By Johanna Weststar, Carolyn Troup, David Peetz, Ioana Ramia, Sean O’Brady, Shalene Werth, Shelagh Campbell, and Susan Ressia

The Conversation, November 4, 2020

How do people really feel about working from home?

Since the COVID-19 pandemic began, there has been lots of talk about how people have reacted to being forced to work from home.

But there hasn’t been much information on what they really think, how they’ve been affected and what will happen from here.

We studied 11,000 employees in Canadian and Australian universities through an online survey. In both countries, most universities shifted much of their work online earlier this year. These are our preliminary results about employee experiences. It’s a mixed picture, but it tells us that a lot of change is ahead and that workers should be part of the discussion about how their workplaces respond to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Universities are made up of a varied workforce — in addition to academic positions, there are administrative and professional roles, similar to those in other organizations in the private and public sectors. Flexible working policies exist in the university sector, but we found that academics experienced working from home differently than those in administrative and professional positions.

Working from home is more common among academics than their professional counterparts, but in general during this period, academics are typically negative about working from home, while administrative and professional employees have had more positive experiences.

Variations in remote work preferences

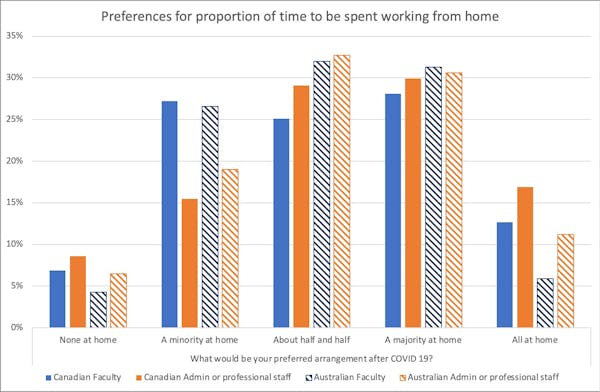

People vary a lot in how much they want to work from home, but one thing is clear — most want to do some of their paid work from home, but few want to work at home all the time.

For about a third of employees in both groups, a roughly 50/50 balance between working from the office and working from home would be ideal. Another two-fifths would like to do a majority of their work at home. Another quarter would like to do only a minority of their work from home. See below:

People in both groups want to work from home more than they did before the pandemic. But general and professional staff in both countries want to increase the amount they work from home more than academics do.

Women want a bit more time working from home than men. And Canadians want a bit more time working at home than Australians, but not by much.

Fewer interruptions

We haven’t yet identified the reasons why some people are positive about their experiences working from home and some are negative. But aside from time and travel savings, we do know that a majority of people find they are interrupted less by others at work because there are fewer people around.

Large majorities (two-thirds to three-quarters) of people in our study say the equipment at home is suitable, they receive adequate support from their university and have a space at home where they can work. For most, their homes provide a pleasant environment.

But not everyone’s happy. Isolation is a significant source of distress, and remote working makes communication more difficult. There is also no shortage of negative comments about equipment and the work set-up at home. A more widespread negative finding regarded working hours. About three-fifths have ended up working more.

For academics, dissatisfaction with working arrangements during the pandemic is worse when they have less experience with online teaching. But this isn’t the only factor.

Even among those who have lots of experience with online teaching, views are evenly split on whether the new work arrangements are a positive or negative experience.

Academic employees

Academic employees end up spending more time meeting their teaching obligations, and also more time on administration or what universities call “service” — especially female academics. Many academics have less time to spend on research. Women, in particular, have less time to finish or submit research papers.

That’s consistent with suggestions from journal editors that women’s submissions to journals have dropped off since the pandemic started.

Academics tend to be concerned about how their performance appraisals will be managed. But administrative and professional employees are much less bothered by this.

Most people have fewer connections with people they work with. But there is less separation between work and home. About two-fifths feel that their work spills over more into their home life, and almost as many feel more spillover from their home life into their working day.

A few feel that these forms of interference have decreased. Nearly half of employees spend more time on domestic responsibilities. Very few spend less time.

Stress has gone up. With all the redundancies happening in universities, especially in Australia, job security has plummeted.

Pluses and minuses

Overall it’s not a simple story. There are pluses and minuses. Working from home has a lot going for it, but it’s also problematic for a lot of people. Generally speaking, there’s no consistent view about what employees want.

As it is, some of the problems aren’t just because of working from home. Online teaching, for example, is a totally different process than face-to-face teaching — it’s not just doing the same work from a different place.

The bottom line is that working from home is too complex for broad managerial edicts to work. Without involving employees and their representatives in decisions, managers could come up with supposed solutions that may be worse than the problems they’re trying to deal with. Some managers may have experienced this already if they imposed decisions onto their staff.

The COVID-19 crisis is transforming work and how it is done, not just in universities. If managers think that they unilaterally know how and what to do, they could turn disorder into chaos.

###

Authors:

Johanna Weststar, Associate Professor of Labour and Employment Relations, DAN Department of Management & Organizational Studies, Western University

Carolyn Troup, Research Fellow, Centre for Work, Organisation and Wellbeing, Griffith University

David Peetz, Professor of Employment Relations, Centre for Work, Organisation and Wellbeing, Griffith University

Ioana Ramia, Research fellow, evaluation, UNSW

Sean O’Brady, Assistant Professor, labour relations, McMaster University

Shalene Werth, Senior lecturer, management, University of Southern Queensland

Shelagh Campbell, Associate professor, ethics and labour relations, University of Regina

Susan Ressia, Lecturer, employee relations, Griffith University

Disclosure statement: David Peetz organised funding for this research by securing a contribution from each of the Australian universities involved. However, as they’re not named or glorified in this article, they don’t especially benefit from publication of this article.

Carolyn Troup, Ioana Ramia, Johanna Weststar, Sean O’Brady, Shalene Werth, Shelagh Campbell, and Susan Ressia do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.