By Kristen Carlson, Associate Professor of Law and Adjunct Associate Professor of Political Science, Wayne State University

The Conversation, March 25, 2020

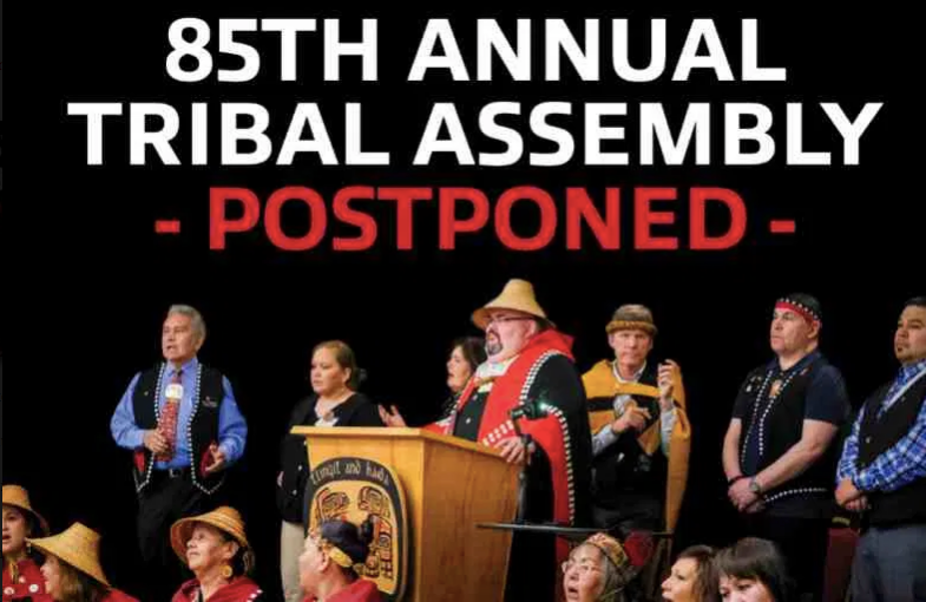

The coronavirus is hitting American Indians and Alaska Natives hard. Tribal citizens are dying, Indian nations have closed casinos to protect the public, and powwows and traditional gatherings have been canceled.

Among the crucial statistics that indicate how dire conditions are for American Indians and Alaska Natives: Indian Health Service hospitals have only 625 beds nationwide, with six intensive care unit beds and 10 ventilators to serve more than 2.5 million American Indians and Alaska Natives from 574 tribes.

Some tribes provide additional health services in their communities, but these programs only supply another 772 beds. That’s only 1,397 for 2.5 million people.

Governments at all levels have struggled to respond to the coronavirus pandemic as it spreads across the United States.

Tribal leaders have stepped up to protect their communities and prevent the spread of the virus, but they face unique problems in combating this pandemic. And the federal government’s historical and current reluctance to provide adequate resources and money to tribal governments and the Indian Health Service has compounded those problems.

Tribal citizens at great risk

American Indians and Alaska Natives remain the most impoverished and marginalized group in the United States.

Indian tribes have fewer resources than other communities in the U.S. to respond to the crisis. Many Native Americans lack basic access to water, indoor plumbing and adequate housing. Overcrowded housing and homelessness make social distancing difficult, and isolation impossible, for some.

Others do not have access to adequate health care services near their homes on tribal lands. The federally funded Indian Health Service provides health care to over 2.5 million American Indians and Alaska Natives, more than a quarter of whom do not have health insurance.

Native populations also suffer from diabetes, asthma and other chronic illnesses at a higher rate than the U.S. population generally. These health disparities place many American Indians and Alaska Natives at a higher risk to get COVID-19, and have more severe cases of it. An inadequate response to containing the virus may lead to deadly results for many American Indians and Alaska Natives.

Lack of capacity

The Indian Health Service has faced chronic underfunding by Congress since its inception in 1955. Many have criticized the Indian Health Service for poor medical care, high staff turnover and untrained staff.

Like other health facilities, the ones run by the Indian Health Service are short on ventilators, coronavirus tests and personal protective gear for health care providers. Less than half of tribal leaders and health care providers have indicated that they have the capacity to isolate suspected coronavirus patients.

Even if tests and basic medical supplies were available, Indian nations lack the capacity to track the virus and slow its spread. The 12 regional tribal epidemiology centers do not have the relationships necessary with tribal and state health departments to share information about prevalence or mortality rates.

Tribes take action

The pandemic has further compromised Indian nations’ resources because tribal leaders have chosen to close businesses – resorts, retail stores, entertainment venues and casinos – to protect the public.

For Indian nations, this means more than lost profits. The money those businesses make pays for tribal programs and services. Without this money, tribal governments can’t take care of their people.

Despite these challenges, tribal leaders are taking action to protect Native people.

Over 50 tribes have declared emergencies, more than 40 have imposed travel restrictions, dozens are trying to close their borders to slow the spread of the disease, and others have translated information about the virus into their native languages to communicate better with their citizens.

Tribal leaders are also pressing the federal government to respond to the elevated risks faced by Indian nations in this pandemic.

Too little, too late?

The federal government has a trust responsibility to protect Indian nations. Based on its treaty relationship with and respect for the sovereignty of Indian nations, the federal government is obligated to support tribal self-government and economic prosperity and to protect tribal lands, assets and resources.

The federal government has yet to live up to its treaty and trust responsibilities to Indian nations and offer adequate assistance in responding to the coronavirus epidemic.

Enacted on March 6, the Coronavirus Preparedness and Response Supplemental Appropriations Act authorizes US$40 million in emergency aid to help American Indians combat the coronavirus.

But the Trump administration has yet to release the money, and it took over two weeks to devise a plan so that tribal governments and organizations could even access the funds.

The plan adopted by the Trump administration ignored requests from tribal leaders to have the Indian Health Service disseminate the funds, requires tribes to seek noncompetitive grants, and has yet to allocate any money to tribes in some regions.

Tribal leaders continue to pressure the federal government to take the spread of the coronavirus to their communities seriously and provide basic medical supplies, funding for medical services and economic aid to address lost revenues for tribal programs and services due to business closures.

Some members of Congress appear to be paying attention. The House Committee on Natural Resources has initiated efforts to gather information from Native communities about how the coronavirus is affecting them and how the federal government could serve them better.

But Indian leaders remain concerned as the number of cases in Indian country continue to rise. Despite their best efforts, it may turn out that too little aid came too late.

###

Kirsten Carlson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.