By Nanct Lopez

The Conversation, February 28, 2018 —

If you were walking down the street, what race would strangers automatically assume you were?

What’s your ‘street race’? blvdone/shutterstock.com

“Street race” – what race you look like, based on your skin color, facial features and more – is an important aspect of a person’s experiences. For example, research shows that a person who’s Hispanic but perceived as light-skinned does not experience the same level of discrimination as a Hispanic person who’s seen as darker-skinned.

However, the U.S. census does not clearly capture these differences. In past surveys – and in the upcoming 2020 census – the Census Bureau boils complex information on race, ethnicity and ancestry into just two questions: “Are you of Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin?” and “What is your race?”

As a sociologist who specializes in research on social inequalities, I believe this way of capturing race and ethnicity undermines the country’s ability to serve vulnerable communities. Without reliable data, it’s difficult to track whether Americans of different colors and backgrounds receive equitable opportunities in housing, voting, employment or education.

Confusing race and ethnicity

Every 10 years, the U.S. Census Bureau undertakes a count of the U.S. population. Since 1790, this has included some sort of data on race and ethnicity.

Ahead of the 2020 census, there has been much debate over potential formats that would have combined “race” or “origin” in one question. Proponents argued that doing so would provide granular data on the ancestries of all groups and reduce the high number of Hispanic origin people who check off “some other race.” Opponents argued that this would have made it much more difficult to track inequalities in the Latino community, because the census would no longer capture race separately from other aspects of a person’s national origin or ethnic background.

On Jan. 26, the Census Bureau announced that it would keep longstanding questions on Hispanic origin and race separate for the 2020 census.

