By Robert Gudmestad, Professor and Chair of History Department, Colorado State University

The Conversation, January 25, 2021

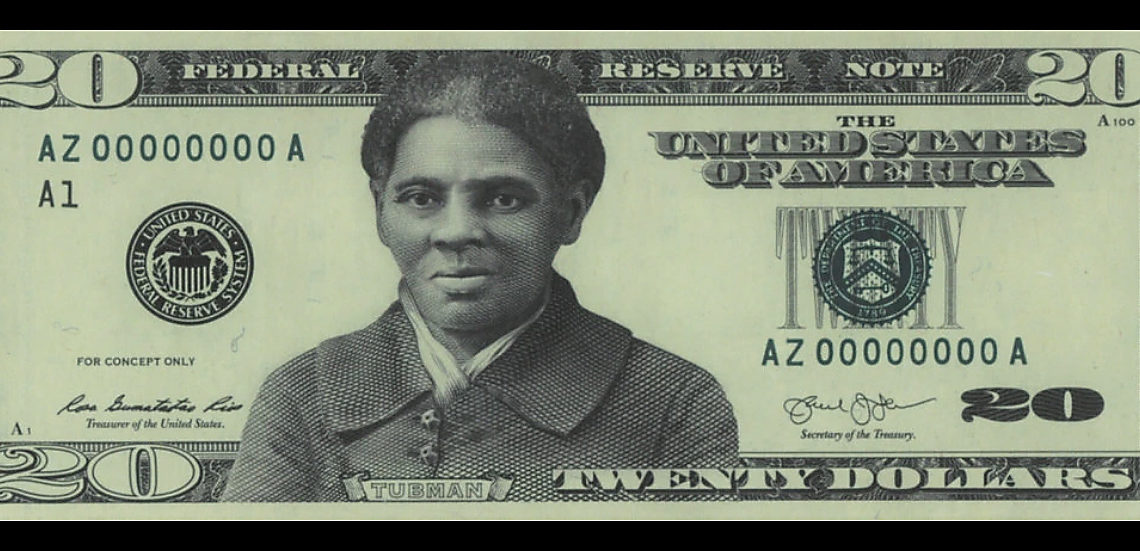

The Biden administration has revived a plan to put Harriet Tubman on the US$20 bill after Donald Trump’s Treasury secretary delayed the move.

That’s encouraging news to the millions of people who have expressed support for

putting her face on the bill. But many still aren’t familiar with the story of Tubman’s life, which was chronicled in a 2019 film, “Harriet.”

Harriet Tubman worked as a slave, spy and eventually an abolitionist. What I find most fascinating, as a historian of American slavery, is how her belief in God helped Tubman remain fearless, even when she came face to face with many challenges.

Tubman’s early life

Tubman was born Araminta Ross in 1822 on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. When interviewed later in life, Tubman said she started working as a housemaid when she was 5. She recalled that she endured whippings, starvation and hard work even before she got to her teenage years.

She labored in Maryland’s tobacco fields, but things started to change when farmers switched their main crop to wheat.

Grain required less labor, so slave owners began to sell their enslaved people to plantation owners in the Deep South.

Two of Tubman’s sisters were sold to a slave trader. One had to leave her child behind. Tubman, too, lived in fear of being sold.

When she was 22, Tubman married a free black man named John Tubman. For reasons that are unclear, she changed her name, taking her mother’s first name and her husband’s last name. Her marriage did not change her status as an enslaved person.

Five years later, rumors circulated in the slave community that slave traders were once again prowling through the Eastern Shore. Tubman decided to seize her freedom rather than face the terror of being chained with other slaves to be carried away, often referred to as the “chain gang.”

Tubman stole into the woods and, with the help of some members of the Underground Railroad, walked the 90 miles to Philadelphia, where slavery was illegal. The Underground Railroad was a loose network of African Americans and whites who helped fugitive slaves escape to a free state or to Canada. Tubman began working with William Still, an African American clerk from Philadelphia, who helped slaves find freedom.

Tubman led about a dozen rescue missions that freed about 60 to 80 people. She normally rescued people in the winter, when the long dark nights provided cover, and she often adopted some type of disguise. Even though she was the only “conductor” on rescue missions, she depended on a few houses connected with the Underground Railroad for shelter. She never lost a person escaping with her and won the nickname of Moses for leading so many people to “the promised land,” or freedom.

After the Civil War began, Tubman volunteered to serve as a spy and scout for the Union Army. She ended up in South Carolina, where she helped lead a military mission up the Combahee River. Located about halfway between Savannah, Georgia, and Charleston, South Carolina, the river was lined with a number of valuable plantations that the Union Army wanted to destroy.

Tubman helped guide three Union steamboats around Confederate mines and then helped about 750 enslaved people escape with the federal troops.

She was the only woman to lead men into combat during the Civil War. After the war, she moved to New York and was active in campaigning for equal rights for women. She died in 1913 at the age of 90.

Tubman’s faith

Tubman’s Christian faith tied all of these remarkable achievements together.

She grew up during the Second Great Awakening, which was a Protestant religious revival in the United States. Preachers took the gospel of evangelical Christianity from place to place, and church membership flourished. Christians at this time believed that they needed to reform America to usher in Christ’s second coming.

A number of Black female preachers preached the message of revival and sanctification on Maryland’s Eastern Shore. Jarena Lee was the first authorized female preacher in the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

It is not clear whether Tubman attended any of Lee’s camp meetings, but she was inspired by the evangelist. She came to understand that women could hold religious authority.

Historian Kate Clifford Larson believes that Tubman drew from a variety of Christian denominations, including the African Methodist Episcopal, Baptist and Catholic beliefs. Like many enslaved people, her belief system fused Christian and African beliefs.

Her belief that there was no separation between the physical and spiritual worlds was a direct result of African religious practices. Tubman literally believed that she moved between a physical existence and a spiritual experience where she sometimes flew over the land.

An enslaved person who trusted Tubman to help him escape simply noted that Tubman had “de charm,” or God’s protection. Charms or amulets were strongly associated with African religious beliefs.

An injury becomes a spiritual gift

A horrific accident is believed to have brought Tubman closer to God and reinforced her Christian worldview. Sarah Bradford, a 19th-century writer who conducted interviews with Tubman and several of her associates, found the deep role faith played in her life.

When she was a teenager, Tubman happened to be at a dry goods store when an overseer was trying to capture an enslaved person who had left his slave labor camp without permission. The angry man threw a 2-pound weight at the runaway but hit Tubman instead, crushing part of her skull. For two days she lingered between life and death.

The injury almost certainly gave her temporal lobe epilepsy. As a result, she would have splitting headaches, fall asleep without notice, even during conversations, and have dreamlike trances.

As Bradford documents, Tubman believed that her trances and visions were God’s revelation and evidence of his direct involvement in her life. One abolitionist told Bradford that Tubman “talked with God, and he talked with her every day of her life.”

According to Larson, this confidence in providential guidance and protection helped make Tubman fearless. Standing only 5 feet tall, she had an air of authority that demanded respect.

Once Tubman told Bradford that when she was leading two “stout” men to freedom, she believed that “God told her to stop” and leave the road. She led the scared and reluctant men through an icy stream – and to freedom.

Harriet Tubman once said that slavery was “the next thing to hell.” She helped many transcend that hell.

###

Disclosure statement: Robert Gudmestad does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.