A study by Washington University researchers found that working women who want to reduce career income losses related to motherhood should wait until they are about 30 years old before having children.

By Kristina Sauerwein And Gerry Everding

PHYS.org, April 14, 2016 —

Credit: Thinkstock

Working women who want to minimize career income losses related to motherhood should wait until they are about 30 years old to have their first children, suggests new research from Washington University in St. Louis.

The findings, published in PLOS ONE, hold true regardless of whether a woman has earned a college degree.

For college graduates and those without a college degree, the researchers found lower lifetime incomes for women who gave birth for the first time at age 30 or younger. The hit was particularly stark for women without college degrees who had their first children before age 25.

“The findings highlight the financial trade-offs women make when considering their fertility and career decisions,” said Man Yee (Mallory) Leung, a postdoctoral research associate at Washington University School of Medicine. “Other studies have focused on the effect of children on women’s wages, but ours is the first to look at total labor income from ages 25 to 60 as it relates to a woman’s age when she has her first baby.”

For this study, Leung and colleagues analyzed work experience, birth statistics and other household data of nearly 1.6 million Danish women ages 25-60 from 1995 to 2009 to estimate how a woman’s lifetime earnings are influenced by her age at birth of first child.

Study co-authors are Raul Santaeulalia-Llopis, assistant professor of economics in Arts & Sciences at Washington University, and Fane Groes, an economics professor with the Copenhagen Business School in Denmark.

Denmark is a gold mine for researchers because the nation collects socioeconomic and health register data on 100 percent of the population. The Danish experience supports the notion that children can substantially affect the potential career path of their mothers.

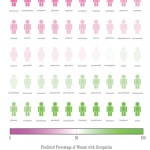

Credit: CDC/NCHS, National Vital Statistics System

“Children do not kill careers, but the earlier children arrive the more their mother’s income suffers. There is a clear incentive for delaying,” said Santaeulalia-Llopis. “Our main result is that mothers lose between 2 and 2.5 years of their labor income if they have their first children before the age of 25.”

Researchers arrived at these estimates by calculating average annual salaries for each woman and using this average as a measuring stick for both short- and long-term income losses associated with age at birth of first child. Income losses were estimated for women who had their first children before age 25 and for each subsequent three-year age range (ie. 25-to-28), with the last range being 40 years of age or older.

Other findings include:

– College-educated women who had children before age 25 lose about two full years of average annual salary over their careers; women in this category with no college degree lose even more, forgoing about 2.5 years of average annual salary during their working careers.

– Women who first give birth before age 28, regardless of college education, consistently earn less throughout their careers than similarly educated women with no children.

– College-educated women who delay having their first children until after age 31 earn more over their entire careers than women with no children.

– Noncollege-educated women who give birth after age 28 experience a short-term loss in income but eventually catch up with the lifetime earnings of women who have no children. Those who delay their first children until age 37 add about a half year of salary to lifetime earnings.

– In terms of short-term income loss, women with no college education take a greater hit than their college-educated counterparts in almost every age range, with one notable exception those who first give birth from ages 28 to 31.

– Here, college-educated women experience income losses equal to 65 percent of average salary, compared with 53 percent for women with no degree. Both groups lose less short-term income the longer they delay having their first children.

The researchers noted these income trends while studying the effects of in vitro fertilization on women’s labor and fertility choices. Here, they found a general shift toward women having a first child later in life, with a greater proportion of college-educated women pushing first birth into the 28-34 age range.

“The emergence of IVF technology has a significant impact on labor trends,” said Leung, who has a doctorate in economics.

As this trend progresses, more women will have the option to consider delaying motherhood until later in their careers, a choice that can have significant impact on lifetime earning potential, the researchers suggest.

The impact of age at first birth on lifetime earnings may be even more dramatic in countries such as the United States, where women generally receive 12 weeks of unpaid leave. Denmark’s more generous policies provide new mothers with up to 18 months of paid maternity leave.

“The fact that highly productive women who have children earlier enter a lower income path is not only a loss for them, but for the entire society,” said Santaeulalia-Llopis. “If children are shutting down women’s career growth and these pervasive effects vanish after the mid-30s, then we should start taking seriously the case for employer-covered fertility treatments. But we need to dig deeper to establish causation and assess costs and benefits.”