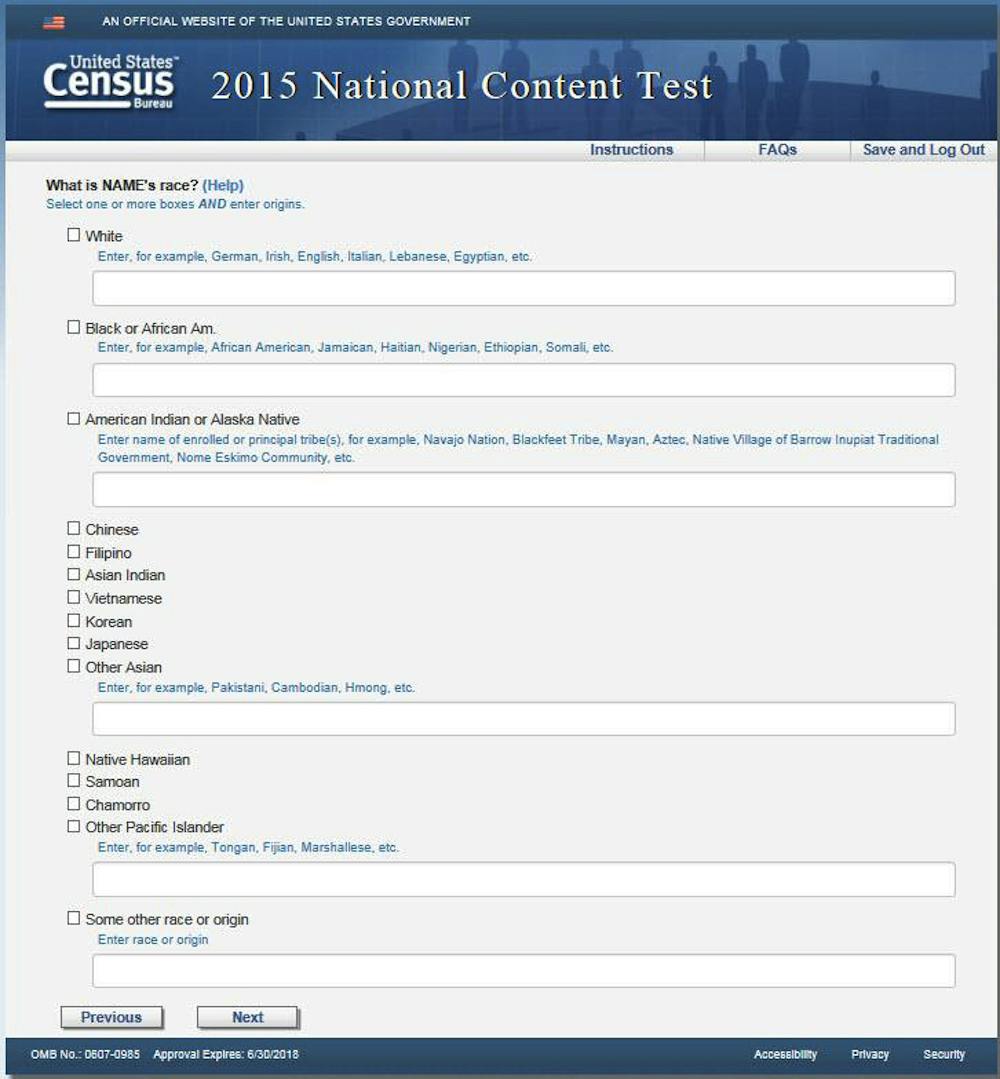

The suggested format, unlike others before it, links specific origins under each race box. For example, under the “White” race box, the survey lists sample ancestries such as German, Irish, English and Italian. The “Black” race box suggests “African American, Jamaican, Haitian, Nigerian, Ethiopian, Somali, etc.” Respondents can mark one or more race boxes.

Although this is a step in the right direction, the chosen wording is still problematic. With the exception of the race box for “American Indian,” not a single other race box contains a Hispanic origin ethnicity. This will create confusion for many.

National origin doesn’t predict race

By not including a single Hispanic origin group under the “White” or “Black” race box, the 2020 census inadvertently contributes to the false idea that people of Hispanic origin are all of the same race or color.

But Latin America and the Caribbean were the site of European colonization of Native American communities and the enslavement of Africans forcibly transported to the Americas. There are white, black and Native American Hispanics.

The American Community Survey, an annual survey administered by the Census Bureau to over a million households annually, already asks a separate question on ancestry. From my conversations with census designers, I understand that they are mechanistically reporting the ancestries most commonly reported for a given race in this survey. But, in doing so, they may inadvertently contribute to the falsehood that ethnicity predicts one’s race.

The logic behind correlating nationalities with designated racial groups just does not hold. Are all South Africans and Canadians white? Aren’t Asian people who were born and raised in France ethnically French? Following this logic, all national origins should be associated with a given race. If this is the case, where should we list “American” ethnicity?

More importantly, this approach may unintentionally contributing to the false and dangerous idea that some racial groups are the more “authentic” representatives of a given national origin. National origins and race should never be linked.

Census designers have also argued that including a space for ethnicity under each race box gives everyone an opportunity to recognize their unique ethnic origins. For example, anyone checking their race as white can designate that they are of German or Irish background.

This approach might appear to be equal, but it doesn’t take into account how color affects people seen as brown or black throughout history. Research shows that Hispanics who appear European or white are less likely to experience voting or housing discrimination. They also outearn their darker-skinned counterparts who are at the same level of education, of the same ethnic background or even in the same families.

In short, your multiple ancestral, geographic or ethnic origins may not matter as much as your “street race” when you show up to look at an apartment or apply for a job.

Former President Barack Obama, for example, was chided for not checking both the white and black race boxes and instead marking his race solely as “Black” on the 2010 census. Critics argued that he was denying his European ancestry. My guess is that Obama understood that these data are used to examine inequalities that have much more to do with “street race” than with whatever ethnic, familial or genetic origins one may have.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, where there’s still a strong racial hierarchy, a number of countries are beginning to separate questions on race from questions on ethnicity and origin from questions on national origin or ethnicity.

New questions for advancing justice

Where do we go from here? It’s too late to change the wording for the 2020 census, but it’s worth imagining what the 2030 census might look like. As the U.S. population becomes increasing more diverse, measuring injustice along the color line will be more important than ever.

More complex questions would clarify that when we are asking about race we are asking about color, and that when we are asking about ethnicity we are asking about national origins, familial or ancestral origins. That could go a long way toward improving researchers’ and activists’ ability to document social inequalities faced by visible minorities – those most likely to suffer discrimination.

In my view, a truly ethical and equitable census would educate the general public about the difference between race or color and ethnicity. It would also include at least three separate questions: one on Hispanic origin, one on race or color (or what I call “street race”), and another on familial or ancestral origin or ethnicity.

The Census Bureau is currently discussing a potential separate question on Middle Eastern and North African origin in the 2030 census. If the 2030 census designers do decide to test this question again, I hope they maintain it as separate from the race on the questionnaire. This would allow researchers to examine if people of this geographic origin, who mark their race as white, experience the same levels of residential segregation as those who may check “Black” or another race.

The difference between street race, ethnicity and ancestral origin is real and tangibly shapes people’s experiences with injustice. Flattening these differences in our federal, state and local data will impede equitable opportunities in voting, housing, employment, education and health care. Smarter questions could advance justice and equity and help create a more perfect union for all.