of color are most likely to attend schools where they are not only separated by race and class, but where the quality of the education they receive is below that of their white peers.

Housing and school choices

Several factors help to explain the degree of race and class separation and educational inequality that is now pervasive in America. To begin with, many communities throughout the United States continue to be characterized by a high degree of racial and socioeconomic separation. However, while residential patterns pose an obstacle, a 2018 study by the Urban Institute found that neighborhood segregation does not in itself explain current patterns of school segregation. The study identified several cities and suburban communities where schools are significantly more segregated than the neighborhoods in which they are located.

Policies that allow parents to choose which of their district’s public schools their children attend have done little to alter these trends and, in fact, may contribute to the problem. Several studies have shown that public charter schools are more likely to be intensely racially divided than traditional public schools.

Furthermore, in most major American cities, affluent residents are more likely to enroll their children in private schools than public schools. This includes many affluent parents of color, who often choose to enroll their children in predominantly white independent schools in search of a better education, even when their children experience race-related microaggressions and alienation.

In the past 20 years, cities such as Boston, New York, Denver, Washington, D.C., and Seattle have seen affluent white populations increase – but the overwhelming majority of students in those cities’ public schools are from low-income Black and Hispanic households. Those sorts of racial imbalances have increasingly become the norm.

Integration can succeed

When the poorest and most vulnerable children are concentrated into particular schools, it is even more difficult to achieve racial equality in educational opportunity, either through integration as called for by Brown or by pursuing “separate but equal” as called for by Plessy.

There is good reason to be concerned. For decades there has been consistent evidence that when schools serve a disproportionate number of children in poverty, they are less likely to improve students’ academic success.

The evidence also shows that when Black and Hispanic children attend racially integrated schools, they tend to outperform their peers who do not. For example, students who have participated in the Metco program, a voluntary desegregation effort that makes it possible for children of color from Boston to be bused to affluent schools in the suburbs, have fared better academically than their counterparts who remained in Boston’s racially isolated schools. The research doesn’t show whether that is because of the superior resources available in predominantly white suburban schools or the fact that they have parents who are active enough to get them into suburban schools. It may be that both factors play a role.

A 2018 study from UCLA found that all the schools that produce significant numbers of Black students who are eligible for admission to the University of California are racially integrated. Unfortunately, the study also found that most Black students in Los Angeles don’t attend integrated schools.

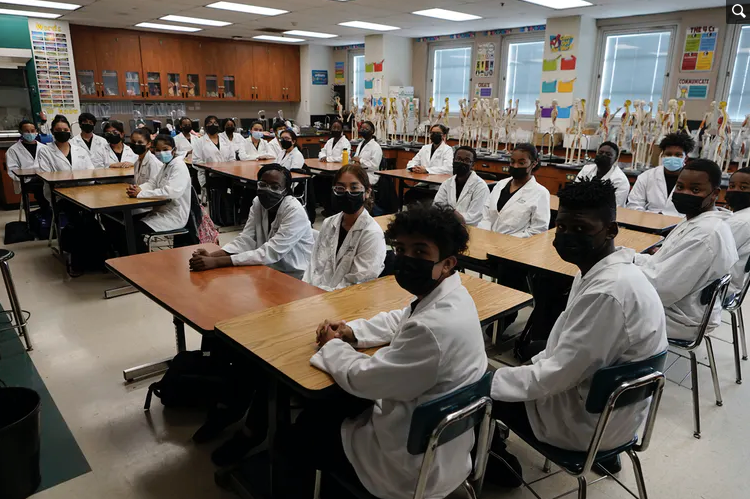

However, the study also found one notable exception: the King/Drew Health Sciences Magnet High School of Medicine and Science in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles. That school, which serves almost exclusively Black and Hispanic students, sends more Black students to the University of California than any other high school in the state of California.

At King/Drew, students have a rigorous, enriched education that includes many honors and Advanced Placement courses. Those opportunities are the norm at many affluent suburban schools, but they are rare at public schools in urban areas.

The scarcity of schools like King/Drew – well-resourced and serving a low-income or majority-minority student body – should serve as a reminder that racially separate schools are rarely equal. When Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP took the Brown case, they knew that funding for education generally followed white students.

That was true in 1954, and it is largely true today. A recent study found that nonwhite school districts in the U.S. receive US$23 billion less in funding than predominantly white schools, though they serve the same number of students.

For this reason, on the occasion of the 68th anniversary of the Brown decision, I believe it is important to remember why and how civil rights and educational opportunity remain so deeply intertwined. Despite its flaws and limitations, the effort to racially integrate the nation’s schools has been and continues to be important given the type of pluralistic and diverse nation the U.S. is becoming. It also plays a central role in the ongoing pursuit of racial equality.

Pedro A. Noguera, Dean, USC Rossier School of Education, University of Southern California

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.